For the first time, astronomers have clearly observed the partial disintegration of a comet at its closest point to the Sun. Led by Man-to Hui at Macau University of Science and Technology, the international team made the observation using a combination of ground- and space-based telescopes. Describing the event as the “lingering death” of the object, the team says that its study reveals some highly unusual features in the comet’s colour and rotation.

The innermost reaches of the solar system are home to numerous comets and asteroids that reach their perihelia – their point of closest approach to the Sun – inside the orbit of Mercury. Astronomers widely predict that these objects originated from the asteroid belt – or were short-period comets such as Halley’s Comet – before being directed towards the Sun by the gravitational effects of the major planets.

Since the new orbits of these objects frequently cross paths with those of the terrestrial planets, they aren’t expected to last for more than 10 million years before colliding with a planet, or crashing into the Sun. However, the number of these objects that are currently known to astronomers is still far smaller than current models predict.

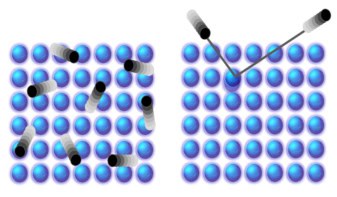

This scarcity partly stems from the difficulties involved in observing these comets, which only become bright enough to study as they approach their perihelia. As they approach the Sun, the objects are expected to disintegrate under the extreme thermal stress they experience in the Sun’s immediate proximity. So far, however, high-quality observations of this fragmentation have yet to be made.

Pioneering observations

To shed new light on the process, Hui’s team studied the comet 323P/SOHO, which has a perihelion of just around 8.4 solar radii. This comet had never been observed from the ground before, placing a large uncertainty on the exact whereabouts of its perihelion. To address this challenge, the astronomers used Japan’s Subaru telescope, located in Hawaii, whose gigantic field of view allowed them to cover a wide region of the sky in their search.

Once they had identified 323P/SOHO in Subaru’s images, the team could then study it with a combination of higher-resolution ground- and space-based telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope. Following its closest approach to the Sun, these observations revealed that 323P/SOHO developed a long, narrow tail of dust – expected for a disintegrating comet.

‘Oumuamua: visitor from another star

Hui’s team predicts that this fracturing was partly triggered by the large thermal stress experienced by 323P/SOHO. However, they also noticed an unusually rapid rotation in the comet’s nucleus. With a rotational period of just over 30 min, 323P/SOHO spins faster than any other known comet in the solar system. This rapid rotation likely accelerated its disintegration, says the team.

In total, the researchers calculated that 323P/SOHO shed between 0.1% and 10% of its total mass as it passed its perihelion. In addition, they noticed some highly unusual colours in the comet’s nucleus and tail. The colours that changed over time in ways that astronomers have never seen before. Based on their calculations of the object’s orbit and gravitational influences, Hui and colleagues now predict that it has a 99.7% chance of colliding with the Sun within the next 2000 years.

The team now hopes that the same approach will allow them to view further near-Sun comets in future studies. If the same unusual features appear in these objects, they could shed new light on the disintegration process; potentially providing new clues as to why the innermost parts of the solar system are so sparsely populated.

The observations are described in The Astronomical Journal.