The International Year of Astronomy marks the 400th anniversary of the first use of an astronomical telescope by Galileo Galilei. As the 2009 celebrations kick off, Edwin Cartlidge explains how one of Galileo’s telescopes is being rebuilt by researchers in Italy, while Michael Banks looks at some of the events taking place this year

Of the many achievements of Galileo Galilei, among the most famous is a series of astronomical observations that he started in 1609 and announced in March 1610 in a publication entitled Sidereus Nuncius (“Starry Messenger”). These included radical new views of the Moon and the stars, as well as the discovery of four satellites orbiting Jupiter. By removing a major doubt about the heliocentric model — namely that the Earth appeared at the centre of things because only it had a satellite — the observation of the Jovian moons led to a new view of the universe and in the process brought Galileo considerable fame.

What had made these observations possible was the telescope. Invented in the Netherlands in 1608 (although there have been claims that it was first built a few years earlier), the telescope was initially seen as a useful new aid to warfare. However, once news of the device spread south, Galileo was able to use his considerable skills as an instrument maker to multiply the magnifying power of the basic spyglass so that he could use it as an astronomical tool.

Now, staff at the Institute and Museum of the History of Science in Florence, Italy, together with the Arcetri Observatory, also in Florence, have built a replica of one of Galileo’s telescopes and are using it to generate the images that, to the best of their estimations, Galileo himself would have seen. The aim, explains museum curator Giorgio Strano, is to understand exactly what Galileo observed and how he made his observations. “We are trying to distinguish precisely between what Galileo was potentially able to see ‘objectively’ with the telescope and what was, instead, the product of physiological, psychological and cultural factors,” he says.

The Moon, Saturn and beyond

The telescope being built by the Florence team is not actually a replica of the one used by Galileo to make the observations he reported in Sidereus Nuncius. It is likely, instead, that these results were obtained using a telescope with a magnification of about 30. What the team is building is an exact replica of the device that Galileo gave to his patron the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo II, in about 1610. The 93 cm long instrument consists of two lenses — a converging one, the objective, and a diverging one, the eyepiece — that can magnify distant objects by up to a factor of about 20. Whereas this more modest instrument has survived intact, sadly the only part that remains of the more powerful device is the objective lens, making it impossible to remake.

Reproducing Cosimo II’s telescope has involved a painstaking investigation of the original lenses — with the National Institute of Applied Optics in Florence having measured their shape and refractive index, and the National Institute of Nuclear Physics in Florence using X-ray fluorescence to determine the composition of the glass. The Arcetri Observatory, on the other hand, built a mechanical structure to house the lenses and regulate the distance between them. This structure was then linked up to a charge coupled device of 2300 × 3400 pixels, which transforms incoming photons to electrical signals and thereby generates digital versions of the images that would form on the retina of a human eye placed behind the telescope. The plan is to make these images accessible online.

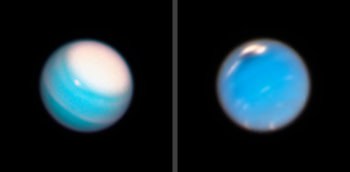

Astronomers at the Arcetri Observatory are now using this apparatus to image all the objects recorded in Sidereus Nuncius and in other works by Galileo. The Moon and Saturn have already been observed, and these observations have demonstrated the effects of chromatic aberration in Galileo’s instrument. The focal length of a lens depends on the wavelength of light passing through it, so in practice it is impossible to bring white light to a precise focus, and this defocusing can be seen in the images of Saturn and of the Moon.

Arcetri Observatory director Francesco Palla says that he and his colleagues are now obtaining images of Jupiter’s moons and the phases of Venus, which provided another crucial piece of evidence in favour of the heliocentric hypothesis (with the Ptolemaic alternative incorrectly maintaining that we would never see more than half of the surface of Venus illuminated by sunlight). The researchers are also observing the Pleiades and Orion star fields, which Galileo found had scores of stars in addition to the few already known at that time. Sunspots permitting, observations will also be made of the changing face of the Sun — a hammer blow against the idea of the immutability of the heavens when originally revealed by Galileo.

The Galilean eye

Michele Camerota, a historian of science at the University of Cagliari in Italy, believes that the observing project will provide a valuable source of new data on the performance of Galileo’s telescopes and that it will permit an “extremely faithful” reconstruction of what Galileo saw. However, performing these observations has proved tricky. Aside from having to work with a very limited field of view (Galileo’s combination of convex objective and concave eyepiece producing a field of view of about one quarter of a degree), the researchers in Florence have also struggled to find somewhere dark enough to observe Jupiter — Arcetri nowadays being swamped by light from the city.

