When we look up at the Moon from our Earthly vantage point, we see a familiar face of shadowed craters and bright ridges. But nowadays, with the aid of satellites and telescopes, we’re also able to look beyond that well-known visage and see our nearest neighbour in a different light. Sarah Tesh picks some of her favourite alternative views of the Moon.

A familiar face

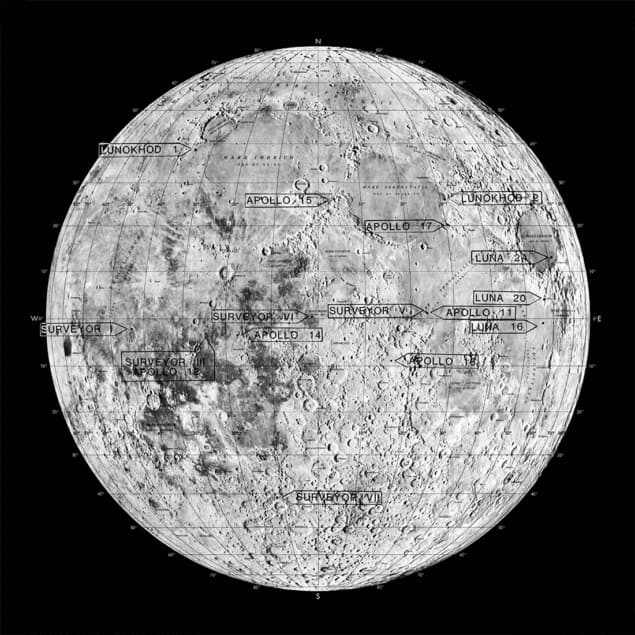

Until this year (see “Exploring the far side“), humankind had only ever landed spacecraft on the near side of the Moon – the side that is tidally locked to always face Earth. A total of 20 craft have touched down on this familiar grey visage – including the six Apollo manned missions – though many others have intentionally (and unintentionally) crashed into it. From Earth it is possible to see the Apollo landing sites, rover tracks and leftover experiments. Indeed, our constant neighbour is littered with more than 187 tonnes of artificial objects, ranging from the remains of rockets, spacecraft and the Apollo ascent and descent stages, to Apollo’s commemorative plaques, US flags and even golf balls.

