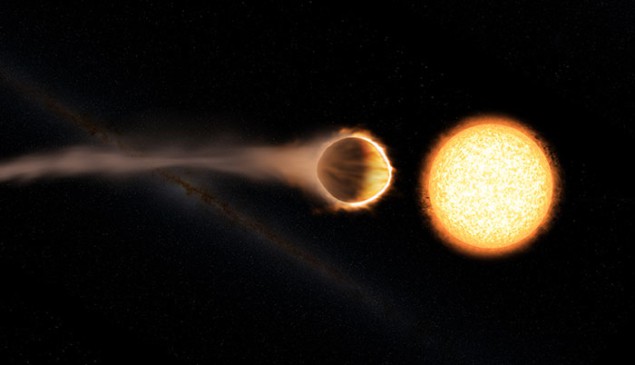

The strongest evidence to date for an exoplanet stratosphere has been identified by scientists using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Spectra of WASP-121b’s atmosphere are the first to show the resolved signature of hot-water molecules for a planet outside the solar system.

A planet’s stratosphere is a layer of atmosphere where temperatures increase with altitude. For example, Earth’s stratosphere contains ozone gas that traps ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, raising the temperature within the layer. Meanwhile, on Jupiter and Saturn’s moon, Titan, methane is behind the temperature increase.

Boiling metal

WASP-121b is a “hot Jupiter” – a gas giant with 1.2 times the mass of Jupiter and 1.9 times the radius and a much higher temperature. Located about 900 light-years away, it orbits the star WASP-121 in just 1.3 days, and the planet’s close proximity to the star means the top of its atmosphere reaches 2500 °C – so hot that some metals can boil.

While previous research has found possible signs of stratospheres on other exoplanets, the evidence of water on WASP-121b is the best to date. Thomas Evans from the University of Exeter in the UK and colleagues identified the water because it has a very distinct and predictable interaction with light, depending on its temperature. If there is cool water at the top of the atmosphere, the molecules will prevent certain wavelengths of light (typically infrared due to heating) from escaping the planet. On the other hand, if the water is hot, the molecules will “glow” at the same infrared wavelength. “When we pointed Hubble at WASP-121b,” says Evans, “we saw glowing water molecules, implying that the planet has a strong stratosphere.”

Unknown gaseous cause

The temperature change within stratospheres of solar-system planets is typically around 56 °C, but on WASP-121b the temperature rises by 560 °C. The researchers do not know what chemicals are causing this rise in temperature, but possible candidates include vanadium oxide and titanium oxide because they are gaseous under such high temperatures and are commonly seen in brown-dwarf stars, which have similarities to some exoplanets.

“This result is exciting because it shows that a common trait of most of the atmospheres in our solar system – a warm stratosphere – also can be found in exoplanet atmospheres,” says team member Mark Marley at NASA’s Ames Research Center in the US. “We can now compare processes in exoplanet atmospheres with the same processes that happen under different sets of conditions in our own solar system.”

The work is presented in Nature.