Physicists in Netherlands and Japan are the first to flip the value of a magnetic memory bit by firing a very short pulse of circularly-polarized laser light at it. Unlike other magneto-optic data storage systems, no external magnetic field was required to flip the bit, which meant that its value could be changed about 50 thousand times faster than the fastest conventional memory. The result could lead to the development of low-cost and ultrafast all-optical magnetic hard disk drives (Phys. Rev. Lett. 99 047601 ).

Most computers store data on magnetic hard disk drives, in which the direction – “up” or “down” – of the magnetic moments in a small region of the disk corresponds to a binary bit. Data are read by a magneto-resistance element and written by heating the bit with a laser and then flipping the moments with a magnetic field pulse from a tiny coil.

The cost and complexity of hard drives could be reduced significantly if data could instead be read and written using light alone. While some commercial hard drives now use light to read data from magnetic bits, a technique for writing data using only light had remained elusive.

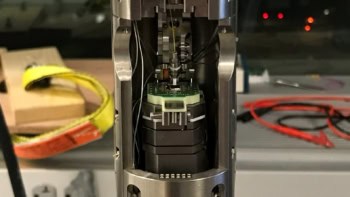

Now, Theo Rasing and colleagues at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands along with researchers at Nihon University in Japan have shown that a single laser pulse can flip the magnetization of a 5 µm spot on a thin magnetic film from up to down and vice versa – without the need for an external magnetic field.

The pulse was only 40 fs (10-15 s) long – much shorter than the magnetic field pulses used in hard drives, which cannot be made much shorter than about 2 ns. Indeed, the 40 fs switching time had been thought to be impossible because in 2004, a 2 ps lower limit on controlled magnetic switching had been established by another team of physicists.

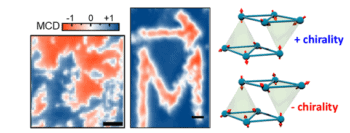

The laser pulse was circularly polarized, which means that it creates an intense but highly localized magnetic field within the material. The pulse was switched between two polarization states, which flips the direction of the field.

The researchers did their experiments on an alloy of gadolinium, iron and cobalt, which is used widely in magneto-optic data storage devices. The team is now checking to see if the switching occurs in materials with higher coercivity, which could allow an all-optical memory to achieve the same storage density as a conventional hard drive.

Rasing has patented the write process and he is confident that it will be commercialized. However, he admits that anyone wanting to build a hard drive using the technology would have to overcome the significant challenge of how to build a tiny laser that can also produce an intense pulse of circularly-polarized light that can be focussed down to a spot 50 nm in diameter, which is much smaller than the wavelength of the laser light. “But these are solvable problems,” he says.