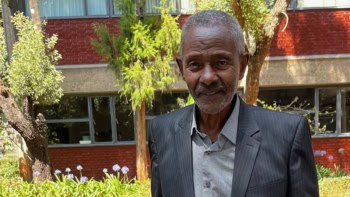

Materials scientist Arnab Basu, head of radiation-detection technology developer Kromek, talks to Tushna Commissariat about founding a spin-off, the challenges of COVID-19 and looking to the future

What fostered your initial interest in physics?

I grew up in Calcutta, India, and did my schooling there. My dad was a materials engineer – a “metallurgist”, in those days – who graduated from the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, and worked for a British company before ultimately starting his own business back in India. So I grew up in an environment of bold entrepreneurship as my dad built the family business – a materials-processing firm. Science and technology were very much part of my growing up.

I had a keen interest in what went on in the factories from a very young age. Not that I was deeply interested in physics when I was in school – I was more interested in music and acting at that age. But I ended up doing a natural sciences degree at Calcutta University, studying physics, chemistry and mathematics. Then when I was 21, I went into the family business. But within two or three years, I realized that wasn’t the place I wanted to spend my entire life. It didn’t feel right. The only way to get out of such a situation, particularly in India, was to become a student again – it was the most conflict-free way of saying I wanted to do something different. I ended up in the UK, doing materials engineering in Northumbria University. It was a very quick decision.

What was your experience like there, and what did that lead on to?

Northumbria was fantastic. I got a first-class degree and had an amazing time as well. As a mature student – by that time, I think I’d grown up a little bit – I was more interested in what was going on in the classrooms rather than in student politics. But also, I felt I had to prove something. It was the first time I came out of my comfort zone, in a way.

After that, I worked for a local company in North Tyneside, Elmwood Sensors, that was part of an international engineering group. That role was very much materials-science-based. In those days Elmwood Sensors had R&D activity at Durham University, so I got to know the university quite well. Durham kindly offered me a fully paid scholarship PhD, and I jumped on it.

My PhD was in materials science, based in a physics department. So I always say I did “the dirty end of physics”, really, in condensed matter. It was, again, a very enjoyable experience. It’s a great city to be in and once you’re in Durham, you never leave Durham. I took the PhD as a job. I finished within three years, and I got a prize for the best thesis for condensed-matter physics at Durham as well, which was nice to have.

How did you get from there to helping to found Kromek?

When I was doing my PhD, I fancied going to work in the City. The world of finance fascinated me. So, as I was finishing, I started to apply for jobs and I had one lined up in investment banking in London. But when I finished, I went travelling for four months with my wife. And while we were travelling, Durham was trying to spin this business out. The founder, Max Robinson, decided to invest some money in this spinout and they were looking for somebody to lead it.

I was contacted by Durham because they knew I had an interest in entrepreneurship and I loved science and technology. So I decided to give it a go. In May 2003 I returned to the UK, and that month the company operationally started. We had one patent that the university wanted to commercialize, and were based in the technology-transfer offices at Durham. So I had a room, a secondhand computer and a piece of paper. That’s how Kromek started.

What were the early years of Kromek like, and how did you get to where you are now?

Kromek came out of a roughly 20-year research history at Durham University. In the mid-1990s, as a leader of a European funding consortium, Durham developed an IP to grow cadmium telluride. That’s when the technology part began, and then in 2003 that was commercialized.

In the early days of Kromek, the business model was simple. We’d make a lot of these materials and scale it up. But we changed tack once we started to get an understanding of the market; we began to raise money and we realized it would be better to add more value to our offering. So we started developing electronics and application expertise. In 2013 we acquired one of the largest cadmium zinc telluride manufacturers in the US – so we are now a UK and US business, with 50% of our workforce in the US.

Max Robinson also had expertise in security imaging, which is how we got involved in that. Our first product happened to be a barcode scanner to detect liquid explosives – a product that is still used today in many airports. We also started seriously engaging with the US Department of Defense in 2008, which led to us protecting New York City and other cities against dirty bombs through large networked solutions for security.

We started making a spectrometer in 2009 – it was the GR1, which still remains the world’s smallest room temperature spectrometer, at the size of a matchbox. In 2011 we had just begun importing and distributing in Japan when the Fukushima disaster happened. The GR1 was used in the disaster aftermath because it was so small and very high resolution, ideal for getting in the right spots to categorize reusing shielding, for example.

So there are some very exciting technologies that have been developed in Kromek. We do medical radiation detection but we also do security – protecting ports, borders and cities – working with a fantastic customer base around the world.

What kind of skills are you looking for when hiring employees at Kromek?

The breadth of Kromek’s technology is big – we offer the whole platform. So we are interested in electronics engineers, semiconductor scientists, semiconductor engineers, process engineers, photonics scientists, core physicists and more. We do systems modelling and algorithm developments for software development. We are increasingly getting into artificial intelligence on a number of fronts – around bomb detection and in other parts of our portfolio. We’ve got a team of data scientists and AI specialists who are delivering product AI solutions.

