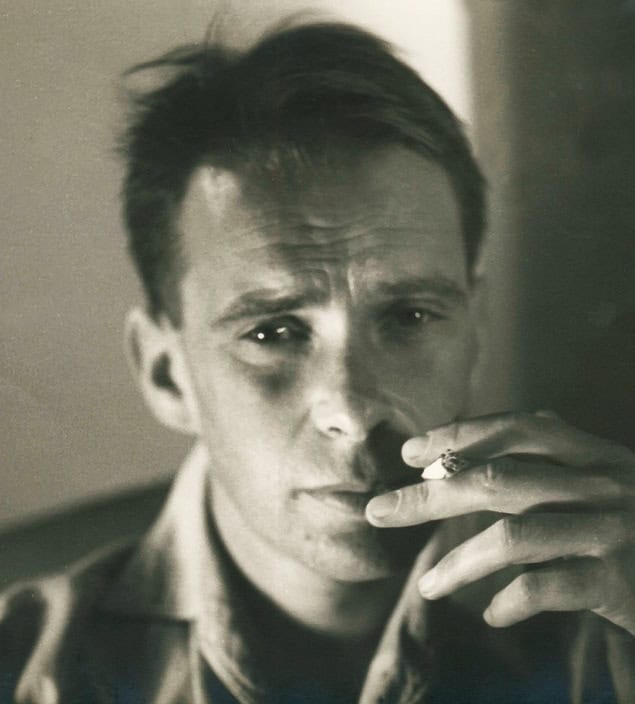

Bruno Touschek was an Austrian-born theoretical physicist who proposed what became the world’s first circular particle collider. But as Giulia Pancheri describes, few colleagues were aware of a dark past, which saw him work on a “death-ray” device for the Nazi military

One sunny day in May 1966, I entered the grounds of the Frascati National Laboratory near Rome for the first time. I had just graduated with a degree in physics from the University of Rome and had a fellowship to work in Frascati’s theoretical-physics group. It was led by Bruno Touschek, who six years earlier had famously proposed building a new kind of particle accelerator that was to become a prototype for many future devices around the world.

