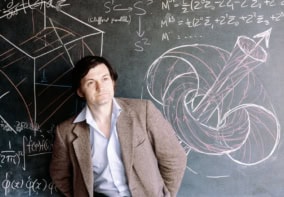

The theoretical particle physicist Murray Gell-Mann, who was awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize for Physics, has died aged 89. In the 1960s Gell-Mann developed a method to categorize the huge number of particles that were being created at particle accelerators worldwide. Gell-Mann’s model also predicted the existence of another fundamental type of particle that makes up particles including protons and neutrons. Gell-Mann dubbed them “quarks” and they were later discovered experimentally at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) in the US.

Born on 15 September 1929 in New York City, Gell-Mann obtained a BSc in physics at Yale University in 1948. Three years later, he was awarded a PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology before he joined the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University in 1952. After a stint at the University of Chicago, he joined the California Institute of Technology in 1955, where he remained for the rest of his career.

From the 1950s through to the 1970s, Gell-Mann played a leading role in particle physics. In 1961 Gell-Mann – together with the Israeli physicist Yuval Ne’eman – independently came up a with scheme that brought order out of the chaos of the “particle zoo” that was created by the discovery of some 100 kinds of particles in collisions involving atomic nuclei.

Dubbed the “eightfold way”, it involved ordering these subatomic particles onto clusters of eight and 10 based on a mathematical symmetry known as “SU(3)”. While the model was successful at describing existing particles and their interactions, it also opened the door for predicting the existence of new particle states, which were subsequently discovered. It was for this work that he won the 1969 Nobel Prize for Physics.

Using the eightfold way, in 1964 Gell-Mann and George Zweig independently proposed the existence of a new type of particle that made up particles such as neutrons and protons. Gell-Mann’s decision to call them quarks came from his interest in language, which was evident at an early age. Indeed, he was only 10 years old when he first leafed through a copy of Finnegans Wake – the novel by James Joyce that later provided him with the word quark in the phrase “Three quarks for Muster Mark”.

Back in the early 1960s, Gell-Mann wanted his new name for the components of protons and neutrons to sound like “kwork”, but he did not know how to spell it. However, since quark – which also describes the cry of a gull – was clearly intended to rhyme with Mark, Gell-Mann had to find an excuse to pronounce it “kwork”. But as Finnegans Wake is about the dreams of a publican and many phrases in the book are derived from calls for drinks at the bar, Gell-Mann argued that “Three quarks for Muster Mark” might actually mean “Three quarts for Mister Mark”. In 2002 he was able to study Joyce’s original manuscript for the novel during a visit to Dublin.

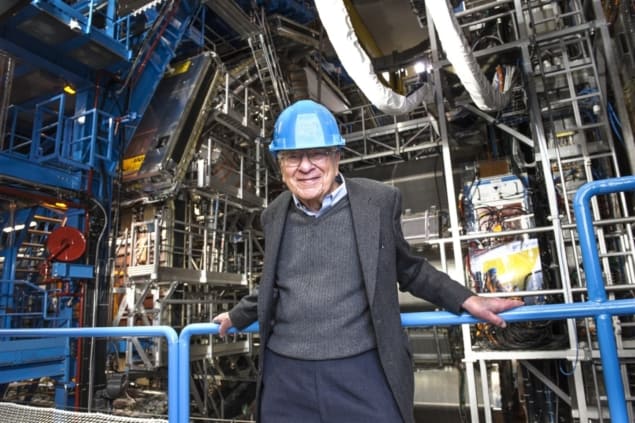

The existence of the quark was confirmed by deep inelastic scattering experiments at SLAC in 1968 and experiments have since provided evidence for all six flavours of quark — up, down, strange, charm, bottom and top. Quarks are permanently confined by forces coming from the exchange of gluons in the nucleus and Gell-Mann and others later constructed the quantum-field theory of quarks and gluons, known as quantum chromodynamics.

A love of language

In later life Gell-Mann was able to spend more time in other fields, indulging his interest in language. In 1984 Gell-Mann co-founded the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico – an independent multidisciplinary centre that brings together researchers from different fields. In the 2000s Gell-Mann received funding to organize an international group of linguists, archaeologists, physical anthropologists and geneticists to explore distant relationships among human languages. This led to the establishment of a research project at the Santa Fe Institute that focuses on the origins, evolution, and diversity of human languages.

A self-described perfectionist when it came to language, Gell-Mann, was not satisfied with the written version of his Nobel lecture and did not submit it for publication. “I tried to write a better one, including an adequate discussion of quarks, and agonized over it for months,” he told Physics World in an interview in 2003. “But in the end, I did not finish it in time for it to be included in the volume.” Indeed, the publication of that Physics World interview was itself delayed by many months as Gell-Mann agonized over the proofs.

In the same interview, Gell-Mann admitted that he often had trouble with writing projects. “On many occasions it has delayed my writing up research, often by a year or more. By that time, it has sometimes happened that another theorist has had a similar idea and has written it up more quickly.” Indeed, in 1994, Gell-Mann published The Quark and the Jaguar – his only popular science book – in which he wrote about his ideas on simplicity and complexity. It too was apparently hit by delays, and failed to sell well. The many worlds of Murray Gell-Mann

Gell-Mann was also highly critical of how others wrote about him including his Caltech colleague Richard Feynman – who failed to mention Gell-Mann’s contributions to the development of the theory of the weak nuclear force in the first edition of his best-selling book “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!”. Gell-Mann was also upset at how he was portrayed by the science writer George Johnson in his widely-acclaimed biography of Gell-Mann entitled Strange Beauty. “He got many things wrong about physics, about my family and my personal life, and about my motivations in writing papers the way I did. I could so easily have set him straight,” said Gell-Mann.

“As with most any book of such length and complexity, there were some errors — most very minor and all corrected in later printings and in an errata sheet on my website,” Johnson told Physics World. “You can be sure that Murray made me suffer over every one.”

Gell-Mann won many other prizes during his career including sharing the Ettore Majorana “science for peace” Prize in 1989 and the Albert Einstein Medal in 2005 that is awarded by the Albert Einstein Society in Bern. He also served on the US President’s science advisory committee between 1969 and 1972 and on the US President’s committee of advisors on science and technology from 1994 to 2001.