Of course, we also need all the other important functions – sales, marketing, digital marketing, account management, product management and all the associated services that go with running a company. Core skills are important, but I’m always looking for personalities and what people bring to the business, as well. Will they fit into the team? Are they able to contribute and interact with other people? Emotional quotient is important.

Recognizing the value and values of material science

What advice would you give to young, early-career scientists considering launching a spinout company from their university?

Entrepreneurship is an interesting journey. It is like learning to fly while you’re flying, so the challenges can be very big. Taking a realistic view of your financing is extremely important. Starting out with a vision of what it is you’re trying to build is key. And you have to believe in it completely.

Particularly with technology businesses, you have to bring a lot of people along with you, fixed on that vision, and go through the ups and downs that come with it together – it’s not going to be a straight line. When you start out, you have nothing except an idea. You’ve got to make that idea work, and then you have to prove that people are willing to pay to buy it.

Don’t try to be an expert in everything yourself because you’re not

Surround yourself with the best people you can afford. My philosophy is very simple: everybody in the business is better skilled than me, and they’re better at doing their job than I am. Your job as chief executive is about creating the vision, leading, co-ordinating and making sure all those experts and experienced people you’ve got with you are driven towards a common goal. Don’t try to be an expert in everything yourself because you’re not.

Science is about breaking new frontiers, inventing new things and increasing the knowledge that exists each day. When you come to the other side of industry and entrepreneurship, you are generally trying to convert that science into usable products or services. It’s about solving somebody’s problem using the science – and that means that you have to be completely customer-focused.

Having a piece of technology and having a successful business are two very different things, because technology is only one element of a successful business. Making sure you’ve got a good team involves not just brilliant scientists and brilliant people, but a group of people who gel with each other, work well together and have a common goal. Also, without taking risks, you’re not going to succeed. In innovation, there’s a clear understanding that if you haven’t failed, then you haven’t tried. You learn more from failures than when you succeed. It’s an exciting journey that nothing else can replace.

What is a day in the life of Arnab Basu like?

It varies from day to day. I have my internal responsibilities as the chief executive, working with my team. I’m a people person, so – in our previous norm – I’d be going from desk to desk talking to people, to understand what’s going on and trying to solve problems or enable and encourage my employees. I used to travel a lot, so I spent a lot of time with customers and working on related issues. That’s what really gives me a buzz: sitting in front of a customer and learning what they’re trying to achieve and how we can help them. I also spend time on strategy, in terms of looking forward and seeing what technology and what products we have, what markets they fit in and how we can expand them. It’s really wide-ranging stuff. It is all market-driven and market-focused, really.

How has the global pandemic altered the operation of your business?

COVID-19 has presented some unprecedented challenges. We’re still a relatively small business, operating on four sites, but with a global customer base. Some areas were badly affected. For example, in our medical-imaging segment, no hospital was focusing on installing new scanners while they were trying to understand how to handle the crisis.

We were lucky in a way, because we had taken steps towards adapting to new ways of working throughout the previous year. We did a pilot of homeworking 10 days before the first lockdown came into effect – but that was not because we had a grand vision of what was going to happen, it was just luck. We have learned a lot in the last year, and we’ve adapted. We’re a manufacturing business so we still have to have people in to do things in labs, to make stuff and build prototypes. You just can’t do that remotely, so we had to adapt our working conditions.

Of course, commercially, the business did suffer in the first half of 2020. But Kromek’s technology products are still needed in the market for very simple reasons. COVID hasn’t got rid of cancer, so early detection of cancer will still make a difference in people’s lives. The need to protect against terrorism hasn’t gone away, so products in that arena are still in demand. This growth market remains strong for us and will continue to be so.

What we are doing in biodetection is especially pertinent – developing a broad-spectrum monitoring system for airborne pathogens, on a very wide area basis. This is something that doesn’t exist today. These systems could sit in places where people are coming in and going out of countries, sampling air all the time. Any new variants, any new mutants, any novel viruses could be picked up and reported at an early stage.

Innovation will be key for us as a country, as a world and as a company. We must make sure we keep innovating, solving problems and providing solutions. That helps commercially in business – but it also aids humanity. That’s what the ultimate aim of science is and always should be.

What is your advice for students today – in a time when the future may seem bleak?

The world might be bleak today, but opportunities are borne out of situations like this. Fundamentally, the need for science, innovation and for good people to drive the world forward will not change. Any physics graduate already has the advantage of being able to look at a career from a very wide spectrum, whether you want to go into finance, product development, AI, data science or many other things.

I would say try to discover what you really want to do because it’s important that you pursue a career that you’re passionate about. I think the current generation of students are much more socially aware and put a lot more importance on the value of what they’re doing than my own generation. Our first priority was getting a mortgage and buying a car – we were much more materialistic, I think. That brings a different perspective and also a different way of looking at your career.

I think being a student now is not such a bad thing. COVID-19 will be behind you when you actually enter the job market. And there are some valuable skills that this pandemic has pushed people to learn. So use those, focus on those. Ultimately, skills are always needed.