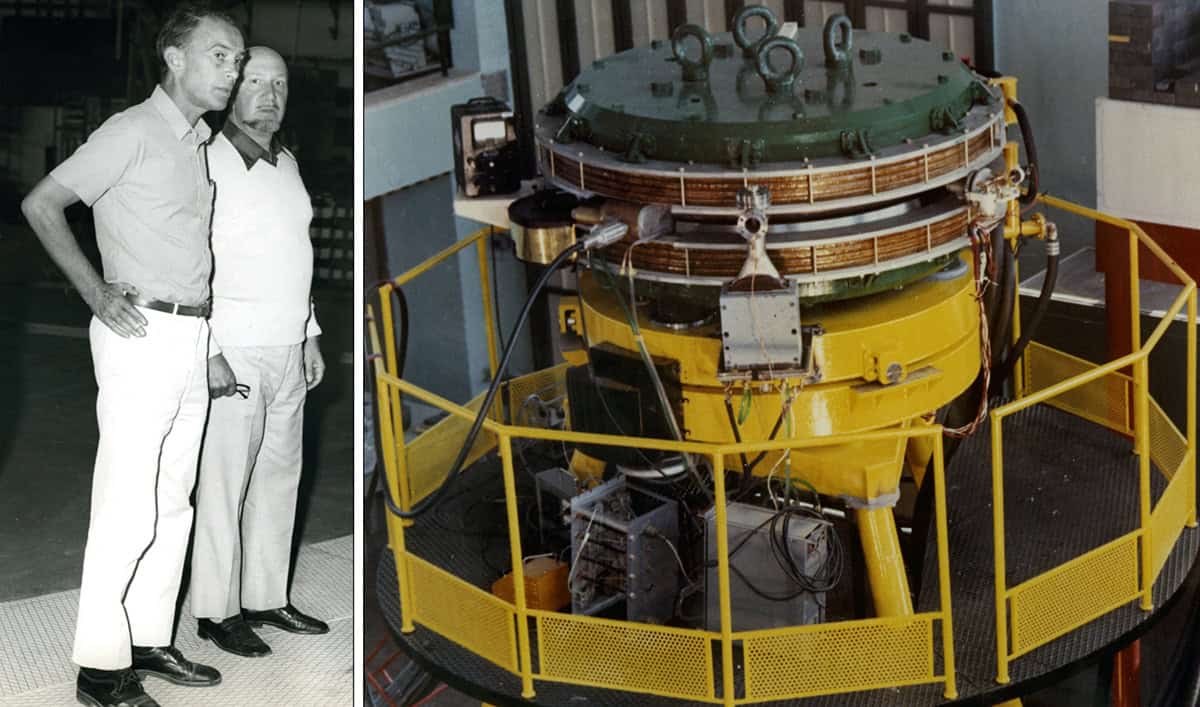

His idea did not involve smashing particles into fixed targets or colliding electrons with each other. Instead, Touschek wanted to show you could store enough antimatter in the form of positrons and collide them head-on with electrons in a circular device, with the resulting annihilation revealing new secrets of the particle world. His dream became reality in 1963 when the Anello di Accumulazione (AdA), or “storage ring”, came online.

AdA was such an extraordinary accomplishment that similar electron–positron colliders were soon built elsewhere too. Now, in 1966, Touschek was overseeing construction of ADONE – an even more powerful and beautiful machine – that would collide electrons and positrons with a centre-of-mass energy higher than any other accelerator in the world. I can still remember the emotion I felt when Touschek took me to a large hall, in a round building across the Via Enrico Fermi, where an enormous crane was putting ADONE’s first magnets into position.

Neither I – nor most of his colleagues at the University of Rome – were aware of Bruno Touschek’s dark and dramatic past

I was to spend the next year working in Touschek’s research group but neither I – nor most of his colleagues at the University of Rome – were aware of his dark and dramatic past. To most students, the Austrian-born Touschek was best known for the wonderfully clear lectures he gave on statistical mechanics, which he delivered carefully and precisely, using delightful turns of phrase and in a beautiful, neat script.

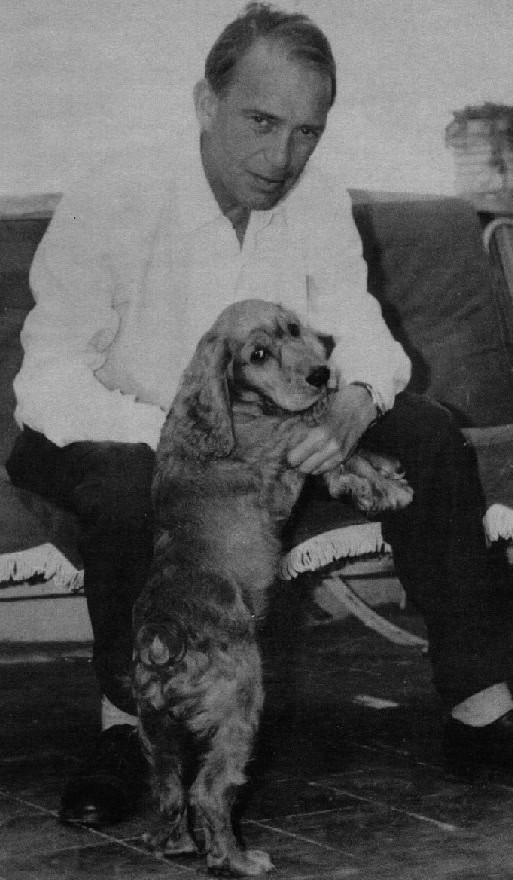

For me and many others, Touschek was a genius. Totally confident in his abilities as a physicist, he wasn’t arrogant but didn’t suffer fools gladly and liked his students to be smart and hard working. There was an aura about him that he richly deserved, having brought the AdA storage ring to fruition. The true story about Touschek’s turbulent early life only emerged years later, following his death in 1978.