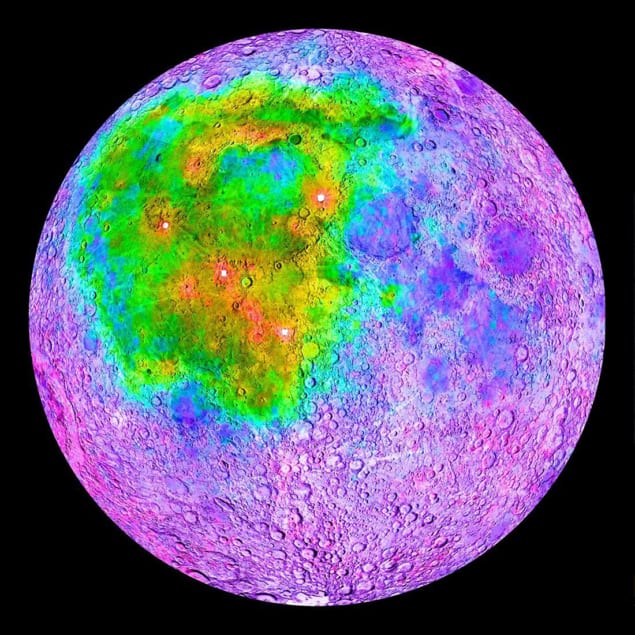

Lunar highs and lows

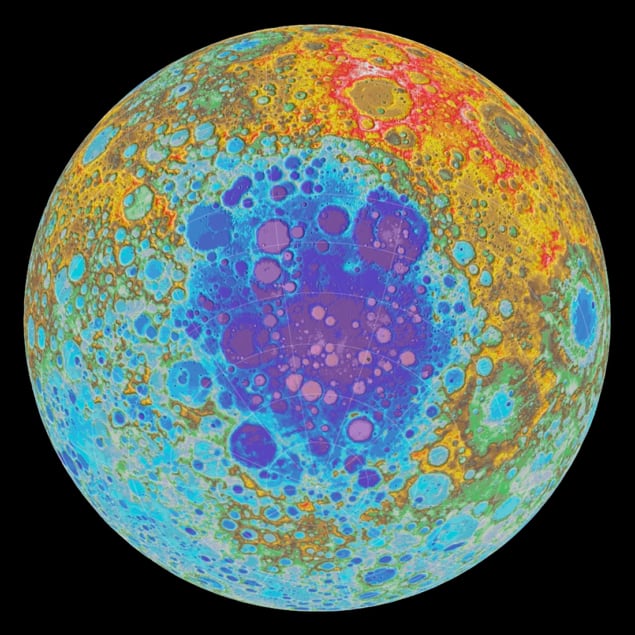

The Moon’s largest observed impact structure is the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin – a region of low altitude roughly 2500 km in diameter, depicted by blues and purples in this topographic map. The feature stretches between the south pole and the Aitken crater on the far side of the Moon. It boasts the Moon’s deepest craters, reaching lows of around –8 km, while the highest elevations (red and white) are within the mountains to the north-east reaching more than 8 km. Although scientists have shown that SPA is the oldest impact basin on the Moon, we do not know its age or what impact created it. Its shadowed areas have potentially useful deposits of hydrogen or water.

Ebb and Flow

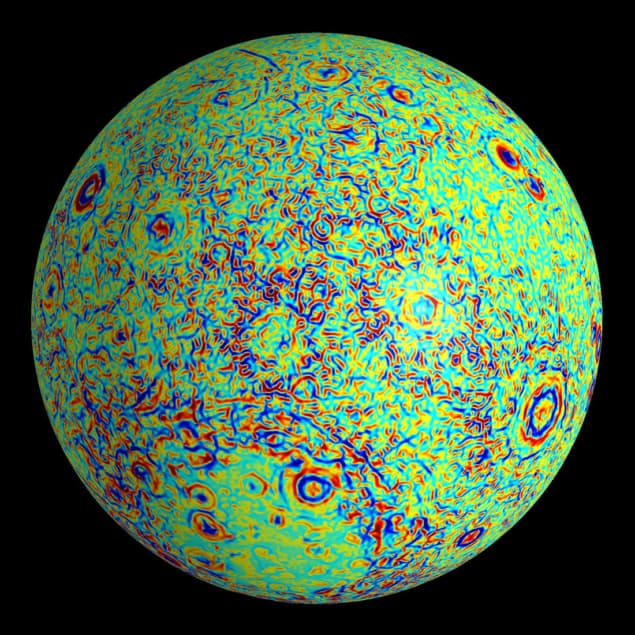

In 2012 NASA’s two Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) spacecraft – Ebb (GRAIL-A) and Flow (GRAIL-B) – produced the most detailed lunar gravity map to date (shown). Like the Earth-orbiting GRACE missions, GRAIL measured the Moon’s gravity by tracking the distance between Ebb and Flow using microwaves – a distance that altered depending on the strength of the gravitational field. The resulting data have provided scientists with clues to the Moon’s interior, revealing, for example, that the crust is less dense than originally thought, and that there may be stable lava tubes beneath the lunar surface.

KREEP on tracking

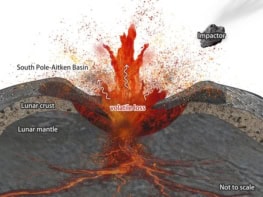

KREEP is lunar rock containing potassium, rare earth elements and phosphorus, and was some of the last material to solidify when the Moon cooled from its molten state. Scientists assumed it was evenly distributed, sandwiched between the lunar crust and mantle. However, in 1998–1989, NASA’s Lunar Prospector mapped the gamma-ray emissions of the Moon, looking for radioactive thorium – a common companion of KREEP. Thorium, and thus KREEP, appears concentrated in the Imbrium basin on the near side (green-white), and, to a lesser extent, in the South Pole-Aitken Basin on the far side. The unevenness is assumed to be related to the Moon’s asymmetric volcanism.