The total lunar eclipse that took place last Sunday night/Monday morning has become a dramatic demonstration of the power of citizen science. As millions of people across Europe, western Africa, and North and South America watched the start of totality, a meteorite hit the moon, producing a tiny flash of light on the darkened lunar surface.

It is the first known meteorite strike to have taken place during a lunar eclipse.

The story begins in the United States with the extremely sharp-eyed Reddit user Ahecht. “I saw a bright flash on the moon opposite the remaining sunlit sliver,” he wrote. “I ran inside and checked the timeanddate webcast from Morocco and it was visible there too, so it wasn’t an airplane or something else local. It was also visible on the Griffith Observatory webcast. Could this have been a meteor impact on the moon?”

The news quickly spread. “Wow,” tweeted the UK-based astronomer and science writer Will Gater. “I’ve just checked in Photoshop & the flashes from the 2 different feeds are in *exactly* the same location. Given there was *also* a visual observation I’d bet good money this was indeed a meteoroid impact on the Moon.”

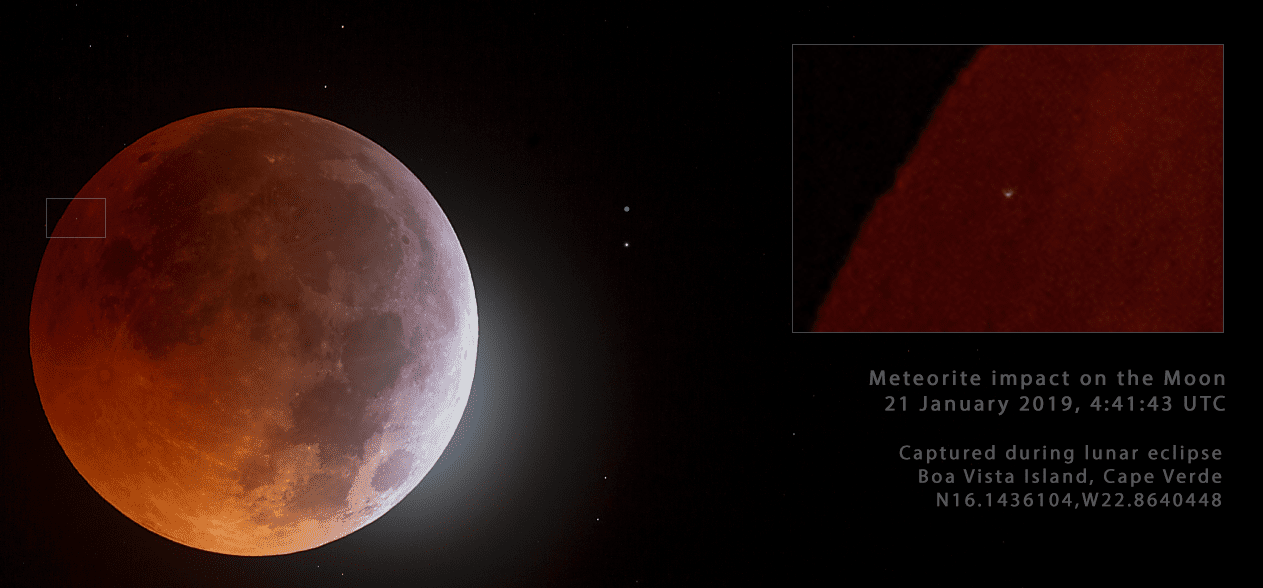

Live coverage of the eclipse published by timeandate.com (see below) shows the impact as a tiny flash of light at 04:41:43 UTC, about one hour and twenty minutes into the video. It appears on the left edge of the moon, just below the 10 o’clock position.

These live pictures were provided by Steffen Thorsen, the chief executive of timeanddate.com, who was filming the eclipse from Ouarzazate in Morocco. (Alas, the commentator who is speaking at the moment of impact — and who completely misses the historic occasion — was me. In my defence, it is very difficult to spot; you might have to replay the video a couple of times to see it.)

Confirmation of the strike came the day after the eclipse. The Moon Impacts Detection and Analysis System (MIDAS) is a robotic system that has been specifically designed to record the flashes produced by meteorites hitting the moon. The system, which has been running since 1997, uses telescopes at three astronomical observatories in Spain: Sevilla, La Hita and La Sagra. The day after the eclipse, José María Madiedo of the University of Huelva reported that MIDAS had observed the lunar flash, as shown in the image.

The citizen science part of the story is continuing, with astrophotographers and other observers checking to see if they were lucky enough to record the impact. Petr Horálek was in the Cape Verde Islands for the eclipse. When he was inspecting his images for hot pixels and other imperfections, he found one “very weird” dot that could have been a star.

“But it was in front of the moon,” he says. Later, when he read about the meteorite, he realized he had taken his picture right at the moment of impact. “What a lucky shot!” he admits.

Meteorite strikes such as this one can help us to learn more about the interplanetary matter in our solar system. “This is a great opportunity for shared science,” says Noah Petro, a planetary geologist with NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) mission. “I’m asking to archive your data, let’s try to co-ordinate.”

If any Physics World readers have images or observational reports to share, Petro would like to hear from you. You can find his contact details here.