Having eventually found a suitable location in the hills beyond the city, Palla and colleagues then had to introduce what he describes as an “inevitable trick” in order to observe the Jovian moons. Because the moons reflect so little sunlight, their imaging requires an exposure of several seconds, during which time they move appreciably across the sky. The telescope therefore needs to be placed on a rotating mount in order to track the moons — a problem that Galileo would not have encountered because the eye can make do with less light than a CCD needs.

However, even when all of the imaging has been completed, the project will not be over. That is because to work out what Galileo saw it is not enough to simply find out what kind of images his telescope created. The researchers also want to work out what Galileo’s eye would have done with those images. And for that, they need access to his body. “We know that Galileo died blind, so he must have had visual problems,” says Paolo Galluzzi, director of the Florence museum. “We want to look at his DNA to try and work out what these problems were.”

Galluzzi does not yet have permission to open Galileo’s tomb, which lies in the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Florence, because the basilica’s rector opposes such a move. But Galluzzi is determined to keep trying. “Building the replica telescope and acquiring the digital images are the first two parts of the project,” he says. “Understanding the physiology of Galileo’s eye is the third part. If we can achieve this, then we will be in a position to really understand how Galileo viewed the universe.”

IYA2009: a taste of things to come

January marks the start of the International Year of Astronomy (IYA2009) as designated by the United Nations, and endorsed by UNESCO — its body responsible for education, science and culture. IYA2009 is intended to mark the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s first use of the telescope for astronomical observations. The aim of the initiative is to generate interest in astronomy and science, especially in young people, under the central theme of “The universe, yours to discover”. IYA2009 is a global celebration of astronomy with more than 100 countries involved in preparing activities. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) and UNESCO are coordinating events throughout the year, which are happening regionally, nationally and internationally. National events can be found at the IYA2009 individual country websites. Although this list is not exhaustive, here is a sample of what is coming up around the world during the year. Meanwhile, Physics World will be publishing a special astronomy issue in March, and there will be additional astronomy coverage on physicsworld.com throughout 2009.

Cosmic diary

All year round, worldwide

www.iya2009.org

Professional astronomers around the world will be blogging about their day to day activities and what it is like to be an astronomer. Researchers from NASA, the European Space Agency and the European Southern Observatory will be blogging as part of this project

Portal to the universe

All year round, worldwide

www.portaltotheuniverse.org

A website built for IYA2009 will feature rolling news, new images taken by telescopes, blogs by astronomers, and videos, as well as links to other astronomy websites. It will also contain a directory of observatories, facilities and astronomical societies.

IYA2009 opening ceremony

15–16 January, UNESCO Headquarters, Paris

Hundreds of people are expected to attend the official launch, such as government ministers and Nobel-prize winners, including Robert Wilson, who shared one half of the 1978 prize with Arno Penzias for the discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation. There will be exhibitions as well as talks by leading figures in astronomy.

Conference on the role of astronomy in society and culture

19–23 January, UNESCO Headquarters, Paris

Examining the relationship that astronomy has established with different cultures around the world. There will also be an accompanying art exhibition.

GLOBE at night

16–28 March, worldwide

This project lets students, teachers and parents take part in a global campaign to observe and record the magnitude of visible stars to measure light pollution in a given location. After the observations are collected, a map will be produced showing the levels of light pollution around the world.

100 hours of astronomy

2–5 April, worldwide

One of the cornerstone projects of IYA2009, this event will try to make as many people as possible use a telescope and look up the stars.

International Astronomy Day

2 May, worldwide

Local astronomical societies, planetariums, museums and observatories will be giving presentations and workshops to help increase public awareness about astronomy.

IAU general assembly

3–14 August, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Leading astronomers will head to Brazil for a two-week conference to discuss everything from dark matter and galaxy clusters to whether the fundamental constants change with time.

Kepler’s heritage in the space age

24–27 August, Prague, Czech Republic

Celebrating the 400th anniversary of the publication of Johannes Kepler’s 1609 book Astronomia Nova, in which he provided the formulation of the first two laws of planetary motion in the solar system. The conference at the National Technical Museum in Prague celebrates Kepler’s contribution to astronomy.

Astronomy and its instruments before and after Galileo

28 September – 3 October, Venice, Italy

The conference will examine at how astronomical instruments have changed with time and the differences between countries when exploring the universe.

Great worldwide star count

9–23 October, worldwide

This event encourages everyone to go outside, look skywards after dark, count the stars they see in certain constellations, and then report their findings online.

European Society for Astronomy in Culture (SEAC) conference

25–31 October, Alexandria, Egypt

The SEAC, which includes archaeologists, historians and astronomers as its members, will meet to discuss the practice, use and meaning of astronomy in culture.