For neutron scientist Peter Böni, founding a company felt like a huge gamble – until a chance meeting over coffee with like-minded colleagues persuaded him to take the plunge

What led you to start Swiss Neutronics?

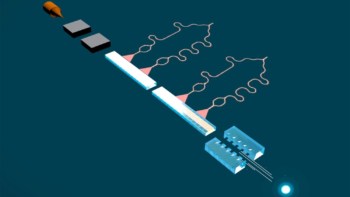

In the 1990s, I began developing so-called “supermirror” coatings, which help to transport neutrons in an efficient way from the source to the instruments. At the time, I worked as a scientist at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland, and my task was to scale this coating technology up so that we could produce many square metres of mirror for the SINQ spallation source at PSI. I was successful at this, but it was a little bit tedious to make the coatings and then watch established manufacturers of neutron guides take our products, glue them together to produce guides, and then sell them back to the PSI. At one point my supervisor, Albert Furrer, said to me, “Peter, why don’t you start a company?” but I responded “No, I’m on my own – the risk is too high.”

Then, in 1999, five of us – three scientists (including Furrer and me) and two engineers – were all sitting together during a coffee break discussing future projects at PSI involving neutron guides. I usually work quite hard and don’t take many breaks, so it really was an accident that we were all there together. Somehow, it came up that this would be a good time to start a business, and within a few weeks we had signed contracts with PSI that allowed us to use their facilities to produce the coatings and also gave us a licence to make and sell them. That was the start of Swiss Neutronics AG.

What skills did the different co-founders bring to the company?

As neutron scientists, we all knew exactly what we needed in terms of the technology, and our engineers were trained in building instruments, so they knew about the importance of making sure the supermirror technology could interface with instrumentation. Beyond that, I would say that Furrer is a very good scientist and organizer, and I had a lot of contacts with people who might be interested in our technology. But it wasn’t like you sometimes read about, where you have one innovative person with lots of knowledge who is looking for a financial officer, an engineer and somebody who does advertisements to help them start a company. We were just good friends who happened to be there drinking coffee, and we were good at speaking to each other and working together in an open way.

How did you get funding for your venture?

At that time, it was fairly easy to found a spinoff from PSI – we simply had to agree to pay a licence fee for the products we sold, and the institute was very generous in allowing us to do business from our existing offices and in permitting us to use laboratories and the facility for producing the supermirror coatings. That was great, because it meant the financial risk was very low; we just paid for our offices and machinery on a daily or hourly basis. It also helped that in the same year we founded Swiss Neutronics, I got a professorship at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), which is very open to entrepreneurship; our university president is very happy when he can tell politicians about professors and scientific personnel getting involved in founding companies. So I had an open door to work at Swiss Neutronics as my side job.

How did the business expand?

At first, we only produced coatings – we did not do anything else. But then – and this was actually before I started my professorship – I was approached by the TUM with a suggestion that we deliver approximately 50% of the neutron guides for their new neutron source, the FRM-II. At that time, we had no experience of building neutron guides, but we got some initial payments when we signed the contract for the FRM-II, and we used it to rent or buy the equipment we needed, such as a laboratory space, a machine for grinding glass and alignment tables to put together the guides. And then we were lucky, because just as the FRM-II contract ran out in 2003, we got a second large contract with the UK’s ISIS neutron source, and that helped us get other customers. In 2004 we took the next big step and bought our own sputtering plant – and, soon after, a building to put it in, because it didn’t make sense to install our new plant in a rented room. Until then, we had used the sputtering plant at PSI, but after that we had our own facilities in addition to the one at PSI and we could start developing them further.

I chair a group that operates five beam lines at FRM-II, and I can bring this knowledge into the company and vice versa. That is a big advantage

What are your plans for the future?

A few years ago, several big neutron facilities – J-PARC in Japan, the SNS in the US and Target Station 2 at ISIS – all completed upgrades at around the same time. The period after that could have been difficult for us, with not much new business, but we saw this coming and we chose to expand into other technologies, such as polarizing equipment and metrology. Now the core business is growing again because several neutron centres are upgrading their beamlines or new facilities such as the European Spallation Source are being built, so we plan to expand, but in a reasonable way. We are going to concentrate on projects that are really interesting for us, such as those that involve supermirrors with large angles of reflection. We are also going to keep developing new technologies. Some of the things we do, such as super-polishing metal substrates so that the only roughness is on an atomic scale, are driving the technology for neutron scattering more than many research centres do. And we can do this because we are involved in neutron scattering: for example, I chair a group that operates five beam lines at FRM-II, and I can bring this knowledge into the company and vice versa. That is a big advantage.

What do you know now that you wish you’d known when you started?

A better question might be, “What do you know now that you’re glad you didn’t know then?” But to be honest, I don’t know what I would have done in a different way. We have always been extremely conservative and we have always concentrated on improving our performance, but it’s also fair to say that we were very lucky. We made good decisions at the right time. We didn’t expand too quickly. We found the proper moment to leave PSI and rent our own manufacturing facility. We identified the correct moment to buy our own building. We invested in equipment at the right time. And maybe this was possible because we had extremely good technical staff members; people who were very involved in our business and flexible enough to work overtime if required. But you do need to be lucky to some degree. You cannot do business without being lucky.

Do you have any advice for someone starting their own firm?

When you start a company, the first five years are the most difficult. You should not expect to earn a lot of money in that time. So my advice is, if you can, start your company in what I call “luxury conditions”. Throughout my time at Swiss Neutronics, I have always had a position at a laboratory, university or other large-scale facility. That meant I always had an income, so I knew that I (and my family) would survive even if the company failed. So I tell my physics students that they should think about making a business out of their knowledge, but to do it alongside their main profession, at least at the start. Then, as soon as you feel you have enough customers, you may decide to give up your position at a university or at another company and become 100% involved in your own business. If you can do that, that’s what I would propose, because then not much can go wrong.