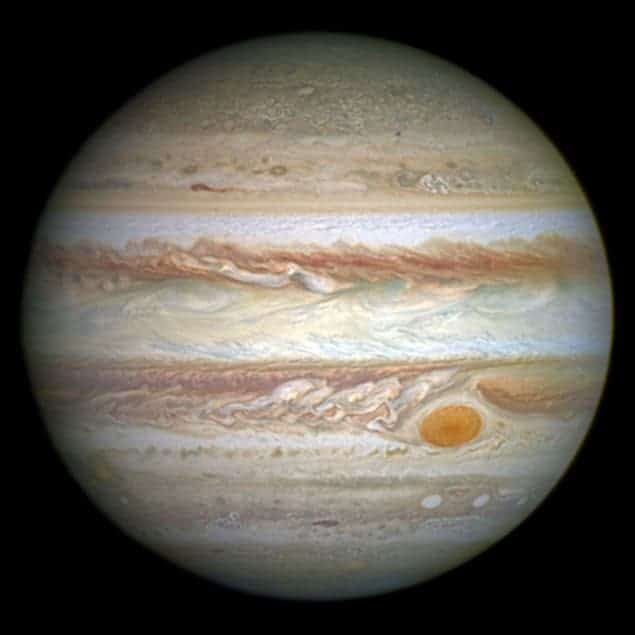

A possible refugee from the Oort Cloud that is revolving backwards around the Sun is reshaping our understanding of orbital dynamics by sharing an orbit with the giant planet Jupiter.

The object, known as 2015 BZ509 or “Bee-Zed” for short, was first spotted by the Pan-STARRS survey and followed up by a team lead by Paul Wiegert of the University of Western Ontario in Canada using the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona. If we were to look down at the solar system from above the Sun’s north pole, we would see the vast majority of objects including all the planets orbiting in a counterclockwise fashion. Bee-Zed bucks this trend: it orbits clockwise in retrograde fashion.

Although rare, retrograde orbits per se are not mysterious. What really makes Bee-Zed stand out is that it also shares Jupiter’s orbit, in a 1:–1 resonance (the minus sign indicating retrograde motion). But instead of being kicked out of the orbit by the gas giant, the asteroid is in a configuration that has allowed it to remain stable for millions of years while never colliding with Jupiter.

Shared orbit

Jupiter is no stranger to sharing its orbit. Trapped at the L4 and L5 Lagrangian points, 60° ahead and behind Jupiter, respectively, are two swarms of asteroids known as the Trojans that move prograde – in the same direction as Jupiter.

Bee-Zed is a kind of “anti-Trojan”, whose existence was predicted by Helena Morais of São Paulo State University in Brazil and Fathi Namouni of the Côte d’Azur Observatory in France, two years before its discovery. Its orbit is inclined by 163° to the plane of the ecliptic, cutting across Jupiter’s path every six years, but it never gets closer than 176 million kilometres. Jupiter’s gravity perturbs its orbit during each encounter, but “these nudges are quite gentle because the two don’t get very close,” Wiegert told physicsworld.com. Ultimately the perturbations cancel each other out, with the net result being that Bee-Zed remains on its orbital path.

Jupiter is very dominant in the solar system and can grab hold of objects and move them to new areas that can be safe or potentially hazardous

Jonathan Horner, University of Southern Queensland

Wiegert suspects that Bee-Zed was once a comet that originated from the Oort Cloud, from where comets can come from any direction, often with highly inclined and retrograde orbits. The most famous comet in history, Halley’s comet, has a retrograde orbit and is suspected to be an interloper from the Oort Cloud.

Comet puzzle

How comets like Halley transition from very long-period orbits to the relatively short periods they have today is uncertain, says Jonathan Horner of the University of Southern Queensland, Australia, who was not part of the research. If Wiegert is correct about Bee-Zed being a former Halley-like comet, then “it strikes me that this object could be part of the answer to that puzzle,” says Horner.

Another possibility is that Bee-Zed was once a member of the 6000 Trojan asteroids, but was scattered away during the early history of the solar system when Jupiter and Saturn migrated outwards and fell into a brief orbital resonance.

“It’s possible that a few objects were scattered onto retrograde orbits and were then re-captured by Jupiter as part of that migration,” says Horner. A third possibility is the Kozai mechanism, in which perturbations from outer planets can reduce the eccentricity and increase the inclination of an asteroid’s orbit to the point that its orbit flips over.

More retrograde Trojans

Wiegert suspects that Jupiter may possess more retrograde co-orbital asteroids and comets waiting to be discovered, “but there’s unlikely to be as many as the prograde Trojans simply because retrograde orbits are much rarer,” he says, adding that he “would not be surprised if we discover more of them around different planets, including Earth”.

The co-orbital resonance with Earth should prevent such asteroids from impacting our planet, but Jupiter also has a role to play in the rate of impacts on Earth. In a series of papers published between 2008 and 2010, Horner and the late Barrie Jones of the Open University found that Jupiter is just as likely to fling objects towards us as it is to sweep them up or eject them out of the solar system. The presence of retrograde co-orbitals gives Jupiter another way of capturing incoming objects, but “I don’t think it adds any credence to the idea that Jupiter is our protector,” says Horner. “Jupiter is very dominant in the solar system and can grab hold of objects and move them to new areas that can be safe or potentially hazardous.”

The discovery of Bee-Zed also raises implications for exoplanet research. Although two Jupiter-sized bodies could not be co-orbital, “it’s not unreasonable for a small planet to exist in a retrograde orbit next to a Jupiter-sized planet,” says Wiegert. Although retrograde exoplanets have previously been discovered, they are not co-orbiting with other planets; however, Wiegert suggests that it’s worth looking out for such planetary duos.

The research is described in Nature.