I was shocked when I heard the news. It soon emerged that Touschek’s death, at the age of 57, had been caused by liver failure brought on by many years of excessive drinking. His addiction issues were well known to those around him, but it was not something that any of us really questioned. The reasons for them had only started to surface in the months before his death as Touschek began to open up about his early life to his friend and mentor, the physicist Edoardo Amaldi.

In the years that followed, much more was to come to light from his friends and colleagues, who spoke out in various articles, books, lectures and video documentaries. But the fullest story of his remarkable life only emerged in 2009 after the historian Luisa Bonolis and I came across a cache of letters that Touschek had written to his father (see “Bruno Touschek’s family letters” box).

Bruno Touschek’s family letters

In the spring of 2009, the science historian Luisa Bonolis and I visited Bruno Touschek’s widow, Elspeth Yonge, who lived in a small villa perched in the hills outside Rome. Bonolis knew from an earlier visit that Touschek had written many letters to his father and asked if we could see them. Yonge came back with a large cardboard box. Amongst various photographs and yellowed newspaper cuttings, was a folder of thin typewritten letters.

The letters, which are currently in the possession of the Touschek family, are written in German and had been carefully dated and collected by Bruno’s father. Passed back to Bruno after his father’s death in 1971, these letters describe Bruno’s years in Germany in gripping detail, including his role in the betatron “death-ray” project, his imprisonment and escape from death in 1945.

Not yet published in full, the letters formed the basis of my book Bruno Touschek’s Extraordinary Journey: From Death Rays to Antimatter (2022 Springer) and the contents of this Physics World article. Bonolis, who is currently based at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, Germany, has also written a paper with a full list of references to many of the articles, books, videos and lectures about Touschek’s life (arxiv:2111.00625).

The shocking truth was that despite being Jewish, Touschek had been made to work for the Nazis during the Second World War. Commandeered to help build a scientific device that could emit military-grade “death-rays”, his was an incredible story that is described in detail in my book Bruno Touschek’s Extraordinary Journey (Springer 2022). Touschek, who was later imprisoned and sent to a concentration camp, displayed immense courage under the worst of circumstances. Despite those traumas, he was to make vital fundamental contributions to particle physics, which he carried out with determination and vision.

Tragic times

Born on 3 February 1921 in Vienna, Touschek was the only son of the Jewish artist Camilla Weltmann and Franz Xaver Touschek – a Catholic officer in the Austrian army who had fought in Italy during the First World War. It was to be a childhood marred by tragedy. His mother died from the after-effects of “Spanish flu” when he was nine and then, in 1934, his maternal uncle killed himself following Hitler’s rise to power.

Life worsened when Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in early 1938. Touschek was a pupil at the prestigious Piaristengymnasium school and was due to take his final exams the following year. Although his mother had converted to Catholicism to marry Bruno’s father, Touschek was regarded as a Jew and forbidden from sitting the exams with his fellow students. He had to switch to the Schottengymnasium – a private, Catholic school – where he passed his exams in February 1939.

With Europe heading towards war, Touschek now decided to go to Rome, where his maternal aunt Ada lived. There he attended a course on mathematical physics at the University of Rome, which was the first sign of his growing interest in theoretical physics. But Touschek’s time in the Italian capital was spent with “more enthusiasm than profit”, as Amaldi later wrote in a 1981 CERN report, The Bruno Touschek legacy.

Discouraged from continuing to study in Italy by the antisemitic racial laws enforced by Mussolini, Touschek instead applied to do chemistry at the University of Manchester in the UK. The reason for switching subjects isn’t clear but Touschek was probably drawn by the fact that Chaim Weizmann – later Israel’s first president – had been a lecturer in Manchester’s chemistry department. The city also had a strong Jewish community, which must have offered the prospect of a safe haven.

