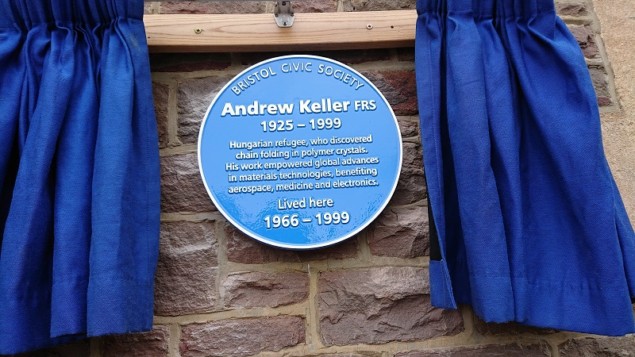

Matin Durrani attends the unveiling of a plaque to remember the Jewish refugee Andrew Keller, who escaped the Nazis and Russians before making his name in the UK

Whether dedicated to artists, scientists, sports stars or authors, I’ve seen plenty of blue plaques on houses, walls, shop fronts and labs. But until yesterday I’d never actually attended the unveiling of one of these objects – or even thought about what’s involved in creating a blue plaque and having it approved.

The plaque in question was unveiled on the former family home of Andrew Keller (1925-1999), a remarkable Hungarian-born polymer scientist who was based for most of his career at the University of Bristol in the UK. The only child of Jewish parents, Keller’s father, uncle and aunt were all sent by the Nazis during the Second World War to the Buchenwald concentration camp, never to be seen again.

As a student at the University of Budapest in 1943, Keller himself was rounded up and forced to work for a Jewish labour battalion. In what sounds like a movie plot, he escaped, hiding in a haybarn, only to be later picked up by the Russians. This time he ended up at a German-run displaced persons’ camp, but escaped again – breaking free after crawling under three rolls of barbed wire one moonless night.

It’s an incredible story of fortitude and bravery, which saw Keller return to Budapest and graduate with a degree in chemistry in 1947. But the drama was not over. With the Communists looming over Hungary, Keller fled again, escaping by the skin of his teeth the day before his PhD graduation. Thanks to family contacts in Britain and a British intelligence officer in Budapest, he managed to secure a job in the UK with ICI.

Keller moved to Bristol in 1955, where he was taken under the wing of Charles Frank, another scientist honoured with a blue plaque in Bristol. There he made his name studying how long-chain molecules line up to form very thin crystals. Weirdly, the polymers don’t lie in the plane of the crystal but at right angles to it, with Keller discovering that straight sections do repeated U-turns, or “folds”, back and forth.

You’d think that Keller’s story coupled with his scientific prowess make him a sure-fire candidate for a blue plaque. And sure enough, once the idea was raised, a group of researchers – including materials scientist Alan Windle from the University of Cambridge and Bristol physicist Bob Evans – swiftly secured approval from members of the blue-plaques panel of Bristol Civic Society, chaired by Gordon Young.

Agreeing on a form of words on a plaque isn’t easy though. “Wording is crucial,” Young told the 50 or so people who attended the unveiling in Bristol yesterday. “It has to be both vigorously expressive and yet concise.” He said that one of the city’s blue plaques required 224 e-mails before the text was agreed, but admitted that on this occasion things had been “a little bit more straightforward”.

Following a tribute by Windle, who worked with Keller and spoke of his humanity, fortitude and scientific passion, the plaque was then formally unveiled by Bristol’s deputy Lord Mayor. But it was Windle’s words that resonated with me.

Keller, Windle said, had three guiding principles for research. Always read the original literature – don’t just quote it but go back through it because it’s amazing what you can find. Second, don’t simply make measurements but use all your senses, something especially true for chemists. And perhaps most importantly, don’t be afraid to challenge the status quo.

Coming from a refugee scientist who used his wits and bravery to escape both the Communists and Nazis, those are guiding principles that it’s well worth remembering – and following.