Tim Berners-Lee predicts the future of online publishing in an article he wrote for Physics World in June 1992. This article was republished in March 2019 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the World Wide Web. Links and images have been added that did not appear in the original print-only version

Will editors of journals and magazines such as this be out looking for new jobs in a few years’ time? Will a world overrun with forests use paper only for packing the confectionery eaten by hungry hackers? Should you save this issue of Physics World as a possible collector’s item?

Experience with computer networks, and in particular with the “World-Wide Web” (“W3”) global information initiative (see box “The World-Wide Web”), suggests that the whole mechanism of academic research will change with new technology. But when we try (dangerously) to envisage the shape of things to come, it seems that some old institutions may resurface, albeit in a new form.

The change from paper to electronic form is, perhaps most significantly, a change of timing. It will take the same amount of time to read a page of text, but to follow up a reference will take a few seconds rather than a few days. It will take the same amount of time to compose an article, but to search a library catalogue will take a few seconds rather than a few hours (including the trip to the library). The change in timing will affect the whole way we do work.

Picture a scenario in which any note I write on my computer I can “publish” just by giving it a name. In that note I can make references to any other article anywhere in the world in such a way that when reading my note you can click with your mouse and bring the referenced article up on your screen. Suppose, moreover, that everyone has this capability.

The World-Wide Web

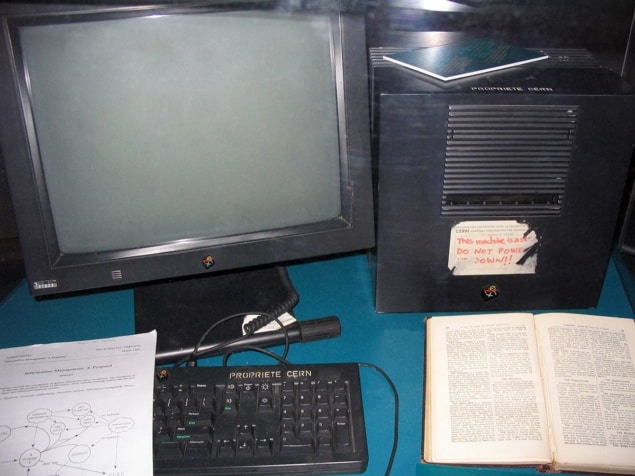

The World-Wide Web (more easily pronounced as “W3”) is an initiative to allow any information on the networks to be easily shared by non-specialists. W3 was conceived at CERN as an essential infrastructure for the particle physics community, but its application has spread into many disciplines.

Technically, W3 uses hypertext (see box “What is ‘hypertext’ anyway?”), text retrieval and wide-area networking techniques. The user runs a browser programme on his/her local machine: this programme hides all the technical details, network connections, data format and protocols. The web is completely distributed: anyone can “publish” data and make links to other documents.

To the user, W3 gives a simple consistent point-and-click or command line interface to a vast wealth of information. Servers exist at several particle physics institutes, and we encourage new institutes to join the web.

All information about W3 is of course available by browsing the web, but questions may be mailed to: www-bug@info.cern.ch (or from JANET, www-bug@ch.cern.info).Those on Internet who wish to try it out in its simplest form can telnet info.cern.ch (no username/password). Better, pick up a browser by anonymous FTP from info.cern.ch.

These are the assumptions of “global hypertext” (see box “What is ‘hypertext’ anyway?”) and it is generally supposed that this will lead to a tangled web of interconnected jottings representing the sum of human knowledge. By selectively following links passed to me by friends, I can rapidly find anything I want to know. Modelling the real world with all its random associations, the “web” allows me to replace a day’s worth of library visits, discussions over coffee and rummaging in filing cabinets with a dozen or so clicks with the mouse.

Before readers jump in and take this to pieces, let me assure the cynical that to a certain extent, this exists, and where it exists, it works. The W3 initiative at CERN and various other institutes has, along with a few similar projects, put together the infrastructure of network protocols and common software. It seems to be taking off, to judge from the readership of our own “server” doubling every other month and new servers cropping up increasingly frequently. Even without global authorship, global readership of data provided by the few has been spectacularly successful. Almost all the data on the web are a window onto some other source, so it is not hand-crafted hypertext, but it’s in demand nevertheless.

In this happy anarchy, two problems arise. One is that of collective schizophrenia. The bulk of human understanding may well develop two independent pockets of knowledge about the same thing. This can happen on a small scale, when one writes a document with the sinking feeling that one has written it before but can’t find it. It can happen on a global scale when researchers on different continents investigate the same phenomenon, unaware of each other.

To solve this, some global co-ordination is clearly required. However, centralised co-ordination is out of the question for an estimated 1014 documents. A number of people have started to make lists of resources on the network and have generally been swamped by its growth. The most spectacular success is the “archie” project which keeps a mammoth index of the names of almost all the files available in the internet archives worldwide. Even Peter Deutch, its Canadian instigator, admits that network information is likely to grow faster than his disks, and that his indexes will have to become specialised.

My own attempt to edit a hypertext encyclopaedia, in which pointers to network information sources are classified by subject, leaves me overwhelmed even now. As I looked around for people to help, I realised that I was looking for specialists in particular fields to look after them – like specialised librarians.

What is 'hypertext' anyway?

The term “hypertext” was coined by Ted Nelson, something of a guru in this field, in the 1950s, but only recently has wide-area hypertext become a reality, by allowing one to follow references (“links”) at will.

Typically, one clicks with a mouse on a highlighted phrase, and another related document is displayed. Hypertext is both a new medium for writing, and also a convenient way of representing existing multiply connected information.

