Books on household science, ambitious plans for living on Mars and the most important numbers in physics, reviewed by Margaret Harris

Hot topics in domestic science

If you wanted to heat your house simply by inviting some nice warm people into it, rather than by turning on your central heating, how many of your fellow humans would you need to entice over your threshold? The answer will depend on a number of factors, including the size of your house and how toasty you like it, but in his book Atoms Under the Floorboards, author Chris Woodford reckons that, for a small terraced house, somewhere between 70 and 140 warm bodies ought to do the trick. The resulting mental image of a house stuffed to the eaves with wriggling radiator-people is just one of the many delights in this fun and accessible book, which is written for a general audience and loosely focused on the science of objects found in and around the home. This broad remit gives Woodford licence to explore a host of topics, from the physics of bicycle and car movement to the chemical make-up of the vapours given off by old plastics as they decay. (Note: taking big sniffs near old plastic dolls is best avoided unless you like the vomitous aroma of urea formaldehyde.) The marvels of modern technology also get their due, and Woodford’s discussion of communication devices is particularly interesting. If telephones were restricted to transmitting speech at the speed of sound, he observes, a single 30-sentence conversation between people in New York and Los Angeles would take around four days and nights. Woodford’s eclectic background includes a stint as an advertising copywriter, and he has a good ear for language, as when he describes shaking electrons up and down “like a jar of reluctant ketchup” to produce radio waves. The best part of the book, though, is the sense of imagination it brings to everyday phenomena.

- 2015 Bloomsbury Sigma £16.99hb 336pp

See you on Mars

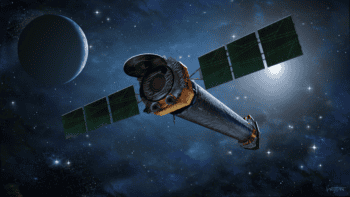

The prospect of sending humans to Mars has tantalized space aficionados for decades. Indeed, among dedicated enthusiasts, a crewed mission to the Red Planet has long since become a matter of when, rather than if. For the veteran science journalist and publisher Stephen Petranek, however, both “if” and “when” are a bit passé. In How We’ll Live on Mars, Petranek zooms straight past these quotidian questions to focus on the future – a future that will, he believes, contain Mars‑dwelling humans by 2027 and a viable colony of 50 000 settlers before the end of this century. The book is based on a talk that Petranek gave at the 2015 TED conference, and while a film of this talk is not yet available to the general public, he seems to have used the longer format to flesh out his ideas and address some audience criticisms. A keen advocate of private space exploration (particularly Elon Musk’s firm SpaceX), Petranek gives bullish answers to questions about how much a Mars craft will cost and how reliable it will be. He does, however, concede that protecting astronauts from radiation is “still a big bugaboo” and that keeping their bodies from falling apart on a long space mission remains “a significant challenge”. He also acknowledges that the history of exploration is not solely one of noble pioneers and daring adventures, noting that while “exploration may be connected to human survival…it has also led to colonization of lands already occupied, the devastation of cultures, and the plundering of resources”. Will Mars settlers end up repeating those past mistakes? Petranek isn’t sure, but at least he’s thinking about it, and his willingness to engage with tough questions adds heft to this slender but fascinating book.

- 2015 Simon & Schuster £7.99/$16.99hb 96pp

Small to large

The smallest SI-accepted prefix is yocto, denoting 10–24 of something. The largest, yotta, corresponds to 1024. In most fields of human endeavour, numbers outside the yocto-to-yotta sandpit rarely get a look-in – but physics is, of course, an exception. (Greetings, Planck’s constant, you lovely little lump of almost-nothing.) In Physics in 100 Numbers, science writer Colin Stuart ably demonstrates the discipline’s scale. The book begins with the smallest meaningful number in physics (the Planck time, 5.39 × 10–44 s) and, in a series of short, illustrated essays, races through 98 others before pitching up at the largest (1 × 10500, the number of possible configurations in the string theory landscape). It’s an impressive journey, but non‑specialist readers who begin at the beginning may find it frustrating, as the book’s structure makes it hard to comprehend just how small the first few numbers in the book really are. The classic film Powers of Ten avoided this problem by starting with familiar numbers and then zooming out and then in again; readers of Physics in 100 Numbers, in contrast, get plonked directly into the Planck scale, and are given only the sketchiest information about why these tiny distances and time intervals are important (and none at all about how their numeric values were arrived at). That’s a pity, because, within the constraints of the book’s somewhat gimmicky format (the same publishers have also produced a book called Chemistry in 100 Numbers; one suspects that biology and mathematics are also in the pipeline), there are plenty of good explanations in Stuart’s text.

- 2015 Apple Press £12.99hb 176pp