Chanda Prescod-Weinstein reviews Fashion, Faith and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe by Roger Penrose

To truly immerse oneself in Roger Penrose’s Fashion, Faith and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe is to fully experience the agony and joy of the theoretical physicist’s quest to reckon with the problem of quantum gravity. The search for a way to unite quantum mechanics and relativity drives the work of many physicists, especially ambitious and optimistic young PhD students. Indeed, there is something romantic about the effort, like a hero’s quest to make a lasting mark on the field by thinking deeply and then riding home triumphantly with the answer in hand.

The problem of course is that after nearly a century, the task has not only proved theoretically and experimentally insurmountable (so far), but it has also come with difficult sociological challenges. The story of quantum gravity is therefore not only about the joys of mastering difficult calculations, asking deep questions and exploring fantastical possibilities. It is also about wrestling for resources; taking unpopular and sometimes career-ending risks; and struggling to understand independence in the midst of a herd.

The decision by Princeton University Press to publish this work is an interesting one. The text lacks a natural audience, but for those who come to it and are willing to do the hard work of reading it, there are potential rewards. The book is offered as an overview of the boundaries of what we know in high-energy and gravitational physics, with a scientific critique and commentary on the sociological dynamics around these ideas. Penrose takes the view that getting beyond the boundary will require making sure that we are actually at the right one. To that end, he offers protracted semi-technical introductions to string theory, quantum mechanics, modern cosmology and his own pet programme, twistor theory.

Each of these introductions is very evidently biased by Penrose’s own perspective, and by what other practitioners in the field might call his misunderstandings. Fashion is based on a lecture Penrose gave in the early 2000s in which he expressed views that have since been challenged repeatedly by fellow physicists. Unfortunately, the book does not really wrestle with any of those challenges. Instead, Penrose sets up the “fashion”, “faith” and “fantasy” entirely from his perspective, knocks them down and ignores any factors that might upend his logic.

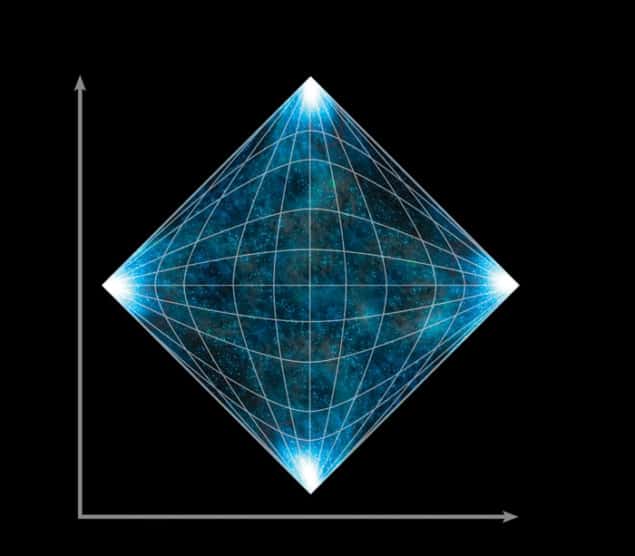

As an elder statesman of the field who has already left a lasting impression, it is possible that Penrose has earned the right to do this. When I was a young and optimistic student of loop quantum gravity who was excited to be seated near him at a dinner, I asked Penrose how he had come up with his majestic space–time diagrams, known as Penrose diagrams. He told me that he needed to draw space–time in order to understand it – that was all. Indeed, the book is replete with phenomenal visual representations of the physics under discussion, a reminder of Penrose’s ability to see and describe physics in a unique way.

A great strength of these discussions is that they include some of the best introductions to difficult topics that can be found in the semi-technical or amateur-oriented literature. For example, Penrose’s discussion of Feynman diagrams is very intuitive. He offers a historic perspective that can only come with having spent decades in the theoretical physics trenches, and his holistic views on the ties between the various branches of physics may help senior undergraduates or beginning graduate students gain some perspective on what they know.

Ultimately, what is most valuable about the book is the excellent example he offers in how to ask questions. He certainly raises more questions than he answers, and I found the answers he provides to be inadequate more than once. For example, Penrose believes that modern cosmology’s reliance on inflationary theory as a building block of our cosmic timeline is overly fantastical. He portrays us cosmologists as uniformly and simply invested in inflation, untroubled by open problems related to it, even though we are all troubled by many of the issues he raises. Despite this, I found that even as I disagreed with Penrose, he forced to me to think, and think deeply, about the fundamental assumptions I have relied upon as a researcher and the axioms I was taught as a student.

While the text has supposedly been made accessible by avoiding the use of differential calculus, in reality, one cannot follow it without knowing the material in a lengthy appendix. Within a few pages, this appendix introduces the concept of fibre bundles, which can be difficult for even a PhD-level physicist to fully wrap their mind around. Penrose’s optimism and expressed desire that the interested amateur will be able to navigate the text is admirable, but on reading, it seems unrealistic. An open admission that this text is intended for readers with a background in physics would have strengthened it. Certainly, such an admission would have shrunk the number of potential purchasers, but it would also have given the author more freedom to make his point.

Readers who struggle to follow the technical prose may, however, still appreciate the sociological commentary. Penrose is right to question the significant impact that the hyper focus on fashionable string theory has had on the physics community. He notes that the pressure to publish or perish and the feedback loop between this pressure and receiving funding is made all the worse by what may have been an excessive emphasis on one approach.

Similarly, questions raised about the faith we have in quantum mechanics are worth thinking through, even though here, again, Penrose refuses to grapple with critiques of his viewpoint. The one-sidedness in the author’s thinking is a general weakness of the book, and this makes it difficult to suggest that a non-expert or student read it without guidance. If one is not expert on the topics discussed, it is possible to be misled by Penrose’s biases. On the other hand, in some sense, this is exactly the phenomenon the text was meant to warn us about.

- 2016 Princeton University Press £19.95/$29.95hb 520pp