Braille is a tactile writing system that helps people who are blind or partially sighted acquire information by touching patterns of tiny raised dots. Braille uses combinations of six dots (two columns of three) to represent letters, numbers and punctuation. But learning to read braille can be challenging, particularly for those who lose their sight later in life, prompting researchers to create automated braille recognition technologies.

One approach involves simply imaging the dots and using algorithms to extract the required information. This visual method, however, struggles with the small size of braille characters and can be impacted by differing light levels. Another option is tactile sensing; but existing tactile sensors aren’t particularly sensitive, with small pressure variations leading to incorrect readings.

To tackle these limitations, researchers from Beijing Normal University and Shenyang Aerospace University in China have employed an optical fibre ring resonator (FRR) to create a tactile braille recognition system that accurately reads braille in real time.

“Current braille readers often struggle with accuracy and speed, especially when it comes to dynamic reading, where you move your finger across braille dots in real time,” says team leader Zhuo Wang. “I wanted to create something that could read braille more reliably, handle slight variations in pressure and do it quickly. Plus, I saw an opportunity to apply cutting-edge technology – like flexible optical fibres and machine learning – to solve this challenge in a novel way.”

Flexible fibre sensor

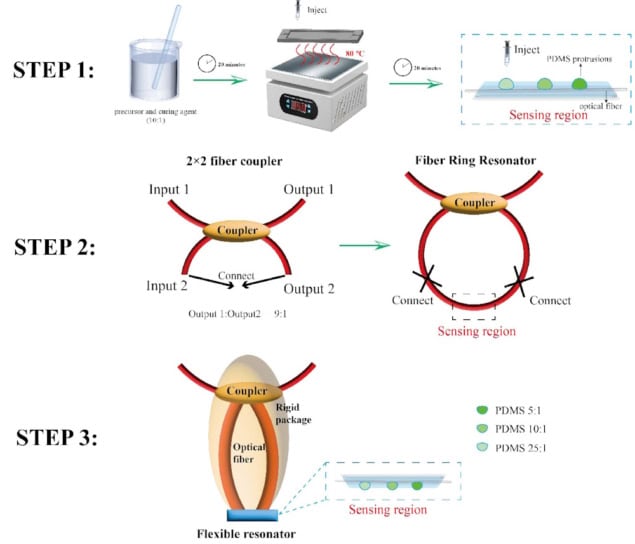

At the core of the braille sensor is the optical FRR – a resonant cavity made from a loop of fibre containing circulating laser light. Wang and colleagues created the sensing region by embedding an optical fibre in flexible polymer and connecting it into the FRR ring. Three small polymer protrusions on top of the sensor act as probes to transfer the applied pressure to the optical fibre. Spaced 2.5 mm apart to align with the dot spacing, each protrusion responds to the pressure from one of the three braille dots (or absence of a dot) in a vertical column.

As the sensor is scanned over the braille surface, the pressure exerted by the raised dots slightly changes the length and refractive index of the fibre, causing tiny shifts in the frequency of the light travelling through the FRR. The device employs a technique called Pound-Drever-Hall (PDH) demodulation to “lock” onto these shifts, amplify them and convert them into readable data.

“The PDH demodulation curve has an extremely steep linear slope, which means that even a very tiny frequency shift translates into a significant, measurable voltage change,” Wang explains. “As a result, the system can detect even the smallest variations in pressure with remarkable precision. The steep slope significantly enhances the system’s sensitivity and resolution, allowing it to pick up subtle differences in braille dots that might be too small for other sensors to detect.”

The eight possible configurations of three dots generate eight distinct pressure signals, with each braille character defined by two pressure outputs (one per column). Each protrusion has a slightly different hardness level, enabling the sensor to differentiate pressures from each dot. Rather than measuring each dot individually, the sensor reads the overall pressure signal and instantly determines the combination of dots and the character they correspond to.

The researchers note that, in practice, the contact force may vary slightly during the scanning process, resulting in the same dot patterns exhibiting slightly different pressure signals. To combat this, they used neural networks trained on large amounts of experimental data to correctly classify braille patterns, even with small pressure variations.

“This design makes the sensor incredibly efficient,” Wang explains. “It doesn’t just feel the braille, it understands it in real time. As the sensor slides over a braille board, it quickly decodes the patterns and translates them into readable information. This allows the system to identify letters, numbers, punctuation, and even words or poems with remarkable accuracy.”

Stable and accurate

Measurements on the braille sensor revealed that it responds to pressures of up to 3 N, as typically exerted by a finger when touching braille, with an average response time of below 0.1 s, suitable for fast dynamic braille reading. The sensor also exhibited excellent stability under temperature or power fluctuations.

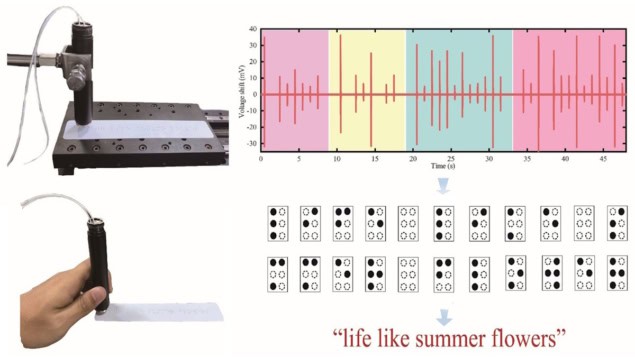

To assess its ability to read braille dots, the team used the sensor to read eight different arrangements of three dots. Using a multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural network, the system effectively distinguished the eight different tactile pressures with a classification accuracy of 98.57%.

Next, the researchers trained a long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network to classify signals generated by five English words. Here, the system demonstrated a classification accuracy of 100%, implying that slight errors in classifying signals in each column will not affect the overall understanding of the braille.

Finally, they used the MLP-LSTM model to read short sentences, either sliding the sensor manually or scanning it electronically to maintain a consistent contact force. In both cases, the sensor accurately recognised the phrases.

Physics in the dark

The team concludes that the sensor can advance intelligent braille recognition, with further potential in smart medical care and intelligent robotics. The next phase of development will focus on making the sensor more durable, improving the machine learning models and making it scalable.

“Right now, the sensor works well in controlled environments; the next step is to test its use by different people with varying reading styles, or under complex application conditions,” Wang tells Physics World. “We’re also working on making the sensor more affordable so it can be integrated into devices like mobile braille readers or wearables.”

The sensor is described in Optics Express.