Claudia de Rham and Ian Walmsley pay tribute to the contributions of the Nobel-prize winning particle theorist Abdus Salam, who founded the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, Italy, 60 years ago. They speak to Matin Durrani

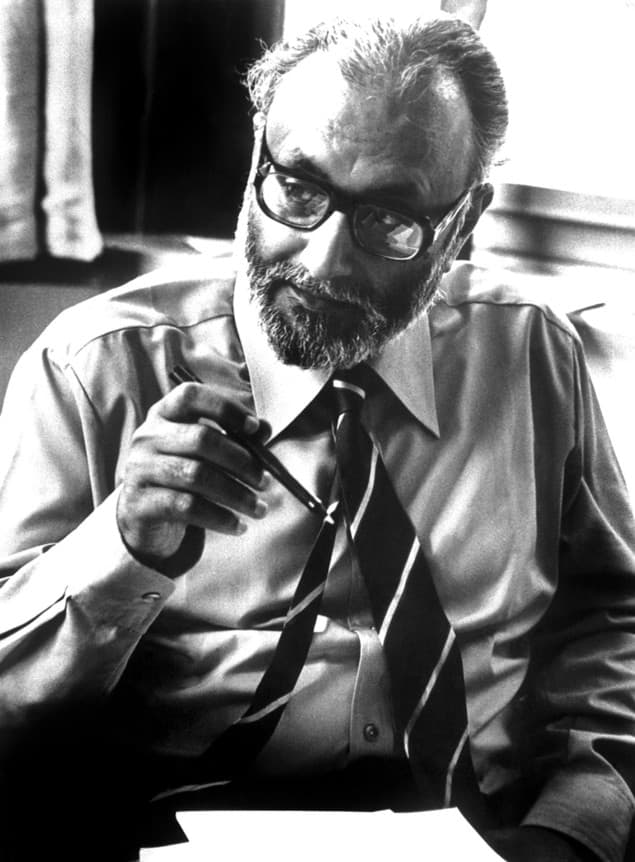

A child prodigy born in a humble village in British India on 29 January 1926, Abdus Salam became one of the world’s greatest theorists who tackled some of the most fundamental questions in physics. He shared the 1979 Nobel Prize for Physics with Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg for unifying the weak and electromagnetic interactions. In doing so, Salam became the first Muslim scholar to win a science-related Nobel prize – and is so far the only Pakistani to achieve that feat.

After moving to the UK in 1946 just before the partition of India, Salam gained a double-first in mathematics and physics from the University of Cambridge and later did a PhD there in quantum electrodynamics. Following a couple of years back home in Pakistan, Salam returned to Cambridge, before spending the bulk of his career at Imperial College, London. He died aged 70 on 21 November 1996, his later life cruelly ravaged by a neurodegenerative disease.

Yet to many people, Salam’s life and contributions to science are not so well known despite his founding of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, Italy, exactly 60 years ago. Upon joining Imperial, he also became the first academic from Asia to hold a full professorship at a UK university. Keen to put Salam in the spotlight ahead of the centenary of Salam’s birth are Claudia de Rham, a theoretical physicist at Imperial, and quantum-optics researcher Ian Walmsley, who is currently provost of the college.

De Rham and Walmsley recently appeared on the Physics World Weekly podcast. An edited version of our conversation appears below.

How would you summarize Abdus Salam’s contributions to science?

CdR: Salam was one of the founders of modern physics. He pioneered the study of symmetries and unification, which helped contribute to the formulation of the Standard Model of particle physics. In 1967 he incorporated the Higgs mechanism – co-discovered by his Imperial colleague Tom Kibble – into electroweak theory, which unifies the electromagnetic and weak forces. It changed the way we see the world by underlining the importance of symmetry and by showing how some forces – which may appear different – are actually linked.

This breakthrough led him to win the 1979 Nobel Prize for Physics with Steven Weinberg and Sheldon Glashow, making him the first – in fact, so far, the only – Nobel laureate from Pakistan. Salam was also the first person from the Islamic world to win a Nobel prize in science and the most recent person from Imperial College to do so, which makes us very proud of him.

How did his connection to Imperial College come about?

CdR: After studying at Cambridge, he went back to Pakistan but realized that the scientific, opportunities there were limited. So he returned to Cambridge for a while, before being appointed a professor of applied mathematics at Imperial in 1957. That made him the first Asian academic to hold a professorship at any UK university. He then moved to the physics department at Imperial and stayed at the college for almost 40 years – for the rest of his life.

For Salam, Imperial was his scientific home. He founded the theoretical physics group here, doing the work on quantum electromagnetics and quantum field theory that led to his Nobel prize. But he also did foundational work on renormalization, grand unification, supersymmetry and so on, making Imperial one of the world’s leading centres for fundamental physics research. Many of his students, like Michael Duff and Ray Rivers, also had an incredible impact in physics, paving the way for how we do quantum field theory today.

What was Salam like as a person?

