When atomic physicist Josh Silver thought of a new technology that could help billions of people in the developing world, he just had to pursue it. Louise Mayor tells the story of Silver’s invention of spectacles that can be self-adjusted to the user’s prescription

For people in the developed world, being a bit short- or long-sighted might prevent them from being a fighter pilot, but not having perfect vision is unlikely to crush their life’s ambitions. A trip to see the optician is all it takes to bring the world back into focus, and life proceeds as planned. In many parts of the developing world, however, poor sight can have much more serious consequences. There, eye-care professionals are scarce, and spectacles are rare and often prohibitively expensive. People who rely on good vision for their income, such as machinists or carpenters, may therefore find that as their sight changes with age they cannot work effectively, if at all, and a life of poverty can ensue. Poor eyesight can also affect children – if they cannot see the blackboard clearly at school, their education will be compromised and so will their career prospects.

Figures suggest that in the developed world, more than 60% of the population need and have their vision corrected. However, in rural parts of developing nations not served by optometrists, barely 5–10% of people wear glasses. Assuming that there is no significant physiological difference between people in the developed and developing worlds, the unmet global need for vision correction is about three billion people. If we accept that contact lenses and corneal refractive surgery are probably not appropriate solutions to the problem for people in developing nations, this means that three billion people need to be supplied with glasses.

But for the unspectacled and poor-sighted, help may be at hand from Josh Silver. When working as an atomic physicist at Oxford University in the 1980s, he came up with a simple but effective invention: glasses that can be self-tuned to one’s own prescription. Each lens consists of two flexible membranes filled with liquid. By adding or removing fluid to make the lens more convex or concave, the shape and thus power of each lens can be set by the wearer. But the glasses are not just simple to use, they are cheap too, costing just $19 a pair – a price that it set to fall soon. However, the real beauty of the invention is that while fitting the glasses in the presence of an optometrist is ideal, it is by no means essential. In areas of sub-Saharan Africa that are served by only one optometrist per million people, this ability to self-adjust the power of each lens is key. Silver’s invention has now been manufactured and distributed to more than 30,000 people, but his ambition is far greater: his “global vision for vision” is to try to ensure that one billion people have the glasses they need by the year 2020.

The very idea

Silver’s story started as a 10-year-old boy in East London, playing with a plate, some aluminium foil, a 10 cm-diameter ring made of phenolic resin and his mother’s red nail varnish. With this collection of household objects, the young Silver made his first variable optic device – a “membrane” mirror. He attached a circle of foil to one side of the ring and the plate to the other, using the nail varnish as glue. The plate had a hole in the middle which he blew into to change the shape and thus power of the foil mirror.

By the mid-1970s Silver had gained a degree from Oxford University and was playing with more advanced equipment, in his job there as an experimental physicist in the department of atomic and laser physics. In experiments to measure X-rays arising from atomic transitions, he used to attach thin metallized polyester film to vacuum chambers and detectors. It was important that the film was uniformly tensioned, as it formed the canvas for the X-rays being measured. Silver discovered that double-O-ring seals worked particularly well at sealing and stretching these films.

Fast-forwarding a decade to the 1980s, Silver found himself trying to answer a question posed by a colleague: could he create a variable-focus lens? Silver’s solution was to fill a lens made of two circular membranes with a liquid that could be pumped in or out to change the power of the lens. The first model had a poor surface and hence optical quality, but after a little thought, the nugget of double-O-ring know-how from the 1970s came back to Silver. He applied this knowledge to a revised design, which was much improved.

For Silver, who is short-sighted himself, this second lens was a key step towards creating variable-power glasses. He found that by looking through the new lens while changing its power, he could tune it so that he could see extremely well. Silver says that this got him thinking about “first, roughly how many people in the world need corrective eyewear, and second, whether people could use inexpensive variable-power lenses to essentially make their own corrective glasses”.

The case for adjustable spectacles

Silver continued his career in atomic physics – he went on to publish roughly 100 papers and to supervise about 30 doctoral students, mostly seeking to determine whether relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics can predict the energy levels in simple atomic systems. But all the while he found himself unable to shake off his interest in vision correction. Having estimated that three billion people in the world have an unmet need for vision correction, Silver began collaborating with colleagues at Oxford to investigate whether people could tune a variable-focus lens to their own prescription. “We undertook a long programme of research before I was confident enough to say ‘we know self-refraction for adults works reasonably well’,” he recalls. At the time, Silver’s group was alone in looking into this, but the technology has recently been tested independently by Kyla Smith and colleagues at the New England College of Optometry in the US (Optometry and Vision Science 2010 87 E176). The study endorses Silver’s invention as a feasible alternative where subjective refraction in a controlled clinical setting is not available.

