Large quantities of scientific data are being lost because governments and scientific funding agencies are not investing enough in large databases according to US researchers writing in Nature this week. Richard Firestone from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and colleagues say that databases have traditionally been maintained by committed individuals or small groups. However, large amounts of data have been lost because there is no commitment to maintaining certain databases. Meanwhile another US scientist, Sergey Brin from Stanford University, has claimed that "within five years [the] Web search engine, as we know it, will no longer exist" (Nature 405 117 and 112).

Examples of lost data include the results of heavy-ion experiments at the Bevelac accelerator at Berkeley. The accelerator stopped running in 1993 but much of the data – which are relevant to research into solar neutrinos, nucleosynthesis and cosmic rays – was never published in any form. “Scientists will have to wait decades before these data are remeasured,” say Firestone and colleagues. They also criticize plans for the long-term storage and dissemination of data from the $600m relativistic heavy-ion collider (RHIC) at the Brookhaven National Laboratory and the CEBAF accelerator at the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility. However, plans to build ‘virtual’ observatories (see Astronomers look to ‘virtual’ observatories) to analyze data from telescopes and satellites are praised by Firestone and colleagues.

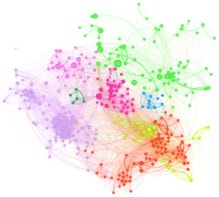

But storing the data is not enough, writes Declan Butler in a related article, you must also be able to search or index it. Only 50% of the billion pages on the Web today have been catalogued, and it is expected that over 100 billion pages will be added over the next two years. The only solution is to develop a new generation of search engines for scientists, according to Butler. New tools, such as XML (eXtensible Markup Language) – the successor to HTML – should make it possible to restrict search terms to scientific papers, while the rise of specialised science portals will also help, he writes. And new search algorithms – which take account of how many times different pages have been accessed – should help direct users to the most relevant material. The first two prototypes for such advanced search engines – Google and ResearchIndex – can already be accessed on the Web.