Robert P Crease visits the Corning Museum of Glass in upstate New York, which claims to house the largest collection of glass art and artefacts in the world

I’m standing inside a cylindrical tower made up of hundreds of casserole dishes as if I’m surrounded by the wrap-around compound eye of a monstrously huge insect. The dishes are arranged in 17 stacked rings, each with 40 dishes (rear left of image above). Those at the bottom are clear, but as the rows go higher, I notice they grow whiter. Right at the top are all-white glass ceramic dishes of the CorningWare brand, once a staple in American kitchens.

I’ve come to the Corning Museum of Glass on the Chemung River in the beautiful Finger Lakes region of New York state. It’s a not-for-profit institution that was founded by the Corning Glass Works during the company’s centenary in 1951 and now claims to have the largest collection of glass art and artefacts in the world. Despite being several hours’ drive from the nearest cities – and further even from New York and Philadelphia – the museum is a significant tourist destination. It’s popular, even in the dead of winter.

No matter where you are, you can hear pings, clanks and chimes from an “audiokinetic” sculpture displayed in the gift store.

With glass artefacts spanning a period of 35 centuries, the museum houses items from ancient Egypt right up to breathtaking contemporary glass sculptures – such as the casserole-dish tower – as well as entries from the Netflix glass-blowing reality TV show Blown Away. The museum also contains displays on the scientific, industrial and cultural uses of glass, while demonstrations of blowing, shaping and firing glass take place almost hourly. No matter where you are, you can hear pings, clanks and chimes from an “audiokinetic” sculpture displayed in the gift store. Built by the US artist George Rhoades, it features glass balls rolling down tracks, striking bells and gongs, before bouncing off xylophones.

These days Corning Glass Works is known as Corning Incorporated – a multi-billion-dollar business that, by 2017, had produced over 1 billion kilometres of optical fibre. But the company still retains links with the museum, whose staff put me in touch with Robert Schaut. A former director of its pharmaceutical technologies division and now a Corning research fellow, Schaut explains to me via a Zoom call just why glass is such a versatile material.

Being amorphous, glass lacks a regular structure and therefore melts over a range of temperatures, as it does not have a very specific critical point. A crystal, in contrast, has a narrow melting range because the environment at every location in the material is pretty much the same thanks to its endlessly repeating unit cell. “It’s why glass softens when heated,” says Schaut, “and can solidify without ordering before you can nucleate crystalline formation.”

So what’s with the casserole tower? “It’s a visual aid,” Schaut explains, “to show the connection between temperature, cooling rate and the structure locked in the solid phase.” The transparent dishes at the bottom were reheated to a relatively low temperature – 800 °C – before being re-cooled to form an entirely crystal-free material. Higher-up dishes were fired at ever-increasing temperatures, developing nanometre-sized crystals in the glassy matrix as they cooled. The opaque, white CorningWare dishes at the very top were fired at 1100 °C, becoming 90% crystalline as they cooled, with only a small fraction of the glassy phase left.

From art to astronomy

But the Corning Museum of Glass has far more than just a tower of cooking pots. The Innovation Center, which houses the sculpture, also includes a display of glass in optical instruments, including telescopes, binoculars, periscopes and microscopes, as well as lasers and optical fibres.

Dominating proceedings, though, is a huge, 5.1 m-diameter vertical glass disc pockmarked with scars and cracks (see image left). Cast in 1934 by scientists and engineers at Corning Glass Works, it was the first attempt to make the mirror disc for the Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory in California. The disc cracked during casting, but it was completed so Corning staff could work out how to avoid the same problems when they tried again.

Elsewhere I spot a display case of glass musical instruments, including a flute and a “crystallophone” – a xylophone partly filled with water. I also see a glass harmonica, which was invented in the early 1760s by famed American statesman and scientist Benjamin Franklin. This eerie-sounding instrument has been used in Gaetano Donizetti’s opera Lucia di Lammermore in a haunting scene where the protagonist, going mad, sings what is effectively a duet with the device. It’s also been used by rock musicians, including John Sebastian of the Lovin’ Spoonful.

