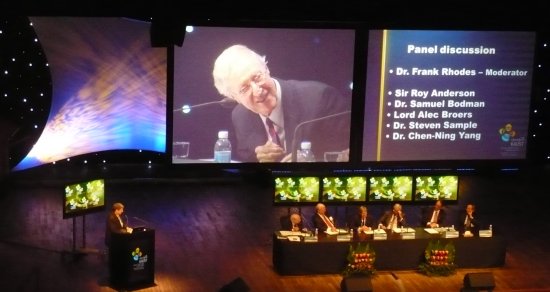

Who’s who of science and engineering

By Matin Durrani

This will be my last blog entry during my visit to KAUST — Saudi Arabia’s new research university, which opened on Wednesday.

The highlight of yesterday was the inaugural symposium entitled “Sustainability in a changing climate”, which is a key part of KAUST’s mission.

First to speak was George W Bush’s former energy secretary Samuel Bodman, who outlined four priorities for tackling climate change — increased energy efficiency, new-generation nuclear reactors, growing use of renewables and advanced biofuels, and better exploitation of fossil fuels such as clean coal.

Next up was Alec Broers, former president of the UK’s Royal Academy of Engineering, who discussed the importance of engineers in sustainability. “Scientists have sounded the alarm. Engineers need to find the solution”; he said. Mind you, he would say that — Broers trained as a physicist at the University of Melbourne before a career in engineering.

Madly perfect?

After words from a couple of other heavyweights — Imperial College rector Sir Roy Anderson and University of Southern California president Steven Sample — on to the stage came Chen Ning Yang, the 87-year-old physicist who shared the 1957 Nobel prize with Tsung-dao Lee.

Remarkably young looking, Yang stressed the importance of basic research, pointing out how quantum theory in the early decades of the 20th century led to semiconductors, which led to transistors, which led to chips — without which computers, TV and the rest of modern life — would not exist.

Yang’s view, widely held, is that basic research leads to applied research in a linear path. Actually, things are a lot more complicated than that, but cosily ensconsed in my leather seat high up in KAUST’s vast auditorium, I kept quiet.

As I stepped out of the symposium into the warm evening air, the angular, university buildings were lit up beautifully and a troupe of singers could be heard singing in the main square where small tables lay with cold drinks. Guests pressed forwards to the music, and there, above the scene, as if by arrangement, was a half-crescent moon, the symbol of Islam. Like KAUST itself, the whole scene seemed madly perfect — and almost too good to be true.