Silver says that his work began in earnest in 1994 when he spoke to Björn Thylefors – at the time director of the World Health Organization’s Programme for the Prevention of Blindness. Explaining that about a billion people needed glasses in the developing world, Thylefors said that if Silver could do something about it, he should. And the more Silver learned about the consequences of uncorrected vision in developing nations, the more worthy a cause it seemed. “It’s about education, economics and quality of life,” says Silver. “If a child is short-sighted in the classroom, it’s difficult for them to take advantage of what they are being taught. We’re talking here about hundreds of millions of schoolchildren.”

It’s about education, economics and quality of life. If a child is short-sighted in the classroom, it’s difficult for them to take advantage of what they are being taught. We’re talking here about millions of schoolchildren

A study in the Shunyi district of China in 2000, for example, looked at 6134 children and found that by the age of 15, almost half (46%) were short-sighted and could benefit from prescription glasses. A short-sighted (myopic) eye cannot correct itself and external vision correction is needed in order to focus images on the retina. Hyperopic (long-sighted) eyes in children are able to correct themselves automatically to some extent, in a process called accommodation. But while a hyperopic child may not struggle to see at school, vision correction matters for them too – there is evidence that if these children do not get their vision corrected, they are more likely to develop sight problems later in life.

However, children are not the only ones affected. Most of the world’s population that are aged 45 or older develop a condition called presbyopia, which is where the lens loses its elasticity and therefore its ability to focus on near objects. It is a completely uniform symptom of aging; essentially, everyone becomes presbyopic when they get older. In sub-Saharan Africa, the onset of presbyopia appears to start earlier and can happen to people in their 30s. People who rely on near vision for their income but do not get vision correction can therefore find that the quality of their work deteriorates and, indeed, that they may have to stop working altogether. Adults are thereby excluded from productive working lives through lack of vision correction, and individuals and families can fall into a cycle of poverty.

To find out more about the practicalities of his invention being used in the field, Silver developed a robust and affordable product (see box “The invention: Adspecs”) to use in a wide study. With a successful pair of adjustable spectacles – or Adspecs – now in hand, things really took off. In 2003 Silver and his colleagues carried out a study funded by the UK government’s Department for International Development to find out how effective the Adspecs were (South African Optometrist 62 126). They looked at 213 participants, who had been selected by local agencies in Ghana, Malawi, Nepal and South Africa. Silver found that 78% of the sample could not obtain 20/20 vision without the use of glasses – but that their eyesight was transformed when they tried on Silver’s spectacles. (Someone with 20/20 vision is able to resolve lines and spaces that are an angle of one arcminute wide – one 60th of a degree.) “With the use of Adspecs, more than 80% would be able to pass a UK driving vision test,” Silver claims.

The invention: Adspecs

The lenses of these peculiar-looking spectacles are made not of glass but of two thin membranes sealed and stretched to a diameter of 42 mm and filled with silicone oil. The oil has a refractive index of 1.58 – within the 1.5–1.7 range used in glass and plastic ophthalmic lenses. The amount of liquid in each lens is controlled by turning a dial on each fluid-filled pump. The lenses can be made convex and thus more powerful by fattening them, or concave by drawing liquid out. They are able to give a remarkable prescription range from +6 D to –6 D. Power here is measured in dioptres (D), and is the inverse of the lens’ focal length in metres. Once the correct prescription has been found, the sealing valves are engaged and the pump and tubes can be removed.

The more than 30,000 pairs of these adjustable spectacles that have so far been distributed to people requiring vision correction in developing countries may have spawned an army of Harry Potter lookalikes. But to those for whom it means being able to benefit fully from their education by seeing the blackboard, or to continue working and supporting their family after deterioration of eyesight in middle age, this is a small price to pay. Josh Silver, who first thought up these adjustable spectacles and is a proponent of their use, acknowledges that the current design is “a bit clunky”, but new, more attractive devices are likely to be in production soon.

Distribution projects

To date, more than 30,000 pairs of Adspecs have been distributed globally in over 20 countries. The largest scheme so far has been headed by US Navy Marine Major Kevin White, who was in charge of a humanitarian aid programme in 2005 when he read about Silver’s glasses. Impressed with the Adspecs initiative, White arranged to meet Silver and later got approval from the US Department of Defense to buy and distribute 20,000 pairs. White has since set up Global Vision 2020, a US not-for-profit organization that is delivering corrective eyewear throughout the developing world. It has recently finished a successful project in Cameroon and currently has another ongoing in Liberia.