I spot a “crystallophone” – a xylophone partly filled with water that’s been used in Gaetano Donizetti’s opera Lucia di Lammermore and by rock musicians including John Sebastian of the Lovin’ Spoonful.

Indeed, the close links that glass has between science and art are reflected in Schaut’s own interest in the material. It began at high school where Schaut kept asking his art teacher why glass has different colours and if these can be changed. The teacher didn’t know, but suggested that staff at Alfred University, also in upstate New York, might have answers. The university is one of the few places in the US that runs courses in glass science and industry, and Schaut ended up studying ceramic science and engineering there. He then did a PhD at Penn State University on the chemical durability of glass and its interaction with the environment.

Schaut further explains that glass’s versatility is not only due to the lack of a critical point. Glass is in fact an entire family of materials, with different compositions and properties. Scientists such as Schaut are therefore able to tailor glass’s chemical durability to create, for example, glasses such as Pyrex or fused silica, which are almost inert and barely react with aqueous solutions.

In contrast, there are also highly active glasses, including “bioactive glass” – a glass used in toothpaste where it corrodes and degrades to give off calcium or phosphorus, which are useful for the human body.

In his own work, Schaut has explored and exploited more durable glasses, such as those used in vials, syringes or cartridges to store and deliver medicines. For safety reasons, pharmaceutical firms want glass vessels to have as few interactions as possible with the solution they contain. “As the pharmaceutical market kept inventing new drug formulations – and moving from large bottles that might have had 50 doses to single-dose vials or syringes – their interest shifted to tubular vials,” Schaut says. “[These have] very thin walls so their contents can be inspected for very small particles or defects that might have been introduced by the pharmaceutical handling process.”

Scientists are able to tailor glass’s chemical durability to create, for example, glasses, such as Pyrex, which are almost inert and barely react with aqueous solutions

Schaut himself helped to invent a new pharmaceutical packaging material known as Valor glass. Traditionally, drugs vials were made from borosilicate glass, which is tough but in pharmaceutical applications may flake off in ways that affect the medicines inside. Valor glass, however, has no boron, instead being chemically strengthened and having an exterior coating to make it more durable and faster to manufacture. Valor glass proved incredibly useful during the COVID-19 pandemic, with vials made from this material being used to deliver more than five billion vaccine doses. “It was interesting research,” Schaut recalls, “but we never anticipated a pandemic in which this invention would play a vital role.”

