The European Space Agency (ESA) is to launch a probe to visit a comet originating from the outer solar system. The €150m Comet Interceptor spacecraft, proposed by a team led by UK-based researchers, will launch in 2028. It will be the space agency’s first so-called “fast” or F-class mission, which take under a decade from selection to launch and weigh less than 1000 kg.

The mission will take off together with ESA’s Ariel satellite, which will scrutinise the atmospheres of extrasolar planets. Once in space, the Comet Interceptor will travel to the L2 Lagrange point– a gravitational-balance point over a million kilometres beyond the Moon’s orbit – where it will lie in waiting for its quarry: a comet on its first dive in from the very farthest reaches of our planetary neighbourhood.

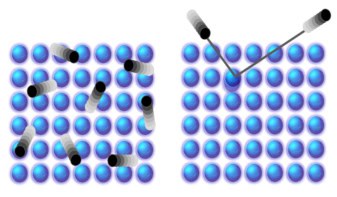

Unusually for a space mission, however, Comet Interceptor does not yet have a target in its sights. But by being placed at the L2 point it can wait, for several years if need be, until the right comet is spotted on an inward trajectory. Once an object has been selected, the Comet Interceptor will observe the comet using a collection of cameras and a mass spectrometer mounted on three separate spacecraft, enabling astronomers to build a detailed picture of its composition and shape.

The first mission to a body from another solar system would immediately give us accurate data on these objects

Alan Fitzsimmons

“We’ve learnt a huge amount about [comets], however, all of these past targets have been affected by their numerous passages past the Sun,” says Geraint Jones from University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory, who is Comet Interceptor’s lead proposer. Indeed, each swoop into the inner solar system warms a comet’s frozen surface, alters its shape and causes ice-obscuring dust to accumulate on its nucleus. “A comet nearing the Sun for the first time since its formation should be pristine and unprocessed, providing a much greater insight into the nature of these ancient bodies and their role in the formation of Earth and the other planets,” adds Jones.

Astronomers will search for an object that could be studied by Comet Interceptor using sky surveys like Pan-STARRS, ATLAS and the forthcoming Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST). “With LSST observing more than three magnitudes deeper than current surveys, we will routinely pick up new comets at a greater distance than ever before, well outside the orbit of Saturn,” says mission team member Michele Bannister from Queen’s University Belfast. “So for the mission target, we’ll have years to study it with telescopes on Earth before Comet Interceptor flies across to it. It’s possible the mission target could be discovered even before Comet Interceptor launches.”

From another system

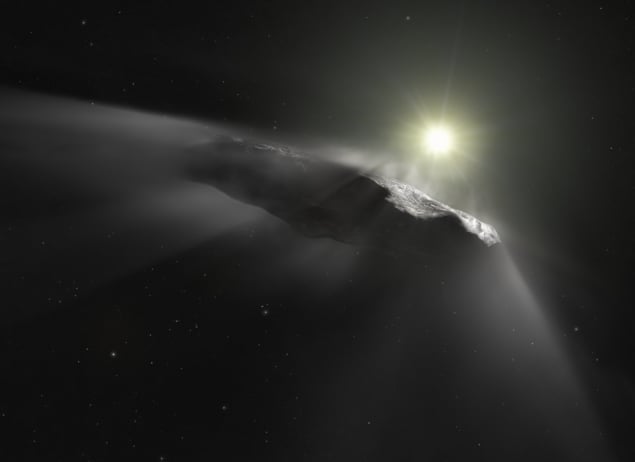

One exciting possibility is that the mission will be able to intercept a comet or asteroid that originates from beyond our solar system. The first interstellar object of this kind, dubbed ‘Oumuamua, was observed wandering through our neighbourhood in 2017. But its discovery occurred much too late to arrange a spacecraft fly-by and it duly left the inner solar system, leaving many unanswered questions. ‘Oumuamua: visitor from another star

“The first mission to a body from another solar system would immediately give us accurate data on these objects,” says Alan Fitzsimmons, an astronomer from Queen’s University Belfast who is not part of the Comet Interceptor team. “Comparing this with our detailed knowledge of asteroids and comets in our own Solar System will clarify what these objects are truly like and how they might be altered by their voyages between the stars.”