A technique to create multi-coloured 3D images that can share space with physical objects has been developed by researchers in the US. The work is at an early stage, but it offers several potential advantages over currently available techniques for creating 3D images such as holography.

The technology used by the android R2D2 to project the 3D video footage of Princess Leia pleading “Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi: you’re my only hope” into thin air was never explained in the film Star Wars. Scientists, however, have invented several technologies capable of producing the impression of 3D images. The best known, and most widely used is holography, in which a 2D surface sends light to the eye in such a way that the brain reconstructs this light as having come from a 3D object. Unfortunately, this optical illusion only works for a fairly narrow range of viewing angles: “Holograms and displays like them are based on 2D modulating surfaces that have to be looked at like a TV screen,” explains Daniel Smalley of Brigham Young University in Utah, “You always have to be looking into the screen to see it.”

In a volumetric display, however, the light originates from where your eye sees the image. Such displays have several advantages over holograms. As the image does not rely on an optical illusion, for example, it is unaffected by the viewing angle. “You can be lying flat on the ground and you can see what’s coming up out of the display,” says Smalley. Furthermore, it is (at least in principle) possible to wrap the image around the viewer or another physical object.

Electric blue

Unfortunately, although several technologies for volumetric displays have been developed, they have all faced severe limitations. Researchers at Keio University in Japan, for example, developed a technique in which lasers create bright plasma in the air – unfortunately, however, the colour is dictated by air’s plasma frequency: “You can have any image you want, but it’s electric blue,” says Smalley.

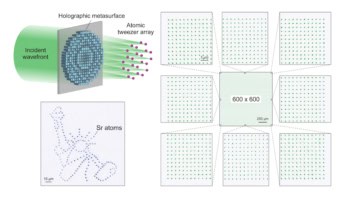

In the new research, Smalley and colleagues confine a micron-scale particle in an optical trap using the photophoretic effect. This relies on the fact that a laser can heat the medium surrounding a particle unevenly to apply radiation pressure that holds the particle in place. To trap the particle, the researchers use near-invisible 405 nm laser light (the same wavelength used in a Blu-ray laser). They then deliver red, green and blue light as required down the same optical path, and this light scatters from the particle. As the eye sees this light much more strongly, the scattered light from a particle allows the researchers to create a bright spot of any colour they choose.

By adjusting the position of the trap minimum to move the particle around while continuously scattering light from it, the researchers create simple, millimetre-scale line images in the air that do not flicker when viewed with the naked eye. The size and complexity of these images is restricted by how fast the researchers can move the particle around without it flying out of the trap. The researchers managed to produce much more detailed and larger images, including a 5 cm-tall view of the Earth from space with a resolution of 1600 dpi. This was done by collecting light emitted over several tens of seconds. The researchers suggest that more complex images could be produced in real time by trapping and scattering light from multiple particles simultaneously so that, for example, each particle only had to be swept in one plane or along one line.

Challenges remain

Barry Blundell of the University of Derby in the UK is cautiously impressed: “Volumetric displays have been researched for more than 100 years,” he says. “You see a lot of cyclic research – so people pick up an idea, research it for a few years, it falls by the wayside, and ten years later somebody else picks up the same idea. What these researchers have done is a quite new approach to the implementation of a volumetric display.” He cautions, however, that, much remains to be done: “You’ve got a long way to go before you can take an image that you can create in 40 s and bring it down into one you can create in 1/30 s so that you can incorporate animation,” he says.

The technology is described in Nature.