But for reasons that remain unknown, Touschek did not – or could not – take up his offer of a place in Britain. Instead, in September 1939, just as war was breaking out, he began studying physics back home at the University of Vienna, where he excelled in its famous school of theoretical physics. His professors there included Hans Thirring, best known for developing the “Lense–Thirring” frame-dragging effect of general relativity.

Touschek was aware of the dangers of staying in Vienna but, with the war now on, his options were limited. Despite his mixed Jewish/Catholic background, the Nazi authorities deemed Touschek to be a “first-class” [i.e. fully] non-Aryan and, at the end of his first year, he was suspended from the university. In January 1941 he was expelled entirely. Touschek’s chances of continuing to live and study in Vienna were disappearing fast.

To the heart of Germany

But Touschek then found protection and encouragement from the eminent German physicist Arnold Sommerfeld. Based at the University of Munich, Sommerfeld, then 72, was still an influential figure in the German physics community despite having been ostracized by the Nazi government for not complying with antisemitic policies. He had also refused to adhere to the notion of Deutsche Physik, such as denouncing relativity (which was deemed “un-German”).

Touschek had got in contact with Sommerfeld after writing to him to point out some errors he’d spotted in one of his books. The ensuing correspondence saw Touschek travel to Munich in November 1941 with Paul Urban, a physicist from Vienna who was giving a seminar there and who’d mentored Touschek following his suspension and then expulsion from the university. Won over by Touschek’s courage and determination, Sommerfeld crafted a plan for him to move to the University of Hamburg.

Profiles of genius and persecution

One of his former students would help Touschek continue his studies, with financial support from another ex-student, who now ran an electronics firm in the city. Moving to Germany might seem bizarre, but Hamburg was not as dangerous as Vienna, where his precarious status as a Mischlinge (mixed-race person) was well known. In any case, Austria was now effectively part of Germany and emigration – even to Italy – was not an option. Touschek simply hoped he could carry on with his physics, unnoticed.

Crucially for Touschek, there were scientists in Germany trying to protect their Jewish colleagues by hiring them for jobs in firms that were building equipment or devices for the Nazi military. Those scientists could claim that their Jewish friends’ activities were indispensable to the success of the war effort. Such a ruse would keep Jewish scientists away from the attention of the Gestapo and prevent them from being sent to concentration camps.

That at least was the hope. As it turns out, the Gestapo was fully aware of the employment of Jewish scientists. The Nazi authorities tolerated the practice, knowing that as soon as the projects were completed, those scientists would be arrested and dispensed with. Unaware at the time of those dangers, Touschek packed his bags and headed for Germany.

Berlin and the betatron

After visiting Sommerfeld in Munich and receiving his “blessings” for the journey, Touschek arrived in Hamburg on 1 March 1942. Immediately he contacted the company and scientific colleagues Sommerfeld had recommended, before looking for somewhere to live. Money was tight and his studies progressed, albeit slowly. Touschek was then distraught to learn that his grandmother had been taken to the Theresienstadt concentration camp where she died.

Depressed, and with Hamburg and other cities starting to be fire bombed by Allied forces, in November 1942 Touschek was on the move once again, this time to Berlin. Closer than ever to the dark heart of the Nazi regime, he got a job with Löwe Opta, an electronics firms with links to the military. At Löwe, Touschek came to hear of a project to build a 15 MeV betatron – a machine that could accelerate electrons to high energies.

It was being commissioned by the Reich Ministry of Aviation, which had sought the help of the Norwegian physicist Rolf Widerøe, who in 1928 had invented the principle by which such accelerators operate. The Nazis hoped the device would be powerful enough to create “death-rays” – beams of electromagnetic radiation that could strike down enemy aircraft in military operations.

Devices to produce death-rays had first been proposed in the 1920s by several scientists – supposedly including even Guglielmo Marconi and Nikola Tesla – and betatrons had later been suggested as a possible source. In 1941 the US physicist Donald Kerst built the first betatron as a research tool at the University of Illinois – and Widerøe wanted his betatron to be as good, if not better. In their hearts, though, every member of Widerøe’s betatron project knew it was unlikely that a betatron could ever really be put to military use.

