A book on debunking scientific misinformation and a guide to scientific writing, reviewed by Margaret Harris

Fighting misinformation

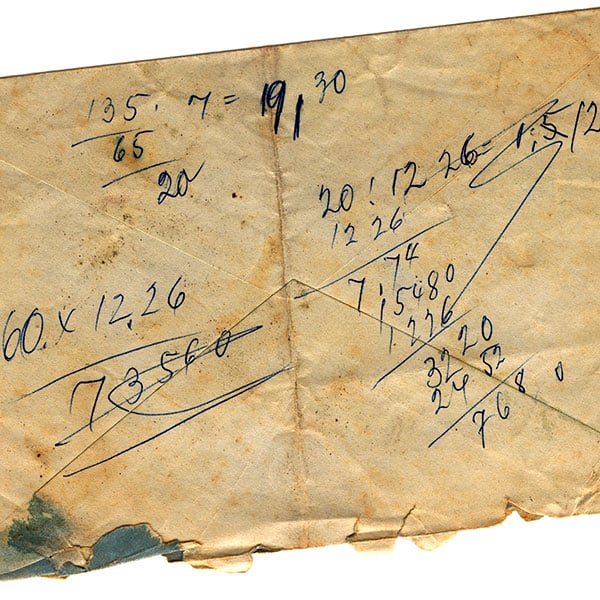

As an astronomer, educator and science advocate at Columbia University in the US, David Helfand has spent his career knocking down faulty arguments and misleading “facts” that cling on despite the huge amount of information available to modern audiences. In his book A Survival Guide to the Misinformation Age, Helfand explains how the same “habits of mind” that make someone a good scientist can also give non-scientists “an antidote to the misinformation glut”. These habits include making back-of-the-envelope estimates, and distinguishing between correlation and causation. Without such tools, Helfand writes, “you are a dependent creature, doomed to accept what the world of charlatans and hucksters, politicians and professors provides, with no way out of the miasma of misinformation”. At this point, many of Helfand’s readers will be punching the air with shouts of “Yes! I’ve been saying this for years!” And therein lies the challenge. In theory, Helfand’s book aims to convert non-experts to the scientific “cause” and teach them how to debunk misinformation. In practice, the book will probably appeal most to people who already agree with him and are perfectly capable of doing their own debunking. That does not make book worthless. Far from it: there is a long and noble tradition of using popular-science writing to encourage fellow-combatants in the fight against pseudoscience (Carl Sagan’s 1995 book The Demon-Haunted World is another example). The deeper problem is one that Helfand hints at near the end of the book, where he describes a study showing that people who reject (say) theories of evolution or climate change are not, in the main, either ignorant or lacking in scientific skills. Instead, they simply refuse to accept ideas that conflict with their pre-existing religious or political beliefs. Helfand rightly calls this conclusion “disturbing”, but he does not really engage with it. That’s unfortunate, because if this study is valid, then the premise of Helfand’s book is flawed, and he and many other defenders of science are fighting with precisely the wrong weapons. Disturbing indeed.

- 2016 Columbia University Press $29.95hb

Scientist or writer?

Stephen Heard writes about 75,000 words per year, more than many novels. But Heard is not a novelist. Instead, he’s an evolutionary ecologist at the University of New Brunswick, Canada, and he reckons his annual written output – spread across journal papers, grant proposals, peer reviews, technical reports and administrative documents – is fairly typical for a senior scientist. Since writing is such a significant part of a scientist’s working life, it’s important to do it well, and Heard’s book The Scientist’s Guide to Writing: How to Write More Easily and Effectively Throughout Your Scientific Career promises to help you do just that. The book is not a step-by-step guide to producing particular scientific documents. Instead, it focuses on topics such as building good writing behaviour; understanding the content and structure of scientific papers; developing a clear and appropriate writing style; and making the most of the revision process. Some of Heard’s tips for good scientific writing are straightforward (“an abstract is not a movie trailer and does not need to avoid plot spoilers”), while others are a bit off-the-wall (to combat procrastination, he suggests you “hang a small stuffed animal or the like near your writing station, and think of it as your writing conscience”). The most important tip, though, is one that recurs throughout the book, and can be summed up in three words: remember your reader.

- 2016 Princeton University Press £16.95/$21.95pb 320pp