By Margaret Harris at the AAAS meeting in San Jose

A giant cloud of hydrogen gas is barrelling towards the Milky Way faster than the speed of sound, and dark matter may hold it together long enough to produce a spectacular outburst of new stars in the night sky – but not for another 30 million years.

The cloud – which is known as Smith’s Cloud after Gail Bieger-Smith, who discovered it as an astronomy student in 1963 – is one of several starless blobs of hydrogen known to exist in the space between galaxies. According to Felix “Jay” Lockman, principal scientist at the US National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Green Bank Telescope, such gas clouds are, in effect, “construction debris” left over from an earlier age of galaxy formation. “These are parts for remodelling your house that didn’t arrive by the time the contractor left,” Lockman told an audience at the 2015 AAAS meeting in San Jose, California.

What makes Smith’s Cloud special, he added, is that we know so much about it. We know its size (4 kiloparsecs long), its distance from our solar system (about 12 kiloparsecs) and its total space velocity (300 km s–1). And since 2008 we’ve also known that it is heading straight for us – or, rather, for a spot in the Milky Way about 10 kiloparsecs out from the centre.

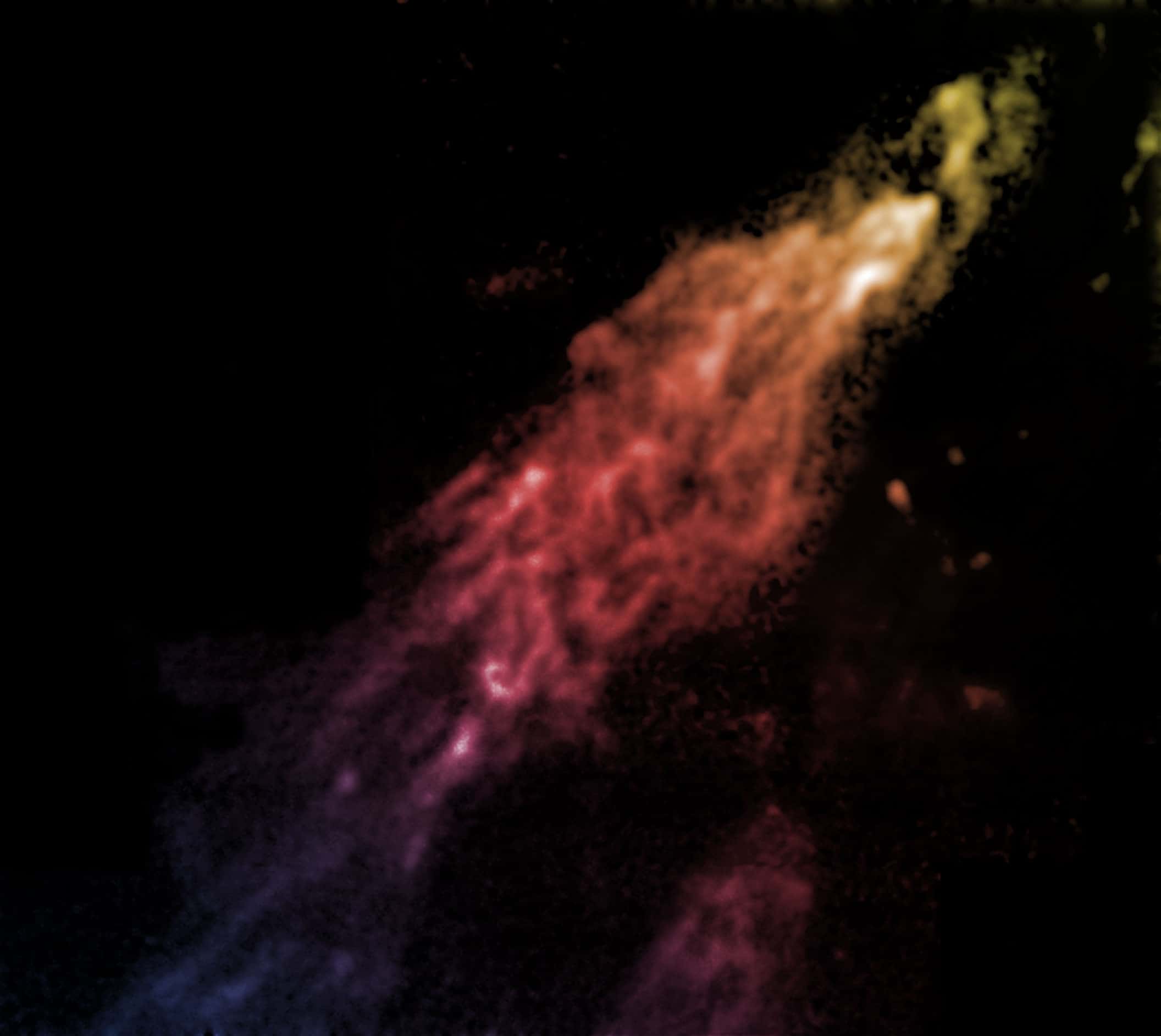

What wasn’t known until recently, Lockman explained, was why the cloud hadn’t fallen apart. As it approaches the galactic disk of the Milky Way, tidal forces ought to be tearing it to shreds – yet as the image above shows, it is still very much there. In 2013 observations made at the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia and the Very Large Array in New Mexico indicated that magnetic fields within Smith’s Cloud might be helping to maintain its integrity, and Lockman said that more detailed observations are expected later in 2015.

However, theoretical modelling carried out last year offers an even more intriguing possibility. In essence, the researchers (led by Matthew Nichols of the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland) showed that a simulated high-velocity cloud composed solely of hydrogen would not be able to survive its passage towards the galactic disk – but a hydrogen cloud surrounded by a dark-matter envelope would. Hence, the starless blob of hydrogen we know as Smith’s Cloud could be merely the visible-matter component of a much more massive dark-matter “halo”, Lockman said.

Another mystery about Smith’s Cloud is where it comes from. Hydrogen is, of course, ubiquitous throughout the universe, and Smith’s Cloud contains around 2 million solar masses of it. But recent measurements by the Hubble Space Telescope found traces of other elements as well, including silicon and oxygen. Further analysis of these data may tell us more about the cloud’s origins, Lockman told Physics World.

Regardless of where it comes from or what keeps it together, Lockman expects that Smith’s Cloud will eventually contribute enough hydrogen gas to the Milky Way for several million new stars to form. And while galactic dust might prevent our distant descendants from seeing those new stars emerge in the night sky, an Earth-bound telescope operating at infrared or radio wavelengths would certainly detect them. “We’d be able to pick ’em up,” Lockman said confidently.