Proton energies achievable in laser accelerators could be tripled by using specially designed micronozzle targets, according to computer simulations done by physicists in Japan and India. In their design, the electric field generated in the micronozzle would be funnelled towards the outgoing protons, allowing the acceleration to proceed for much longer. The researchers believe that the research could be useful in nuclear fusion, hadron therapy and materials science.

Conventional accelerators use oscillating electric fields to drive charged particles to relativistic speeds. The Large Hadron Collider at CERN, for example, uses radio-frequency oscillations to achieve proton energies of nearly 7 TeV.

These accelerators tend to be very large, which limits where they can be built. Laser acceleration, which involves using high-energy laser pulses to accelerate charged particle, offers a way to create much more compact accelerators.

Crucial to inertial confinement

Laser acceleration is crucial to inertial confinement fusion, and high energy proton beams produced by laser accelerators are used in scientific laboratories for a variety of scientific applications including laboratory astrophysics.

The standard techniques for laser acceleration involve firing a laser pulse at a proton target surrounded by metal foil. Solid hydrogen only exists near absolute zero, so the proton target can be a hydrogen-rich compound such as a hydride or a polymer. The femtosecond laser pulse concentrates a huge amount of energy into a tiny area and this instantly turns the target into a plasma. The light’s oscillating electromagnetic field drives electrons through the plasma, leaving behind the much heavier ions and creating a huge electric field that can accelerate protons.

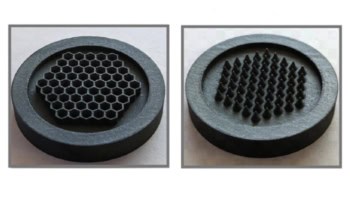

In the new work, physicist Masakatsu Murakami and colleagues at the University of Osaka in Japan, together with researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad, used computer modelling to examine the effect of changing the shape of the metal surrounding the target from a simple planar foil to a two-headed nozzle, with the target placed at the narrowest point. During the first stage of the acceleration process, the wide head of the nozzle behaves like a lens, concentrating the electric field from a wide area to produce an enhanced flow of hot electrons towards the centre. This electric current on the nozzle enhances ablation of protons from the hydrogen rod, kicking them forward into the vacuum.

“Just like a rocket nozzle”

Subsequently, the electrons keep moving through the “skirt” of the nozzle, creating a powerful electric field that, owing to the nozzle’s shape, remains focused on the accelerating proton pulse as it travels away into the vacuum. “With the single hydrogen rod and the single foil, the protons are accelerated only during the laser illumination,” explains Murakami. “However, interestingly with the micronozzle target, the acceleration keeps going even after the laser pulse illumination…Most of the plasma expands in a small volume together with the protons – just like a rocket nozzle,” he says. Whereas the standard proton energies achievable with a laser accelerator today are around 400 MeV, the researchers estimate that their micronozzle design could allow energies into the gigaelectronvolt regime without changing anything else.

Murakami has been studying nuclear fusion for 40 years and believes that “this method will be used for fast ignition of laser fusion”. However, he says, its potential uses go far beyond this. Proton beam therapy generally uses protons with energies of 200–300 MeV to treat cancer by delivering a high dose of radiation to the tumour and a much lower dose to surrounding healthy tissue. “Even higher energy is required to target cancers that are located in deeper parts of the body,” he says. The technique could also be useful for materials science techniques such as proton radiography or for simulation of the physics of astrophysical objects such as neutron stars. “I’m planning to do proof of principle experiments in the near future,” says Murakami.

Accelerator physicist Nicholas Dover of Imperial College London describes the work as “very interesting,” adding, “This target that they propose is a very complex thing to make. It would be a big project for a target fabrication lab to generate something like this – it’s not something we just cook up in our lab. Having these numerical optimizations is really helpful for us.” He notes, however, that one reason accelerator physicists often use planar targets (essentially pieces of kitchen foil) is the need to replace them in every shot. In scientific applications, this may not matter, he says. Applications in fields like medicine, however, would probably require the development of mass production facilities to fabricate the targets economically.

The research is described in Scientific Reports.