Researchers in the US have discovered a new form of carbon produced by “activating” expanded graphite oxide. The material is full of tiny nanometre-sized pores and contains highly curved atom-thick walls throughout its 3D structure. The team has also found that the material performs exceptionally well as an electrode material for supercapacitors, allowing such energy-storage devices to be used in a wider range of applications.

Capacitors are devices that store electric charge on two conducting surfaces separated by an insulating gap – the larger the surface area of the capacitor, the greater its capacity to hold charge. Charging a capacitor requires electrical energy, which is recovered when the device is discharged. Supercapacitors, also known as electric double-layer capacitors or electrochemical capacitors, store more charge thanks to the double layer formed at an electrolyte–electrode interface when a voltage is applied. Although already used in applications such as mobile phones, these devices are currently limited by their relatively low energy storage density compared with batteries.

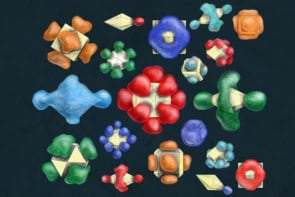

Now, Rodney Ruoff and colleagues at the University of Texas at Austin and scientists at the Brookhaven National Laboratory, the University of Texas at Dallas and QuantaChrome Instruments have synthesized a new form of porous carbon with a very high surface area. The carbon consists of a continuous 3D porous network with single-atom-thick walls, with a significant fraction being “negative curvature carbon” similar to inside-out buckyballs. The researchers used the material to make a two-electrode supercapacitor with high gravimetric densities of capacitance, energy capacity and power per unit mass. What is more, the team claims that the process used to make this form of carbon can be scaled up to produce industrial quantities of the material.

Expanded with microwaves

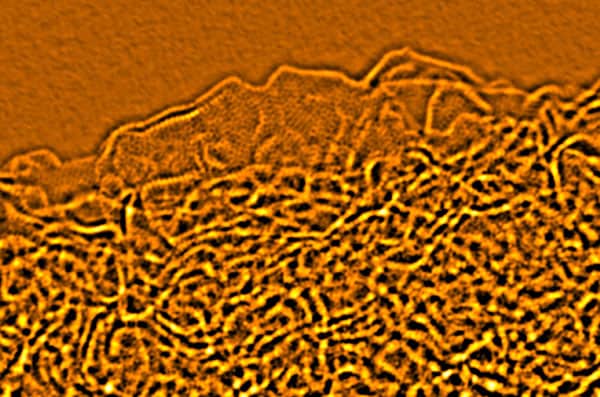

Ruoff and co-workers begin by converting samples of graphite into graphite oxide, which they expand using microwaves to generate what they have dubbed “microwave-expanded graphite oxide” (MEGO). The MEGO is then treated with potassium hydroxide so that its surface is covered (or decorated) with the chemical. After heating at 800 °C for about an hour in an inert gas, “activated MEGO” or aMEGO is obtained.

“What is quite surprising is that the [potassium hydroxide] remarkably restructures the carbon so that a 3D porous structure is generated with essentially no edge atoms,” Ruoff told physicsworld.com. “Every wall in the structure is one atom thick and all the carbon atoms there are sp2-bonded.”

The researchers used aMEGO as the carbon for electrodes in a supercapacitor – mixing it with different electrolytes. They obtained “exceptional” gravimetric energy densities that are about four times higher than that of state-of-the-art conventional supercapacitors, for example those based on porous activated carbon, on the market today.

Best BET

The porous carbon produced also has a “BET” (Brunauer–Emmett&nadash;Teller) surface area of up to 3100 m2/g. For comparison, typical activated-carbon materials have BET surface areas in the range of 1000 to 2000 m2

And that is not all: the material is also very stable and continues to work at 97% capacitance even after 10,000 constant current charge/discharge cycles.

“The Texas work shows an important increase in energy capacity on a gravimetric basis, but unfortunately the graphene material has relatively low density. It will be interesting to see if further work yields higher-density materials with corresponding improvements in volumetric energy density,” says John Miller of the capacitor maker JME and Case Western Reserve University, who was not involved in the research.

Ruoff and colleagues are optimistic and now plan to further improve the new carbon and hope to obtain further funding so that they can carry on conducting more fundamental research on generating still better materials based on similar types of structures. “We also hope to optimize performance in other electrical energy-storage systems in parallel,” reveals Ruoff.

The work is reported in Science.