A House of Representatives spending bill plans to scrap the James Webb Space Telescope. Garth Illingworth looks to a gloomy future for astronomy and astrophysics if that happens

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) – the planned successor to the Hubble Space Telescope – is in serious trouble. The most powerful body in the US House of Representatives – the Appropriations Committee – has adopted legislation that would specifically terminate the JWST, as part of a drastic reduction of NASA’s 2012 budget by $1.9bn to $16.8bn. The cancellation is not expected to be included in the US Senate’s separate spending bill, which is to be released this month. However, the negotiations for a compromise bill between the House and the Senate would entail substantial risk for the JWST under “normal” circumstances. In the current political climate, the risks are even greater – early autumn will be a critical time for the JWST.

Hubble is arguably the most widely recognized scientific mission of all time, delivering thousands of images of the cosmos. The JWST will be immensely more productive and powerful than Hubble via its much larger primary mirror and its hugely advanced technology. The JWST will continue the tradition of NASA’s “great observatories” – Hubble, the Chandra X-ray observatory and the Spitzer infrared telescope – by shedding light on the first galaxies and stars, as well as studying exoplanets for evidence of water and other molecules related to life. No existing or planned telescope, on the ground or in space, could do the amazing science that the JWST would do.

Lost generation

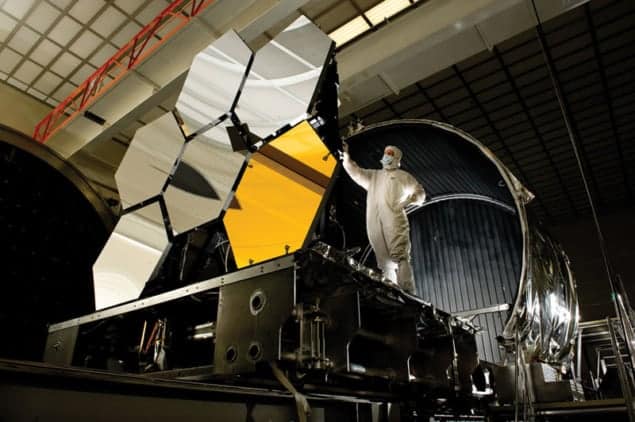

So far, $3.5bn has already been spent on the JWST, with excellent technical progress being made. Roughly 75% of the hardware for the mission has been delivered or is in the final fabrication stage. Indeed, in June polishing of the JWST’s 18 beryllium mirrors was complete and their cryogenic performance is now being tested. The mirrors are so smooth that if each were the size of the US, the typical surface ripples would be just 5 cm high. Unfortunately, all this good news has not percolated as widely as it should have to government, and we are now in the invidious situation of possibly losing the most powerful observatory ever conceived. In doing so we would not only harm US astronomy but also seriously damage our collaborations with Europe and Canada, which have already spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the JWST programme.

The cancellation would spell a dangerous time for US science. The ability of NASA and the wider science community to establish and sell “flagship” missions to Congress would be seriously hampered in future. Given that the JWST was first proposed 22 years ago, it is likely that US astronomy would not recover for at least a decade or two, effectively losing a generation of scientific progress.

Management issues

The JWST took its first major step in 2000, when it was included as the top-ranked space-based mission in the “decadal survey” – where astronomers in the US identify the highest priority research activities in astronomy and astrophysics for the coming decade. The mission’s initial cost of around $1bn was, however, underestimated and substantial efforts were made to put the JWST on a firmer fiscal footing in the early 2000s. Then in 2005 US President George W Bush (and Congress) placed further stress on NASA’s budget by requiring that the space agency do “everything” with no additional funding. This included continuing with the space shuttle for five more years, replacing it with a new rocket capability, finishing the International Space Station and planning for missions to the Moon and Mars. Following the adoption of Bush’s plan, the science budget was cut, losing roughly $10bn since 2005. It was then very hard for spending on JWST to be ramped up in its most critical funding years.

Budgetary stress, however, was not the only issue. Progress of the JWST was hit by poor oversight and lack of independent validation, together with communication and leadership issues at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the Science Mission Directorate. Following concerns about schedule delays and cost overruns, the Independent Comprehensive Review Panel (ICRP) was set up in June 2010 to look into NASA’s management of the telescope.

Chaired by John Casani from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the ICRP concluded that while the JWST project had made considerable technical progress that was “commendable and often excellent”, there were concerns that NASA was not exercising adequate independent oversight and evaluation of project performance (see “Hubble successor hit by budget setback”). NASA has since implemented virtually all of the ICRP’s 22 recommendations and has released its revised plans for the JWST’s completion, setting a possible 2018 launch. However, the full cost of the mission has not been announced, although some estimates put it in the range $7–8bn, which is consistent with extrapolating the ICRP’s estimate of $6.5bn if the JWST was launched in late 2015.

The answer to why the JWST has problems is simple. Any and every project that involves new technology and is on the scale of the JWST will have difficulties. This is not bridge-building – nobody has made a telescope like the JWST before. If the JWST did not have problems, it would mean that we lacked ambition and were not utilizing our full technological potential. What must be done is to plan for resolving and fixing problems quickly. In my view, it is impossible to carry out a one-off project of this scale, with such challenging technologies, without adequate funding and substantial contingency to minimize the inevitable problems. The core issue for the JWST is that it did not have the contingency needed to address such problems immediately.

Counting the costs

If the House of Representatives’ budget for NASA becomes law and the JWST is cancelled, I would compare the damage to astronomy to that the high-energy physics community suffered in the early 1990s when the Superconducting Super Collider was canned. There would be a similar devastating change in scientific opportunities, but with a very important difference – no other nation (or group of nations) could currently build a JWST. There is no plan B for the JWST as US particle physicists had with CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. China and Europe could build a replacement for the JWST in the coming decades, but only far into the future.

Cancellation would also mean that more than a third of the long-term astronomy budget would disappear overnight. The full expectation and understanding has been that as the JWST is completed, its funding would revert to the astrophysics budget and be available for new missions. But with no JWST, those funds would not be available. The recommendations of the 2010 decadal survey could not be implemented, meaning no Wide-Field Infrared Space Telescope, no International X-ray Observatory, no Laser Interferometer Space Antenna and no significant post-Kepler exoplanet mission. Astrophysics would become one of the smaller programmes in NASA space science, similar to what heliophysics is now. Study of the entire universe would receive similar funding to that of one star – the Sun.

Once Hubble and Chandra die by end of the decade, US space-based astronomy would consist of a series of small missions. This would be a devastating retreat from where we are now, and certainly from where we would be with the JWST. Astronomy research would lose more than $30m per year of funding for research students and postdocs at institutions across the US. While small missions have done great science, and will do so in the future, they are narrowly focused, infrequent and have a narrow research support base. They are far from being “observatories” that can respond quickly to new scientific issues and involve a broad swath of the international science community and its students and postdocs. If we are to continue the remarkable productivity and iconic visibility of NASA’s great missions such as Hubble, Chandra and Spitzer, then we must continue with the JWST. Scientists, and the public, need to have their voices heard if astronomy is to remain as dynamic and exciting as it is today. Amazing discoveries await when the JWST flies.