John Budden calls for certain areas on the Moon to be protected from human interference so that they can be dedicated to radio astronomy

When the team behind the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) released the first images of a black hole in April, the observation made headlines around the world. The spectacular picture of the black hole at the heart of the Messier 87 galaxy was made possible thanks to a worldwide network of radio telescopes, which painstakingly combined their signals to give the necessary resolution to take that first image.

Since its conception in the 1930s, radio astronomy has gone from strength to strength. Just witness the success of the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR), which is mainly based in the Netherlands, or the excitement around the planned Square Kilometre Array – a huge radio telescope that is being constructed in southern Africa and Australia. Both these observatories are expected to reveal vast new areas of the universe that have never been seen before.

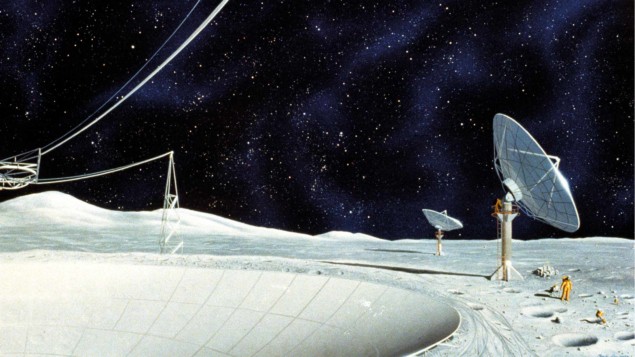

The Moon offers a unique vantage point that is free from atmospheric effects and human-caused interference

While all these facilities are Earth-based, the Moon, however, offers a unique vantage point that is both free from atmospheric effects and human-caused interference. Some areas on the Moon are ideal because radiofrequency and thermal noise – both of which are radio astronomers’ greatest enemies – could be lower there than even on Pluto. Indeed, China is already planning to create a prototype Earth–Moon–space very-long-baseline experiment that will study solar bursts, space-weather events and the near-Moon low-frequency radio environment (see “Exploring the far side”).

It seems only a matter of time before humans once again step foot on our nearest neighbour, with many space agencies and even private firms planning manned missions within decades. And that’s before we get to actual space colonization and the need to mine water for the conversion into rocket fuel – hydrazine – or for drinking. However, all these endeavours may be a threat to conducting radio astronomy on the Moon. That’s why I believe that we must protect certain areas for radio astronomy – much in the same way as we reserve electromagnetic quiet areas on Earth for terrestrial radio astronomy.

Treaty changes

The most attractive places on the Moon for radio astronomy are the so-called permanently shaded regions (PSRs). These include the Shackleton crater, which is located close to the lunar south pole. Research shows that there is little evidence of exposed ice in this crater, which makes it less attractive for manned mining objectives. A further bonus of the Shackleton crater is that it is bounded by a crater rim that is sunlit for 92% of the year thus providing a platform for a solar-power station to feed systems within it.

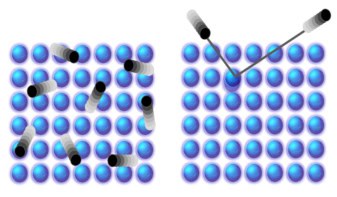

All in all, the Shackleton crater is ideal for a lunar equivalent of LOFAR, which could operate within 1–10 MHz and be deployed by unmanned rovers. This so-called Shackleton low-frequency antenna array would have little value to astronomy in isolation because of its low resolution of between 0.1° of arc at 10 MHz and 1° at 1 MHz. But we could also build a network of precision-timed very-long-baseline interferometry – much like that used for the EHT. This long-baseline array would be able to search for sources of cosmic magnetism ranging from nearby galaxies to pulsars. It would also be used to conduct whole-sky surveys.

This network would consist of telescope arrays located at four other PSR basins in the southern polar region – namely Amundsen, Hedervai, Idel’son, Wiechert. The Bosch basin, which is nearer the lunar north pole could also be used, if required. Like Shackleton, all these areas show little evidence of having deposits of water ice so would hopefully be of little interest to mining syndicates.

Choosing locations, however, will be the easy part – we need to do much more. The Moon treaty section of international space law allows the Moon to be mined –specifically for the extraction of natural resources. But this same treaty also prohibits any rights over territories on the Moon. I believe the treaty must now be revised to exclude these six lunar areas from mining activity and to reserve them solely for radio astronomy. If mining starts in the proposed areas, the resulting machinery and infrastructure will swamp these PSRs with thermal heat and radiofrequency noise – rendering them useless to the astronomy community.

The process of amending the Moon treaty is likely to be far harder than funding the lunar vehicles and rockets to set up these radio arrays. After all, just look at what is happening to the environment here on Earth. Despite the best efforts of environmentalists, many critical areas on our planet are quickly disappearing, mostly from the pressure to exploit natural resources. The lunar polar regions are even more remote and out of sight, so protecting them is going to be even harder.

Time is running out. Scientists need to start voicing their concerns to make sure we can exploit these areas and build on the recent success of radio astronomy. The work is vital as extending such endeavours to the Moon will greatly expand our understanding of the universe.