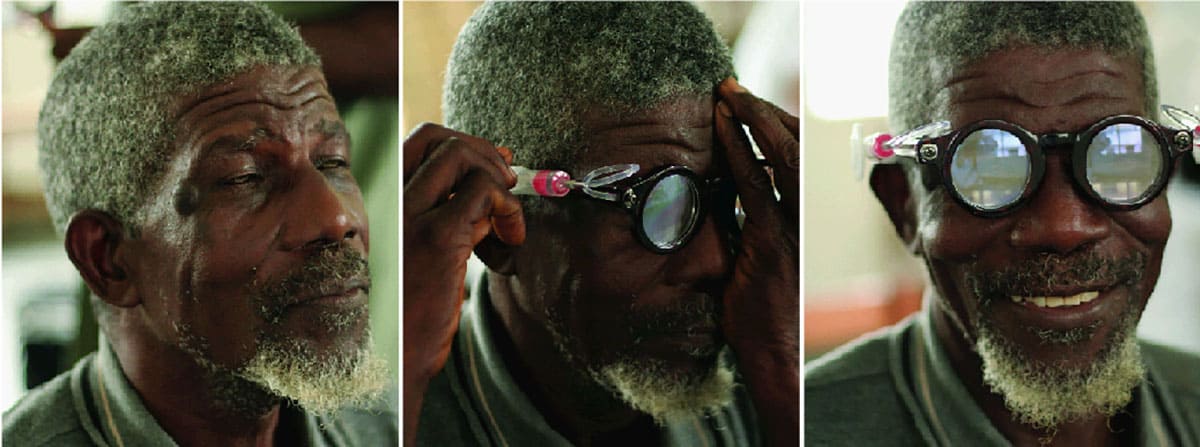

There are many inspirational stories of people whose lives have been touched by Silver’s technology. One such account from a Global Vision 2020 scheme in Kakata, Liberia, is that of father of nine Arthur Walker. As the sole head of the household, his wife having died a few years earlier, Walker supported his family through his job as a carpenter with the help of two sons. Recently one of these sons died, and with the added problem of deteriorating vision meaning that Walker was finding it harder to see his work and so could do less, he was under a lot of pressure.

Although Silver’s line of work would appear to be beyond reproach, given that it can offer people a cheap and easy way of correcting their vision, others in optometry, ophthalmology and the eyewear industry are keeping a close and sometimes critical watch on these developments. After all, the eyewear industry sells $50bn worth of products each year. But Silver stresses that adjustable spectacles will definitely not replace the need for people to see eye-care professionals who can diagnose conditions associated with eye health such as glaucoma and cataracts.Volunteers at the distribution session diagnosed Walker with both hyperopia and presbyopia. For the hyperopia, Walker fitted himself with a pair of Adspecs for close work and reading, and a pair of off-the-shelf glasses were perfect for his distance vision. Reading down the vision chart, where originally he could barely make out the second line, Walker could now see line eight and had almost 20/20 vision. Glasses in hand, Walker could return to his work with renewed vigour, and support his family where otherwise failing vision may have made this an increasingly uphill struggle.

The ideal solution would be to provide the same standards of eye care that exist in the developed world across the globe, but, in the short term at least, this is not feasible. In the UK, one optometrist cares for about 8000 people, but in sub-Saharan Africa this figure can be as high as one for every 1,000,000 people. An extra 125,000 practitioners would therefore have to be trained and retained to meet the need in this region alone. “There really ought to be a global standard for acuity,” adds Silver. “In the developed world, an optician would be expected to correct a patient’s vision to 20/20 if they are capable of this acuity. Yet globally, there appear to be no consistent standards. People in populations that are underserved cannot currently point to a standard and say ‘I want to be able to see that well.’ ”

It was to meet the need for vision correction worldwide that prompted Silver to set his target of supplying a billion people with the glasses they need by the year 2020. According to Silver, there are a number of different devices in production, but far fewer than a million are being produced in total each year. To meet his goal, 100 million pairs would need to be produced each year for next 10 years. Moreover, the cost would have to be cut by a factor of about 10 – Silver’s goal is $1 per pair.

Scaling up the Adspecs initiative will be a challenge – the investment needed to develop products is usually attracted by the promise of profits, but Silver’s aims are in essence charitable. A related concern of his is what might happen if the variable-lens technology becomes a success in the developed world. “I don’t want to see a situation where the poor in the developing world don’t get access to the technology because it is controlled by people determined to make money out of it,” he says. In fact, in 2009 Silver left a company he himself founded, which develops new self-refraction eyewear, to set up the non-profit Centre for Vision in the Developing World in Oxford.

The ability to improve the lives of thousands of people has clearly been rewarding for Silver, but that does not mean that his vision research is more rewarding than his work in atomic physics. “It’s just different,” he says. “It’s good to do research for curiosity and it’s also good to do something with an immediate technology. I encourage others to think in the same way.”

- This article first appeared in the July 2010 issue of Physics World. Since then the Centre for Vision in the Developing World has designed an upgraded set of spectacles called “New Adspecs” manufactured by Contour Optik in China. Some 500 pairs were distributed to Syrian refugees in Jordan in late 2014. Josh Silver explains more about his work in this video lecture.