A new measurement by CERN’s ATLAS Collaboration has strengthened evidence that the masses of fundamental particles originate through their interaction with the Higgs field. Building on earlier results from CERN’s CMS Collaboration, the observations suggest that muon–antimuon pairs (dimuons) can be created by the decay of Higgs bosons.

In the Standard Model of particle physics, the fermionic particles are organized into three different generations, broadly in terms of their masses. The first generation comprises the two lightest quarks (up and down), the lightest lepton (the electron) and the electron neutrino. The second includes the strange and charm quarks, the muon and its neutrino; and the third generation the bottom and top quarks, the tau and its neutrino. In terms of the charged fermions, the top quark is nearly 340,000 times heavier than the lightest – the electron.

All of the quarks and leptons have both right- and left-handed components, which relate to the direction of a particle’s spin relative to its direction of motion (right-handed if both directions are aligned; left-handed if they are anti-aligned).

Right- and left-handed particles are treated the same by the strong and electromagnetic forces, regardless of their generation in the Standard Model. The weak force, however, only acts on left-handed particles.

Flipping handedness

In the 1960s, Steven Weinberg uncovered a theoretical solution to this seemingly bizarre asymmetry. He proposed that the Higgs field acts as a bridge between each particle’s left- and right-handed components, in a way that respects the Standard Model’s underlying symmetry. This interaction causes the particle to constantly flip between its two components, creating a resistance to motion that can be perceived as mass.

However, this deepens the mystery. According to Weinberg’s theory, higher-mass particles must interact more strongly with this Higgs field – but in contrast, the strong and electromagnetic forces can only differentiate between these particles according to their charges (colour and electrical). The question is how does Higgs field can distinguish between particles in different generations if their charges are identical?

Key to solving this mystery will be to observe the decay products of Higgs bosons with different interaction strengths. For stronger interactions, corresponding to heavier generations, these decays should become far more likely.

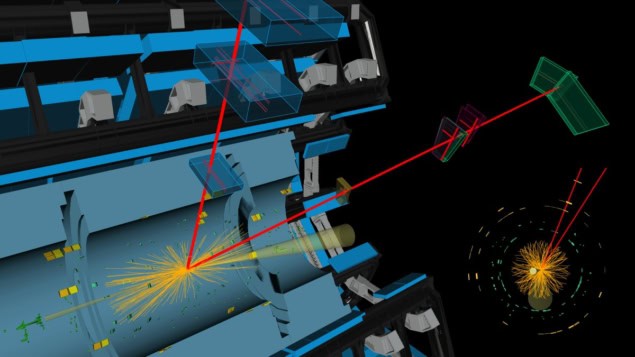

In 2022, both the ATLAS and CMS collaborations did just this. Through proton–proton collision experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the groups independently observed Higgs bosons decaying to tau–antitau pairs. This relatively common process occurred at the same rate as predicted by theory.

Rare decay

A year earlier, similar experiments by the CMS collaboration probed the second generation by observing muon–antimuon pairs from the decays of Higgs bosons. This rarer event occurs in just 1 in 5000 Higgs decays.

How a next-generation particle collider could unravel the mysteries of the Higgs boson

In their latest study, the ATLAS collaboration have now reproduced this CMS result independently. They collided protons at about 13 TeV and observed muon–antimuon pairs in the same range of energies predicted by theory.

Through the improvements they offer on the earlier CMS analysis, these new results bring dimuon observations to a statistical significance of 3.4σ. This is well below the 5σ standard required for the observation to be considered a discovery, so more work is needed.

The research could also provide guidance in the search for much rarer Higgs interactions that involve first-generation particles. This includes decay electron–positron pairs, originating from Higgs bosons which decay in just 1 in 200 million cases.

The research is described in Physical Review Letters.