Approximately 10 metals occur in the human body naturally as chemical compounds that are stored and used by tissues. Copper and iron oxides, in particular, are required for cellular activities throughout the body.

When the body mishandles or incorrectly processes these copper and iron oxides, however, tissue damage – especially in the brain – can occur. Researchers have suspected that pathological structures in the brain called amyloid plaques, which have been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, might be where some of this damage happens.

An unexpected discovery detailed in Science Advances may support this damage-centred hypothesis.

Researchers have found elemental copper and iron deposits alongside copper and iron oxides in the brains of two individuals who died with Alzheimer’s disease.

“We were not expecting to see the elemental forms [of copper and iron],” says Neil Telling, a professor of biomedical nanophysics at Keele University and senior author on the study. “It clearly suggests that there’s more to understand about brain neurochemistry than we’d originally imagined.”

Seeing metals at nanoscales

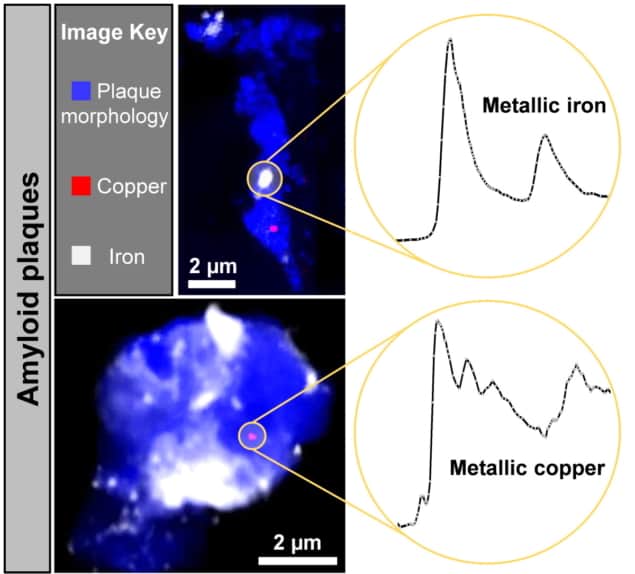

To locate, identify, map and characterize the elemental metal deposits, the researchers obtained high-resolution images and chemically sensitive measurements with a technique called X-ray spectromicroscopy, a non-destructive method that has been used in environmental studies and to analyse synthetic materials at nanometre scales.

In this powerful measurement technique, a circular particle accelerator called a synchrotron generates multi-energy, or polychromatic, X-rays, from which low-energy X-rays are selected and focused into a beam. The focused X-ray beam, only 20 nm in diameter, is then moved across amyloid plaque samples to create a stack of images.

Each image in a stack corresponds to a different X-ray energy. By combining these different images, researchers can obtain absorption spectra from different regions of the amyloid plaques and then analyse the spectra to identify metals.

“With this technique, we can vary the energy of the X-rays and look at the absorption of the X-rays to look at characteristic spectral features of these materials, which will tell us which elements we’re looking at and their oxidation state,” explains Telling.

The researchers can also test the magnetic properties of the samples using circularly polarized X-rays.

Through their experiments, which were performed at the UK’s Diamond Light Source and the US Department of Energy’s Advanced Light Source, the researchers observed nanoscale deposits of elemental copper and iron that were around ten-thousandth the size of a pinhead. This is around half the size of lysosomes, the parts of cells that help break down and remove cellular waste.

What’s next?

The researchers think that the elemental deposits may have been formed during chemical reactions taking place in the amyloid plaques, primarily because the elemental copper and iron appeared next to their oxide forms in the plaques that the researchers tested.

But Telling cautions that there’s much more work to do before they can say anything definitive about the role these metals play in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

“It will take a number of years before we can say categorically whether we see metals in elemental forms just in Alzheimer’s plaques, for example, or if we see this in other areas of tissue as well,” Telling says. “But there’s certainly a possibility that this could indicate that there are some redox [reduction–oxidation] chemical reactions going on in the brain that are even more aggressive than we originally imagined and could be linked to disease progression.”