Technique matters

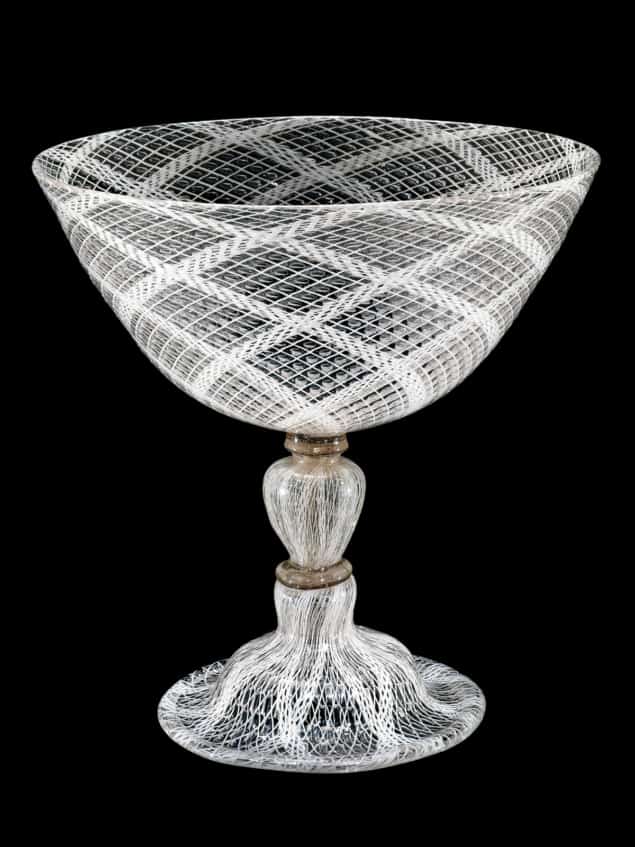

Given that Schaut came to glass science through art, I ask him to name his favourite works of art at the museum. “I appreciate technique,” he says, pointing to several examples of “reticello”. Meaning “little network” in Italian, reticello refers to a technique developed by artisans in 17th-century Venice, which was then the world’s technological and artistic capital of glassmaking. It involved creating exquisite glass vessels featuring intricate patterns of crossing lines with tiny bubbles at each intersection.

Corning’s reticello pieces, which are in a display devoted to Venetian art from the 16th and 17th centuries, form just one part of the museum’s collection of glass art. The earliest artefacts were made in Egypt in 1500 BCE, when glass was known as “stone that pours”. I see necklaces, scarabs, tools, bowls, cups and pendants – as well as a model of an ancient Egyptian glass furnace. There are also examples of Islamic glass art and African glass beads, as well as more recent items such as a hand-crafted glass car tyre by the American artist Robert Rauschenberg.

A separate collection is devoted to glass art of the 1970s, which saw an exciting new direction known as the “studio glass” movement. Drawing in part on much better, cheaper and smaller glass furnaces, artists could now involve themselves more directly in glassblowing, creating bespoke glass rather than depending on factory-made stuff. The movement was boosted by cultural exchanges between glass artists in the West and those in what was then Czechoslovakia, who were working creatively and independently under Soviet dominance. The result was a dramatic increase in the style and vibrancy of glass artworks, which the Corning museum highlights by devoting separate rooms to it. The more accessible technology also led to a wider participation of artists, with women accounting for roughly half the artists in the collection.

Another room has contemporary glass sculptures, some of which have an edgy sensibility. My eye is drawn to the spectacularly titled Cephaloproteus Riverhead (Four Hearts, Ten Brains, Blue Blood Drained Through an Alembic) by the New York-based artist Dustin Yellin (2019). It turns out to be a glass robot with tiny human figurines hanging from its nerves and glass fish swimming in its veins.

More than anything, the Corning Museum of Glass demonstrates that glass is a magical material.

One current exhibition contains pieces created in Netflix’s Blown Away, in which glass artists respond to challenges by judges, with one contestant getting eliminated per episode until a winner is announced. Contestants are helped by the museum’s “Hot Glass Demo Team” and part of the prize package is a residency at Corning. In fact, the winner of this past year’s competition – season 2 – is due to arrive two weeks after my visit. It’s a popular and memorable show. “I remember that!” exclaims a visitor behind me – a Blown Away fan – as they look over my shoulder at one piece on display.

I’m also intrigued by Va-cume! Nemesis to Oliver the Amazing by local Corning artist Cat Burns. Created in response to a Blown Away challenge to make a cartoon glass character, the piece looks like a demon attached to a vacuum cleaner bag that’s about to swallow a rug. A label says that Burns wants to express what it’s like to be mentally ill, and wishes that her work “incites her audience to discuss what it means to go a little crazy”.

Then there’s Calabash (Vessels of the Ancestors) by California artist Jason McDonald, which displays a strangely shaped glass version of the gourd. Its label says that McDonald uses glass “to make art that speaks about racism in America and the lived experience of being a working-class Black artist in a privileged, historically white medium”.

More than anything, the Corning Museum of Glass demonstrates that glass is a magical material. All the immense possibilities that it provides – from scientific instruments and industrial applications to household uses and novel forms of creative expression – stem from properties made possible by its extended phase transition. As a material, glass might not have a critical point. But that to me is its critical point.