Russia’s apparent willingness to pull out of the International Space Station after 2024 is throwing up questions about the future of astronauts in low-Earth orbit, as Peter Gwynne discovers

The future of astronauts in low-Earth orbit remains unclear following Russia’s decision to withdraw from the International Space Station (ISS) after 2024. The move was announced in late July by Yuri Borisov, who replaced Dmitry Rogozin as head of the Russian space agency Roscosmos earlier that month. Russia’s withdrawal will end a two-decade collaboration on the ISS, although Borisov promised that the country would “fulfil all [existing] obligations to our partners” before its partnership ends.

The timing of Borisov’s announcement was surprising given that in early July, NASA and Roscosmos had announced “seat swaps” for astronauts and cosmonauts to fly in the other nation’s spacecraft. As things stand, Russia and NASA’s other partners in the ISS – Canada, Japan and the European Space Agency (ESA) – are contracted to use the station until 2024. But as of now, Russia has not officially informed NASA of any decision to leave the space station. “NASA has not been aware of decisions from any of the partners, though we are continuing to build future capabilities to assure our major presence in low-Earth orbit,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement in late July. “NASA is committed to the safe operation of the ISS through 2030 and is co-ordinating with partners.”

It is very, very difficult to imagine a future where ISS can operate without the partners working together

Laura Forczyk

Roscosmos’s decision is assumed to be in response to Western criticism of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Roscosmos delayed the launch of several satellites aboard one of its Soyuz rockets from the ESA spaceport in French Guiana after ESA recognized sanctions against Russia in February. Yet general relations among astronauts and cosmonauts on the ISS and between Russian and US space administrators have been mostly cordial. “A lot of trust had built up for a lot of years,” former NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine told Physics World. The issue now is whether the US and partners could potentially operate the ISS until 2030 if Russia does pull out.

Future prospects

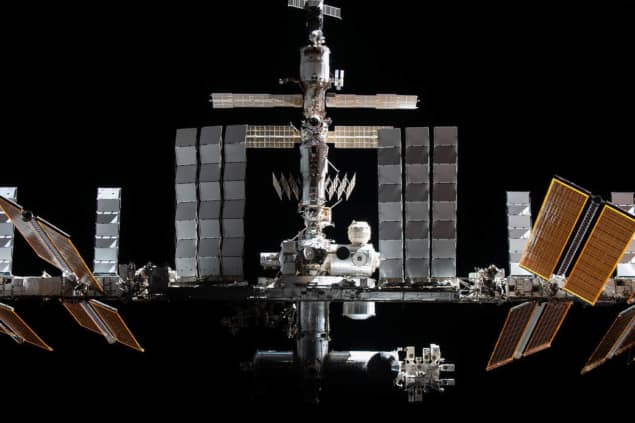

The ISS was first occupied by astronauts on 2 November 2000. Since then, modules have been added and astronauts have conducted space walks and studied phenomena ranging from the growth of protein crystals to human muscle atrophy in microgravity. According to Kathryn Leuders, NASA’s associate administrator of human space exploration and operations mission directorate, such research has produced about 400 scientific papers including 185 in the past two years.

As the two key partners in the venture, the US and Russia individually operate the station’s two main segments. The US supplies the structure’s electrical power and Russia the propulsion capability that maintains it in orbit. “The two sections are so interconnected and rely on each other such that it is very, very difficult to imagine a future where ISS can operate without the partners working together,” Laura Forczyk, founder and executive director of space consulting firm Astralytical, told US National Public Radio.

Physically separating the ISS’s two segments would be extremely difficult. And without Russia, NASA would face the issue of how to overcome the station’s tendency to lose height in its orbit. Space analysts see at least a few approaches. NASA could possibly control the orbital boosts directly from Houston rather than Moscow. It might use US or rented Russian spacecraft to nudge the structure higher. More complex would be designing an entirely new propulsion system.

End-of-life plans

Scott Pace, director of George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute, says that Russia’s announcement “is not really a surprise” given today’s less friendly atmosphere. “It’s not particularly productive to react to every statement, but to focus on the facts,” he adds. “We should probably have some back-up thoughts on maintaining the station, but [also] to think of what we do after the ISS ends – it’s not whether but when and how.”

Whatever happens in the next few years, the ISS is now nearing the end of its life. Leading up to 2030, NASA plans to lower the station’s orbit slowly, before allowing it to crash into an uninhabited area of the Southern Pacific Ocean in 2031. Analysts see no likelihood of a successor on the same scale as the football-pitch-sized ISS in the future. “It’s a beautiful thing, but we’re looking at smaller, more specialized stations,” Pace adds. “The future is probably multiple smaller human-tended stations rather than the large assembly.”

NASA has already started to encourage that type of technology. Last year, the agency awarded contracts to three groups to build commercial space stations: Blue Origin, partnering with Sierra Space; Nanoracks, in partnership with Lockheed Martin; and Northrop Grumman. In addition, Axiom Space is developing what it calls “the world’s first commercial space station”. Axiom has announced plans to launch the first component of its station by 2024. However, none of the companies has indicated when they expect astronauts to occupy and run their stations. China embarks on a decade of human space exploration

The US is also not alone in building the next wave of low-Earth orbit space stations. China, which has been kept out of the ISS collaboration, is expanding its own operational and occupied Tiangong space station, which launched in April 2021. Roscosmos has talked about a launch in 2028 for its first new space station module, although some have expressed scepticism about

that date.

Mariel Borowitz, a specialist in international space policy at the University of Georgia, says that whatever happens in the future, it is unlikely to involve the US and Russia collaborating again. “Russia is partnering with China, not the US, in Moon exploration – all that happened prior to the invasion of Ukraine.”