The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen from roughly 280 ppm shortly before the industrial revolution to about 390 ppm today. Now researchers in the US have done atom-level simulations that suggest that increased concentrations of the gas causes ice to become more brittle, and so more likely to break up or crack. Although the work focussed on tiny “nanocrystals” of ice, the team believes that it could improve our understanding of cracking in much larger structures such as glaciers and ice caps.

“This result suggests that the chemical composition of the atmosphere can be critical to mediating the motion and/or melting of large volumes of ice, beyond the effect of global temperature,” Markus Buehler of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) explains. “In some sense the fracture of ice due to carbon dioxide is similar to the breakdown of materials due to corrosion, e.g. the structure of a car, building or power plant where chemical agents ‘gnaw’ at the materials, which slowly deteriorate. In the case of ice, carbon dioxide can play the role of a corroding agent and lead to a destabilization of the structure.”

Glaciers and ice caps cover 7% of the Earth, an area greater than Europe and North America. They reflect 80–90% of incoming solar radiation and act as a carbon sink – this means that significant melting could create a feedback loop and boost warming further.

Breaking bonds

“Similarly to other materials, the fracture process of bulk ice, for example glaciers, is usually initiated by single cracks propagating in ice crystals by breaking the hydrogen bonds between water molecules,” says Buehler. “These cracks eventually grow and break down the entire glacier by propagating and branching over large distances. Very large-scale ice fractures occurred recently close to Pine Island Glacier [in Antarctica], which generated an iceberg with an area the same size as the city of Berlin.”

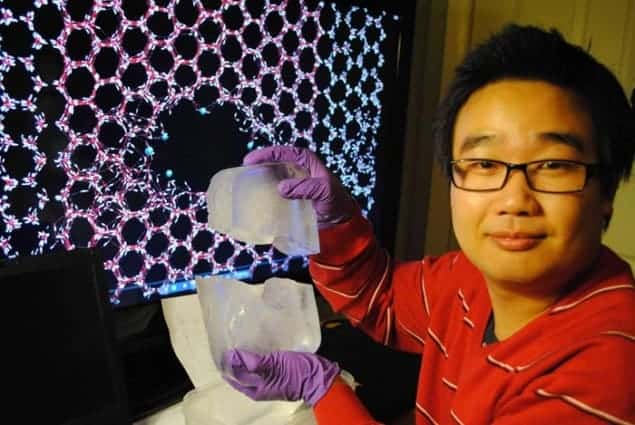

Buehler and colleague Zhao Qin used atomic simulations to examine the effect of carbon dioxide on crack growth in ice. They calculated that ice containing 2% carbon dioxide was less strong than pure ice and 38% less tough, with a fracture toughness of 12.0 kPam1/2 rather than 19.4 kPam1/2.

“It is difficult for experiments alone to directly measure the nanoscale properties of ice as a function of carbon-dioxide concentration,” says Buehler. “That is why we decided to use a series of first-principles-based atomistic-level computer simulations to investigate the very detailed mechanisms.”

Molecules move towards crack tip

The team found that carbon dioxide disrupts the hydrogen bonds between water molecules in the ice, since the oxygen atoms in the gas have a partial negative-charge and are attracted to the positively charged hydrogen atoms of the water. In the simulations, carbon-dioxide molecules attached to the crack surface and moved towards the crack tip, breaking hydrogen bonds between water molecules as they went.

“If ice caps and glaciers were to continue to crack and break into pieces, the surface area that is exposed to air would be significantly increased, which could lead to accelerated melting and much reduced coverage area on the Earth,” says Buehler. “The consequences of these changes remain to be explored by the experts, but they might contribute to changes of the global climate.”

Buehler says that the technique used in the study has also been applied to study the mechanical properties of protein materials and polymers, whose structures are typically stabilized by hydrogen bonds. “For these structures, we found that the chemical conditions, for example, pH, ion concentration and ion type, are very important in affecting the material structures and mechanical functions,” he says. “Our current result, which shows that carbon dioxide decreases the hydrogen-bond strength at the crack tip, agrees with the findings from our former work but makes an important contribution to the understanding of one of the most critical, and abundant, materials for our planet’s climate – frozen water, or ice.”

Buehler and Qin report their work in Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. They say that more work is needed to link their microscopic insight to larger-scale properties of ice, glaciers and other geologically relevant structures.