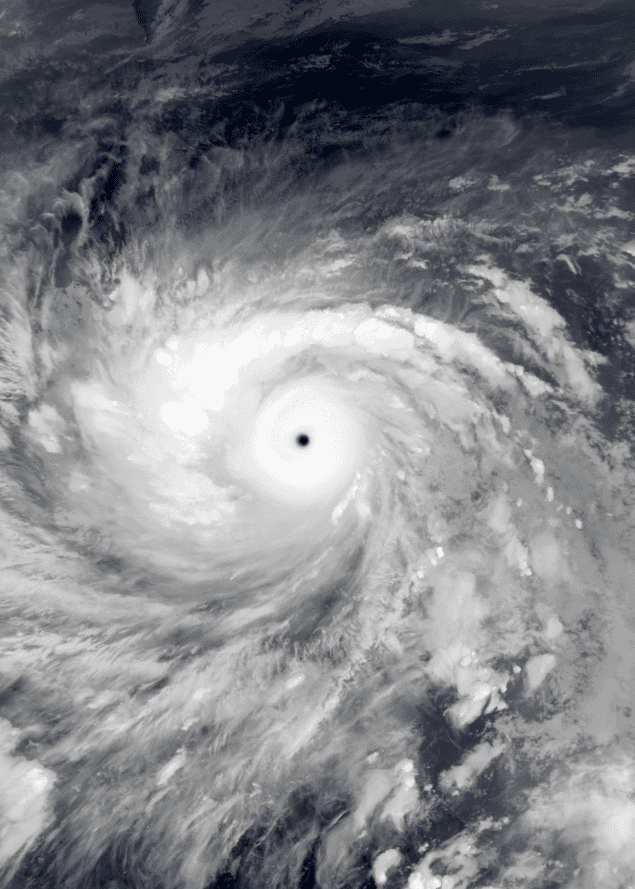

In November 2013 super typhoon Yolanda devastated much of Southeast Asia and killed over 6300 people. Known internationally as Haiyan, the tropical cyclone was one of the most powerful ever recorded.

Diego Boleche, a fisher and seaweed farmer from the village of Cagaut in the Philippines, and his family were lucky to survive; Yolanda destroyed their fishing boat and nets. Eventually Boleche managed to make himself another boat. However, the combination of typhoon-damaged reefs and competition from fellow fishers meant that he struggled to catch enough fish to feed his family, let alone pay the bills.

The fishing industry was particularly hard-hit by the super typhoon and Boleche’s story is a familiar one. After Yolanda many fishing families had to borrow money or rely on grants to rebuild their livelihoods. In many cases fishers found themselves in a precarious situation: lacking savings to tide them through the disaster, not having sufficient credit-rating to take out a bank loan and without access to any kind of income support. Instead they were forced to rely on informal loans from their patrons, handouts from aid agencies, and borrowing from loan-sharks.

This somewhat haphazard way of re-financing the fishing industry after Yolanda has had knock-on effects. Although patron-client relationships may help people recover from the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster, a new study indicates that they may also erode long-term sustainability, particularly if climate change makes disasters like Yolanda more frequent.

Liz Drury O’Neill from Stockholm Resilience Centre in Sweden and colleagues gathered data from Philippine fisherfolk, fish traders, NGO representatives and municipal- and provincial-level government officials in September 2015, approximately two years after the super typhoon, and October 2017. They asked about the impact of Yolanda on people and their livelihoods, what measures they had to take to respond to the disaster, and what changes they had seen over time.

The research uncovered an inequity in disaster relief for coastal fishing communities. Many fishers reported how those with political connections to local government received donated boats more quickly. Due to previous overfishing problems, donors were urged to give only small boats to avoid the fishing pressure of larger boats on dwindling stocks. But this well-meaning directive appears to have backfired, resulting in a far greater number of boats in total.

“There are a lot more boats after Yolanda,” explained one fisher. “Before, every Thursday market day there was lots of space to land at the port, now you have to tie up ten boats back and then climb across them all.”

In addition, this homogenization of the fishing fleet has constrained the choice of fishing grounds because small vessels are less able to cross open channels or move away from local reefs.

Fish traders, meanwhile, found themselves pressurised into acting quickly to secure their supply of fish. “If they didn’t get cash for the clients quick enough then the fishers transferred to other patrons,” says Drury O’Neill. “The traders turned to informal finance options if they didn’t have the cash flow themselves, which were mainly their own patrons in the bigger cities like Manila or Iloilo and then the loan sharks around Concepcion and Estancia.”

Writing in Environmental Research Letters (ERL), Drury O’Neill and her colleagues conclude that whilst the donations, patronage and aid helped to mitigate short-term vulnerabilities, they also compounded previous problems, including already declining fisheries, weak governance and lack of financing options, and potentially undermined the long-term sustainability of the fishery resource. With climate change likely to bring more extreme weather events, this kind of scenario could become more common. The authors suggest that the patron-client relationship must be taken into account when implementing disaster relief packages.

“Governments and NGOs can minimise the dependence on patronage and economic vulnerability of fishers by better engaging with managers and representatives closer to the ground,” says Drury O’Neill. She also points out how natural disasters can deepen the indebtedness loop associated with patronage, and that perhaps this can be broken by supporting finance schemes that offer people new options.

In Diego Boleche’s case that is exactly what happened. He was given technical training and a cash grant from international NGO WorldFish, enabling him to diversify and start a sustainable milkfish farm. Today he and his family are better off than before and the fish farm gives them security and independence.

- Diego Boleche was not directly involved in Drury O’Neill’s research but his story illustrates the issues explored.