IW: I had the privilege of meeting Salam when I was an undergraduate here in Imperial’s physics department in 1977. In the initial gathering of new students, he gave a short talk on his work and that of the theoretical physics group and the wider department. I didn’t understand much of what he said, but Salam’s presence was really important for motivating young people to think about – and take on – the hard problems and to get a sense of the kind of problems he was tackling. His enthusiasm was really fantastic for a young student like myself.

When he won the Nobel prize in 1979, I was by then a second-year student and there were a lot of big celebrations and parties in the department. There were a number of other luminaries at Imperial like Kibble, who’d made lots of important contributions. In fact, I think Salam’s group was probably the leading theoretical particle group in the UK and among the best in the world. He set it up and it was fantastic for the department to have someone of his calibre: it was a real boost.

How would you describe Salam’s approach to science?

CdR: Salam thought about science on many different levels. There wasn’t just the unification within science itself, but he saw science as a unifying force. As he showed when he set up the theoretical physics group at Imperial and, later, the ICTP in Trieste, he saw science as something that could bring people from all over the world together.

We’re used to that kind of approach today. But at the time, driving collaboration across the world was revolutionary. Salam wasn’t just an incredible scientist, but an incredible human being. He was eager to champion diversity – recognizing that it’s the best thing not just for science but for humanity too. Salam was ahead of his time in realizing the unifying power of science and being able to foster it throughout the world.

What impact has the ICTP had over the last 60 years?

CdR: The goal of the ICTP has been to combat the isolation and lack of resources that people in some parts of the world, especially the global south, were facing. It’s had a huge impact over the last 60 years and has now grown into a network of five institutions spread over four continents, all of which are devoted to advancing international collaboration and scientific expertise to the non-western world. It hosts around 6000 scientists every year, about 50% of whom are from the global south.

How well known do you think Salam is around the world?

IW: Is he well known in the physics community globally? Absolutely. I also think he is well regarded and known across the Muslim community. But is he well known to the general public as one of the UK’s greatest adopted scientists? Probably not. And I think that’s a shame because his skills as a pedagogue and his concern for people as a whole – and for science as a motivating force – are really important messages and things he really championed.

What activities has Imperial got planned for the centenary of Salam’s birth?

CdR: We want to use the centenary not only to promote and celebrate excellence in fundamental science but also to engage with people form the global south. In fact, we already had a 98th birthday celebration on campus earlier this year, where we renamed the Imperial Central Library, which is now called the Abdus Salam Library. Then there were public talks by various physicists, including the ICTP director Atisha Dabodkar and Tasneem Husain, who is Pakistan’s first female string theorist.

We also held an exhibition here on campus about many aspects of Salam’s life for school children all around London to come and visit. It’s now moved to a permanent virtual home online. And we held an essay contest for school children from Pakistan to see how Salam has inspired them, selecting a few to go online. We also had a special documentary about Salam filmed called “A unifying force”.

What impact do you think those events have had?

IW: It was really great to name a building after him, especially as it’s the library where students congregate all the time. There’s a giant display on the wall outside that describes him and has a great picture of Salam. You can see it even without entering the library, which is great because you often have families taking their children and showing them the picture and reading the narrative. It’ll spread his fame a bit more, which is really important and really lovely.

CdR: One thing that was clear in the build-up to the event in January was just how much his life story resonates with people at absolutely every level. No matter your background or whether you’re a scientist or not, I think Salam’s life awakens the scientist in all of us – he connects with people. But as the centenary of his birth draws closer, we want to build on those initiatives. Fundamental, curiosity-driven research is a way to make connections with the global south so we’re very much looking forward to an even bigger celebration for his 100th birthday in 2026.

- A full version of this interview can be heard on the 8 August 2024 episode of the Physics World Weekly podcast.

Abdus Salam: driven to success

Abdus Salam, like all geniuses, was not a straightforward character. That much is made clear in the 2018 documentary movie Salam: the First ****** Nobel Laureate directed by Anand Kamalakar and produced by Zakir Thaver and Omar Vandal. Containing interviews with Salam’s friends, family members and former colleagues, Salam is variously described as being “charismatic”, “humane”, “difficult”, “impatient”, “sensitive”, “gorgeous”, “bright”, “dismissive” and “charming”.

Despite him being the first Nobel-prize winner from Pakistan, the film also wonders why he is relatively poorly known and unrecognized in his homeland. The movie argues that this was down to his religious beliefs. Most Pakistanis are Sunnis but Salam was an Ahmadi, part of a minor Islamic movement. Opposition in Pakistan to the Ahmadis even led to its parliament declaring them non-Muslims in 1974, forbidden from professing their creed in public or even worshipping in their own mosques.

Those edicts, which led to Salam’s religious beliefs being re-awakened, also saw him effectively being ignored by Pakistan (hence the title of the movie). However, Salam was throughout his life keen to support scientists from less wealthy nations, such as his own, which is why he founded the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste in 1964.

Celebrating its 60th anniversary this year, the ICTP now has 45 permanent research staff and brings together more than 6000 leading and early-career scientists from over 150 nations to attend workshops, conferences and scientific meetings. It also has international outposts in Brazil, China, Mexico and Rwanda, as well as eight “affiliated centres” – institutes or university departments with which the ICTP has formal collaborations.

Matin Durrani