US agencies have warned against the uncontrolled use of the new 5G spectrum band, which they say could significantly affect weather forecasting. Wireless companies that won an auction – held by the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) in March – will now begin using the 24 GHz band for 5G technology, which will operate about 100 times faster than current networks. Yet the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), part of the Department of Commerce, and NASA say that its use could interfere with the detection of water vapour in the atmosphere.

It would be like noisy neighbours moving in next door with a very loud transmitter

Jordan Gerth

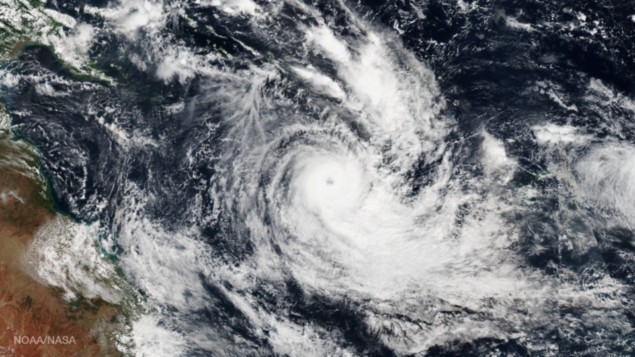

The disagreement between US government departments and the mobile-phone industry over 5G use has been largely private for several months but the issue was made public in Congressional testimony on 22 May. Acting NOAA head Neil Jacobs asserted in a hearing that potential interference from 5G networks could reduce the accuracy of weather forecasts by up to 30%. That loss would leave forecasts no better than they were in 1980, Jacobs added, and it would give coastal residents two to three days fewer to prepare for impending hurricanes.

Jordan Gerth, a meteorologist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says that the water-vapour signal lies in the spectrum band between 23.6 and 24 GHz and that 5G transmissions could easily leak into that range. “It would be like noisy neighbours moving in next door with a very loud transmitter,” he told Physics World.

A question of sensors

Yet the Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association (CITA) – a trade association that represents the US wireless industry — disagrees. “The dire predictions right now…about the impact of 5G on current weather forecasting are wrong on the merits, on the facts, and on the process,” Brad Gillen, CITA executive vice president, wrote in a blog. “Now, in a last-ditch effort to undo five years of work and multiple administration and FCC decisions, the commerce department is misleading Congress and the press.” In the blog, Gillen says that the move to stop the use of 5G is based on protecting a weather sensor – the conical microwave imager/sounder (CMIS) — that does not exist as it never went into operation having been cancelled in 2006.

Gerth, however, says that the CMIS’s successor — the Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder (ATMS) – is in operation aboard the Suomi NPP polar-orbiting satellite and is currently working at 23.8 GHz, which is within the range of the 5G wireless transmissions once they start at 24 GHz. Yet the CTIA’s chief communications officer Nick Ludlum asserts that the ATMS is “smaller and has a wider beam width” than the cancelled CMIS sensor, which “makes it less sensitive to the nearly 5G signals”.

Many want the issue to be resolved before the World Radiocommunication Conference, which will begin on 28 October in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. That meeting is set to debate the future and growth of 5G radio technology and it is hoped that the US agencies will have settled the argument by then and will have put forward a unified proposal. One potential compromise, which Congress is exploring, would permit 5G telecommunications at 24 GHz but set a limit on their volume.

Meanwhile, forecasters express concern that the growth of 5G could threaten other spectrum bands. Gerth says that fresh debates may emerge around the use of 36-37 GHz, which is utilized to spot rain and snow or 50 GHz that detects atmospheric temperature. “It’s not as if 5G has to go into 24 GHz or nobody gets it,” he adds. “There’s plenty of spectrum away from the weather bands.”