The bringing together of the provider of information and the enquirer, the “resource discovery” problem, is up for grabs in the networking community. Solutions, however, always centre on some idea of “subject”. The keyword list, or vocabulary profile, of a document is used to route it to some specialised index which will note it, and direct enquirers to it. Whether you take the Dewey decimal system or the English language as a basis, there need to be centres of knowledge on particular subjects. So, at CERN, we keep pointers to information at other high-energy physics sites. I’d like to see more of this. I’d like someone to maintain an eminently readable hypertext overview of the field, with links to more detailed discussions of specific areas, and eventually to the work of particular groups and individuals. I am not sure whether I would call the result an encyclopaedia, or a journal, or a library. The job-title “cybrarian” has been suggested. However, I can tell you from experience that it takes an incredible amount of time. The tasks of librarians and reviewers are not going to be usurped by academics in their spare time.

The second problem which the information web faces really started with the laser printer. Before laser printers came around, you could tell something about the reliability of an article by its feel: handwritten scrawl torn off a spiral notebook never carried quite the authority of glossy typography. Nowadays, it all looks the same, elegant Optima 10 point.

The same will be true of networked information. It is true that individuals slip into new conventions for conveying formality or lack thereof. A lower case i for the first person gives electronic mail a “hastily scribbled” impression, not to mention the conventional faces on their side (:-) of Internet news. As well as conventions, new ethics for electronic publishing are developing. However, one needs the equivalent of a refereed journal to convey authority. In the hypertext world, the actual physical distribution of data is not the issue here: it is the organisation. The feel of the paper of a document will be replaced by its registered name. A document registered under my personal authorship will not carry the same weight as one registered in the International Standards Organisation’s catalogue of standards.

I see the need for two organs: the newsletter and the encyclopaedia. An encyclopaedia will be an overall attempt by the knowledgeable, the learned societies or anyone else, to represent the state-of-the-art in their field. An encyclopaedia will be a living document, as up to date as it can be, instantly accessible at any time. It will contain carefully authored explanations and summaries of the subject, as well as computer-generated indexes of literature. A reference to a paper from the encyclopaedia conveys authority and acceptance by academic society. A measure of a paper’s standing may be conveyed by the number of links it is away from an encyclopaedia.

I see the need for two organs: the newsletter and the encyclopaedia.

Tim Berners-Lee, writing in 1992

The newsletter is a commentary on the changes in the field. A personalised newsletter can be generated automatically by looking for changes in the encyclopaedia and linked works. A user may effectively ask his computer each day, “Tell me anything new which has been linked to one of my favourite subjects”. It may be possible to generate a newsletter largely automatically, but a human being does so much better. This is especially true of the job of summarising in a review or contents page.

I say “an encyclopaedia” rather than “the encyclopaedia”. Another fundamental change will be the low start-up cost of publishing. Anyone can start a new encyclopaedia, and, if enough people refer to it, it will be widely read, and quoted by society’s established authorities. This allows for many encyclopaedias, even many parallel societies. Conventional science will have no hold on pockets of alternative ideas and, so long as innocent individuals are not misled, I see great worth in this freedom. Here we hope to see a market economy in information. The quality of an article is judged by its own contents, and by the quality of the articles to which it refers. There is therefore an incentive to refer to good articles, so the better articles will be most referred to, and most read. Authoritative sources will take care only to refer to reliable work, but deserving small journals can start and rapidly gain prestige. The many medium-size discussion groups of the Internet news system provide a vehicle for bringing new sources quickly to light and establishing acceptance.

These arguments convince me that publishing houses, far from being unnecessary, will be in for very exciting times. Their jobs and those of librarians seem to have merged into one as classifiers and reviewers of the world’s knowledge. The practical issue arises of how to pay these good people. There is something distasteful about charging by the byte. The feeling of freedom to browse is marred by a price tag on an icon, a taxi-meter ticking away on the corner of the screen. Also, it is difficult to find a general method for previewing a document so that one can see what one will get for one’s money. How can one ascertain which documents were really read, or even then were actually useful to the reader? The clear advantage of this technique, however, is that the information “market” becomes more real and more direct when real money is tied in at a low level.

Payment by subscription also has its appeal. Just as one subscribes to a journal, or gains the right to use a library, so one would subscribe to an information service – paying not for the information read but for that which is available just in case. However, the power of global hypertext to represent knowledge lies in the unconstrained way links can cross boundaries between organisations, subjects, and continents. Following a link should ideally take under a quarter of a second (so as not to disturb the train of thought). It should not be accompanied by questions about account numbers and credit ratings.

Following a link should ideally take under a quarter of a second. It should not be accompanied by questions about account numbers and credit ratings.

Tim Berners-Lee, writing in 1992

As a third possibility, the charging and the paying may be done between organisations, over negotiating tables, behind the back of the poor researcher. Let a consortium of physics institutes commission an electronic journal, give it a budget and review it from time to time, cross-licensing between societies so that, for example, members of a national physics society will be granted access to chemistry journals. Perhaps we can imagine an association of publishers which attempts to redistribute the money in a fair fashion.

The global-village pioneers

A mixture of such schemes may exist, and the market may decide which one works best. The market will be fierce, and enthusiastic amateurs will always be willing to compete where they feel a professional service falls below a certain standard.

The existing web gives a good feel for what is possible, using free information. Within high-energy physics, the web contains mainly user manuals, online help, phone books, discussion lists, announcements, news, the minutes of meetings and preprint lists. In other subjects, data range from catalogues of DNA sequences and chemical formulae, through poetry, prose and religious books to the weather forecast. Thanks to the spread of the Internet, this is available in most academic institutes. Already it shows us a more efficient way to pool our knowledge, while keeping up standards of freedom of information which academics, and the Internet, have always promoted.