Touschek formally joined Widerøe’s team at the end of 1943, where his knowledge of theoretical physics made him a vital member of the project. Aware that he was under surveillance by the Gestapo, Touschek wrote to his father to say he had signed his own “death contract”. In early 1944 he was summoned to the all-powerful Todt Organization, which senior Nazi engineer Fritz Todt had set up to build Germany’s concentrations camps and provide industry with forced labour.

Aware that he was under surveillance by the Gestapo, Touschek wrote to his father to say he had signed his own “death contract”

Luckily, his colleagues successfully appealed his call-up to the organization, insisting that Touschek was indispensable to the betatron. Despite further summons following – the last being in November 1944, when he was asked to appear with “blankets and warm underwear” – in each case Touschek managed to remain on the project. In one case his colleagues even appealed directly to General Erhard Milch, a close associate of armaments minister Albert Speer.

A march towards death

The betatron was completed at the end of 1944. But as 1945 dawned, it started to become obvious that Germany was going to lose the war. Orders came for the country to save important infrastructure and facilities from the advancing Allied armies. The betatron – a prized device – could still be of use and a plan was hatched to move it from the factory in Hamburg where it had been built to Wrist, a small village about 30 km north of the city.

Touschek and Widerøe completed the task on 15 March 1945. The following day, Touschek returned to Hamburg, arriving at his flat at midnight. At 7 a.m. the next morning, he was awoken by the Gestapo, who took Touschek away to the infamous Fuhlsbüttel prison, where he was kept for four weeks, initially in such miserable conditions that he thought of suicide.

The two faces of a wartime aerospace engineer: the controversial tale of Wernher von Braun

Colleagues from the betatron project came and briefly managed to improve Touschek’s situation, even bringing him some of his physics books. He was promised that a release would come soon. It did not. Instead on 15 April 1945, all 200 Fuhlsbüttel prisoners – Touschek among them – were ordered to march to the Kiel concentration camp, roughly 100 km north of Hamburg.

Unwell and weighed down by the physics books that he was carrying with him, Touschek fainted and collapsed on the road near Langenhorn on the outskirts of Hamburg. An SS officer accompanying the prisoners fired at Touschek, shooting him twice as he fell in a trench at the roadside. Blood pouring from his head, the officer and other prisoners continued their march, leaving Touschek for dead.

An SS officer accompanying the prisoners fired at Touschek, shooting him twice as he fell in a trench at the roadside

His wounds fortunately proved superficial. Touschek regained consciousness and was taken to hospital and then another prison, from which a betatron colleague had him released at the end of April 1945. Touschek would later tell his close friends this remarkable tale, which Amaldi also described in a letter from Widerøe who had visited him in prison. Lengthy descriptions appear as well in two letters Touschek wrote to his father in June and October 1945 (see Eur. Phys. J. H 36 1 for English translations).

Touschek never properly explained why he was arrested, offering different explanations to different people in the years that followed. In my view, he simply would not – or could not – account for his involvement with a classified project financed by the Minister of Aviation of the Reich. His work for the Nazi regime was not something that Touschek could ever easily come to terms with or forget.

Göttingen, Glasgow and Rome

After the war, the Allies permitted German science to restart under the guidance of Werner Heisenberg at the University of Göttingen, provided it was directed only for peaceful purposes. But with the Manhattan atomic-bomb project making particle accelerators a useful source of nuclear isotopes, Touschek’s experience with Widerøe’s betatron caught the eye of the British, who occupied the Hamburg region. Recognising his mix of theoretical and practical know-how, a plan was drawn up to bring him to the UK.

Aware that Touschek’s formal education was lacking, he was first allowed to obtain his diploma (master’s) in physics at Göttingen, where he did a thesis on the theory of the betatron. In 1947, after a further six months in Heisenberg’s research group, Touschek moved to the University of Glasgow, where he did a PhD supervised by John Gunn, with Rudolph Peierls as external advisor. He then spent a further three years there as a Nuffield lecturer.

