By Ian Randall

In the modish hunt for exoplanets, the holy grail is discovering such a body within the habitable zone of a star – offering a tantalizing potential for extraterrestrial life. If our solar system is anything to go by, we can expect most planets to form outside of the confines of this zone. What if, however, the habitable zone is really larger than we thought?

This is the idea put forward by Sean McMahon from the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and colleagues in a recent paper – proposing that the existing definition of the habitable zone overlooks the potential for life to survive below the surface of terrestrial planets that currently lie outside the zone’s reach.

The habitable zone around a star is traditionally defined as the thin shell of space in which liquid water may exist on the surface of Earth-like planets. Bringing to mind the old fairy tale of Goldilocks, planets in this region are “just right” – neither so close to the host star that they suffer runaway greenhouse warming, nor so far away that all surface water ends up frozen.

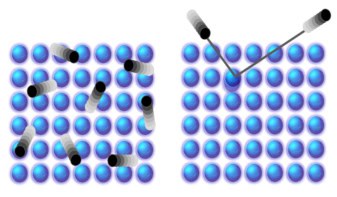

The assumption made here is that the presence of liquid water on a planet’s surface is absolutely necessary if that world is to support life. On the Earth, however, we find many micro-organisms that live beneath the planet’s surface – occupying pores and cracks in rocks at depths of up to several kilometres beneath our feet. Living in aquifers and hydrothermal systems, these creatures form a “deep biosphere”, one which may even rival its surface counterpart in mass. While many of these underground dwellers live on buried photosynthetic matter and dissolved oxidants from above, some are able to live their lives in complete independence of surface conditions. They sustain themselves instead on nutrients and energy from geochemical sources.

So, if life can survive independently at such depths on Earth, why not on other planets too? With this in mind, the researchers propose a new term – the subsurface-habitability zone (SSHZ) – covering the range of distances from a host star at which rocky planets might support life up to a given maximum depth.

In its paper, the team presents a model – which calculates the expected habitable layer within a planet of given size and orbital radius – and results corresponding to bodies similar to Earth, Mars and other known extrasolar planets. Their results show that SSHZs have a significantly larger range than traditional, surface, habitable zones and should incorporate many more planets – even if any such deep biospheres would be hard to detect.