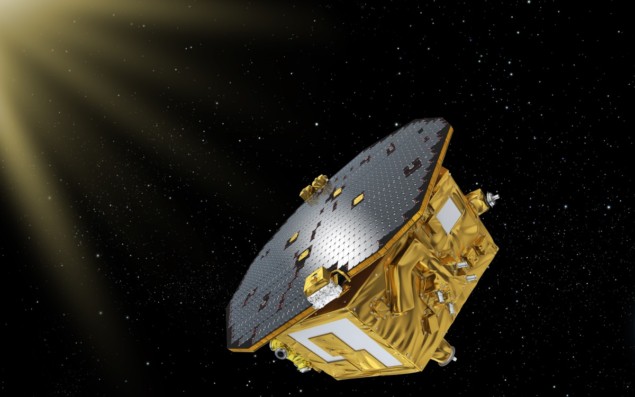

From its orbital worksite 1.5 million kilometres from Earth, the LISA Pathfinder mission has been putting the technology required to build a space-based gravitational wave detector through its paces. In a new study, made using information collected from the satellite, scientists involved in the mission have shown that it can also shed light on another enigmatic astronomical target: interplanetary dust.

By examining data from the spacecraft’s on-board systems, the researchers have been able to pinpoint more than 50 separate instances where LISA Pathfinder “felt” a minuscule jolt as it was hit by a wandering grain of cosmic dust. Through analysis of the collisions, the scientists have even been able to work out the direction on the sky where the dust came from and so uncover clues about the origin of these tiny flecks of Solar System detritus.

The European-led LISA Pathfinder project was launched in 2015 as a test bed for projects like the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna mission, LISA, which is due to lift off in 2034. Once established in orbit, LISA will look for the ripples in the fabric of space–time that propagate across the cosmos when black holes or neutron stars collide. “[LISA] will detect passing gravitational waves by monitoring the distance between widely separated pairs of freely falling objects,” says team member Ira Thorpe of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Launch of LISA Pathfinder probe heralds new era in search for gravitational waves

The freely falling objects in the case of the LISA Pathfinder trial mission are a pair of two-kilogram gold and platinum cubes that float unperturbed within special voids inside the satellite. “A control system monitors the position of the spacecraft relative to the cubes and fires thrusters on the spacecraft to keep the spacecraft from touching the cubes,” explains Thorpe. “The spacecraft is like a shield that flies around the test masses and protects [them] from any external disturbances.”

By combing through the telemetry from LISA Pathfinder’s control system – which recorded how close the cubes got to the interior of the spacecraft and when the thrusters were working – Thorpe and his colleagues were able to spot moments when the satellite was responding to and correcting for the tiny bumps to its exterior from micrometeoroid impacts. “What makes this technique possible is the exquisite precision of LISA Pathfinder’s sensors,” says Thorpe. “A laser interferometer was used to measure the distance between the test masses and the spacecraft with a precision of less than one trillionth of a metre.”

Using computer-modelling methods normally used to unravel gravitational wave signals, the team were able to ascertain the direction the dust grains were coming from when they hit the spacecraft. This information suggests that the bulk of this so-called “zodiacal” dust – which is scattered across our planetary neighbourhood – was deposited by Jupiter-family comets with Halley-type comets possibly adding to the mix as well. “This is entirely consistent with models based on other independent observations,” says Thorpe.

“This is a really interesting study,” says Mark Jones, an expert in the zodiacal dust cloud based at the Open University in the UK. “In particular, [it] provides a novel way to distinguish between various cometary and asteroid dust sources – something which has been a topic of debate for many years.” Jones points out that there is not yet enough data for the study to give high-quality information about the sources of dust, but he says that the “technique appears to be sound and offers a lot of promise”.

Indeed, Thorpe and his colleagues are expecting that the forthcoming LISA mission will also be able to sense these dust impacts while it carries out its main job of hunting gravitational waves. “There will be three spacecraft and hopefully a mission of 10 years, so we will have much more data to work with,” says Thorpe.

- Full details are available on arXiv.