Touschek’s five years in Glasgow were fruitful both scientifically and personally. He extended his knowledge of particle accelerators by following the construction of the Glasgow 350 MeV synchrotron and advising UK groups in Birmingham and elsewhere who were building their own devices. On the theoretical physics side, he came to know Max Born, who had found refuge at the University of Edinburgh after leaving Germany in 1933.

Touschek collaborated with him on the second edition of Born’s famous Atomic Physics book and discussed various physics problems with him, sometimes even explaining Heisenberg’s newest papers. In this period Touschek began to work on the so-called “infrared catastrophe”. Involving low-frequency photons emitted by accelerated charged particles, it was a phenomenon that was later to be relevant to all high-energy particle accelerators.

His credentials as a physicist now firmly established, in 1952 Touschek accepted a job offer from Amaldi as a researcher at the University of Rome. Returning to the city he had visited many times before the war – and where his aunt Ada had built a villa in the Frascati hills – Touschek found a vibrant intellectual atmosphere in the university’s physics institute. It played host to numerous distinguished international visitors including the Nobel laureates Patrick Blackett and Wolfgang Pauli.

With the war now firmly in the past, numerous national and international physics projects were starting up. One was CERN, the European particle-accelerator centre near Geneva, which Amaldi strongly supported and served as its first director-general. Rome was also home to two significant, new Italian projects – the Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN) and the Frascati lab – both of which were to play an important role in Touschek’s future.

Particle accelerators were fast becoming a fundamental research tool and were being used to discover a whole “zoo” of new particles. Touschek became interested in their symmetry properties and started studying neutrinos, proposing chiral symmetry transformations. At Rome, he worked closely with Wolfgang Pauli, who was trying to prove the charge–parity–time (CPT) theorem, according to which particle states don’t change if the particles become their anti-particles, if spatial co-ordinates are reflected or time is reversed.

Touschek’s understanding of CPT led him to realize that electron–positron colliders, which accelerate matter and antimatter along the same orbit but in opposite directions, would be vital for the future of physics. Convinced by the CPT theorem that electrons and positrons could be smashed into – and annihilate – each other, in 1960 he started leading a team of Frascati scientists to build a prototype. This was AdA, which began operations in February 1961.

To prove its feasibility as a research device, the 1.3 m-diameter device was transported to the Orsay lab near Paris where the first electron–positron collisions were observed by a team of French and Italian researchers in late 1963. Key to AdA’s success was the exceptional cadre of young theoretical physicists at Rome and the technical and scientific staff both in Frascati and Orsay. Although it never led to annihilation or produced novel particles, AdA was a testbed for a new breed of machines.

Lasting legacy

Touschek’s visionary thinking soon inspired other large physics labs in France, the Soviet Union and the US to build similar electron–positron colliders, opening the door to the discovery of new particles. AdA thus laid the foundations to the Standard Model of particle physics and changed the face of physics itself. Touschek was able to see some of these great events, such as multihadron production at ADONE and the discovery of charm quarks.

In 1977 he spent a year’s sabbatical at CERN, where the Super Proton–Antiproton Collider and the Large Electron–Positron collider (LEP) were going to be built. Not a fan of big international enterprises, which Touschek felt were becoming too bureaucratic and complex, he nevertheless enjoyed keen discussions with Carlo Rubbia about stochastic cooling – a technique to create a stock of antiprotons that could be annihilated with protons to discover the carriers of the weak force.

However, in February 1978 Touschek’s health started rapidly declining. After a number of hospitalizations, he asked CERN’s then director-general, Léon Van Hove, for a car to drive him to Innsbruck in Austria. The country of his birth, it was a place he had loved all his life. Touschek, who died on 25 May 1978, never got to witness the renaissance of particle physics – the experimental discovery of the W and Z bosons, the top quark and the Higgs boson – in the years and decades that followed.

But his legacy as a visionary scientist, who showed wisdom, stamina and perseverance – despite all the odds – lives on.