A sensitive new portable device can detect gas molecules associated with certain diseases by condensing dilute airborne biomarkers into concentrated liquid droplets. According to its developers at the University of Chicago in the US, the device could be used to detect airborne viruses or bacteria in hospitals and other public places, improve neonatal care, and even allow diabetic patients to read glucose levels in their breath, to list just three examples.

Many disease biomarkers are only found in breath or ambient air at levels of a few parts per trillion. This makes them very difficult to detect compared with biomarkers in biofluids such as blood, saliva or mucus, where they are much more concentrated. Traditionally, reaching a high enough sensitivity required bulky and expensive equipment such as mass spectrometers, which are impractical for everyday environments.

Rapid and sensitive identification

Researchers led by biophysicist and materials chemist Bozhi Tian have now developed a highly portable alternative. Their new Airborne Biomarker Localization Engine (ABLE) can detect both non-volatile and volatile molecules in air in around 15 minutes.

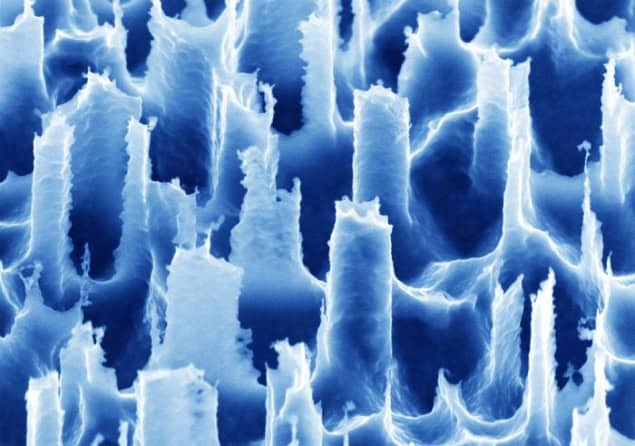

This handheld device comprises a cooled condenser surface, an air pump and microfluidic enrichment modules, and it works in the following way. First, air that (potentially) contains biomarkers flows into a cooled chamber. Within this chamber, Tian explains, the supersaturated moisture condenses onto nanostructured superhydrophobic surfaces and forms droplets. Any particles in the air thus become suspended inside the droplets, which means they can be analysed using conventional liquid-phase biosensors such as colorimeteric test strips or electrochemical probes. This allows them to be identified rapidly with high sensitivity.

Tiny babies and a big idea

Tian says the inspiration for this study, which is detailed in Nature Chemical Engineering, came from a visit he made to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in 2021. “Here, I observed the vulnerability and fragility of preterm infants and realized how important non-invasive monitoring is for them,” Tian explains.

“My colleagues and I envisioned a contact-free system capable of detecting disease-related molecules in air. Our biggest challenge was sensitivity and initial trials failed to detect key chemicals,” he remembers. “We overcame this problem by developing a new enrichment strategy using nanostructured condensation and molecular sieves while also exploiting evaporation physics to stabilize and concentrate the captured biomarkers.”

The technology opens new avenues for non-contact, point-of-care diagnostics, he tells Physics World. Possible near-term applications include the early detection of ailments such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which can lead to markers of inflammation appearing in patients’ breath. Respiratory disorders and neurodevelopment conditions in babies could be detected in a similar way. Tian suggests the device could even be used for mental health monitoring via volatile stress biomarkers (again found in breath) and for monitoring air quality in public spaces such as schools and hospitals.

“Thanks to its high sensitivity and low cost (of around $200), ABLE could democratize biomarker sensing, moving diagnostics beyond the laboratory and into homes, clinics and underserved areas, allowing for a new paradigm in preventative and personalized medicine,” he says.

Widespread applications driven by novel physics

The University of Chicago scientists’ next goal is to further miniaturize and optimize the ABLE device. They are especially interested in enhancing its sensitivity and energy efficiency, as well as exploring the possibility of real-time feedback through closed-loop integration with wearable sensors. “We also plan to extend its applications to infectious disease surveillance and food spoilage detection,” Tian reveals.

Electrochemical cell could detect airborne SARS-CoV-2

The researchers are currently collaborating with health professionals to test ABLE in real-world settings such as NICUs and outpatient clinics. In the future, though, they also hope to explore novel physical processes that might improve the efficiency at which devices like these can capture hydrophobic or nonpolar airborne molecules.

According to Tian, the work has unveiled “unexpected evaporation physics” in dilute droplets with multiple components. Notably, they have seen evidence that such droplets defy the limit set by Henry’s law, which states that at constant temperature, the amount of a gas that dissolves in a liquid of a given type and volume is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas in equilibrium with the liquid. “This opens a new physical framework for such condensation-driven sensing and lays the foundation for widespread applications in the non-contact diagnostics, environmental monitoring and public health applications mentioned,” Tian says.