This year’s Nobel prize is welcome recognition for cosmology

Back in the 1960s, according to Paul Davies’ new book The Goldilocks Enigma (see “Seeking anthropic answers”), cynics used to quip that there is “speculation, speculation squared – and cosmology”. Anyone trying to understand the origin and fate of the universe was, in other words, dealing with questions that were simply impractical – or even impossible – to answer. But that has all changed with the development of new telescopes, satellites and data-processing techniques – to the extent that cosmology is now generally viewed as a perfectly acceptable branch of science.

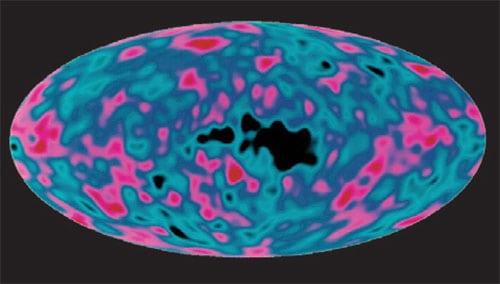

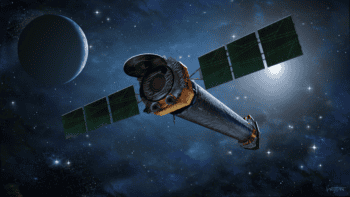

If anyone was in any doubt of cosmology’s new status, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences last month gave the subject welcome recognition with the award of this year’s Nobel prize to John Mather and George Smoot (see pp6–7; print version only). The pair were the driving force behind the COBE satellite that in 1992 produced the now famous image of the cosmic microwave background. The mission’s data almost certainly proved that the universe started with a Big Bang, while tiny fluctuations in the temperature signal between different parts of the sky were shown to be the seeds of the stars and galaxies we see today. These results are regarded by many as the start of a new era of “precision cosmology”.

But for cosmologists, the job is far from over. There are still massive holes in our understanding of the cosmos, notably the nature of dark matter and dark energy, which together account for over 95% of the total universe. Indeed, some regard dark energy and matter as just ad hoc assumptions needed to fit the data. (Hypothetical particles called “axions” are one possible contender for dark matter (see pp20–23; print version only), but don’t bet your house on it.) Some physicists even think it makes more sense to adjust Newtonian gravity rather than invoke dark matter. But the notion that cosmology is in crisis, as argued by some on the fringes of the subject, is almost certainly wide of the mark. For the moment at least, we should celebrate Mather and Smoot’s success.