With the 2019 Nobel Prize for Physics due to be announced on Tuesday 8 October, Physics World journalists pick their favourite Nobel awards from the past. Here Matin Durrani argues the case for the 1915 prize for X-ray diffraction

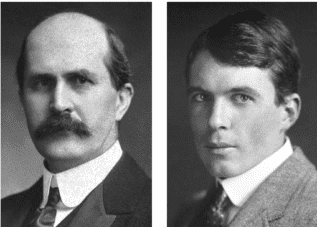

I love the 1915 Nobel Prize for Physics because it was so simple and yet so profound. It was awarded to William Henry Bragg and his son William Lawrence Bragg for realising that X-rays can be used to determine the structure of crystals. It’s an idea so straightforward that it features on many school science syllabuses – and how often can you say that about other Nobel prizes?

The pair famously showed that X-rays of wavelength λ fired at an angle θ through a crystal create bright spots on a photographic plate, according to the famous Bragg equation nλ=2dsinθ, where d is the distance between the crystal planes.

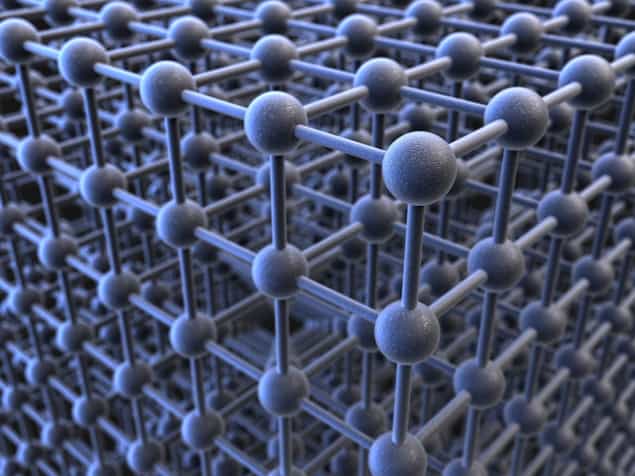

The prize therefore revealed that substances such as sodium chloride don’t contain molecules of NaCl (as had been thought) but sodium and chlorine ions arranged in a regular, geometric structure.

The Braggs’ work in other words opened the door to the modern science of crystallography, which has revolutionzed drug discovery and materials science. Without X-ray diffraction, we’d never have worked out the structure of DNA.

It’s also my favourite prize because it’s a beautiful mixture of fundamental scientific principles, bringing in wave-particle duality, geometrical reasoning, crystal structure and simple mathematics.

And it’s a supremely practical prize too. The Braggs used photographic plates to record their diffraction spots, but the desire to detect the diffracted X-rays with greater and greater precision and sensitivity have led to a myriad of clever detection technologies. Crystallography these days is a massive endeavour, spawning advanced computational techniques and more than 50 synchrotron-radiation sources around the world.

I also love this prize because it’s unique for Nobel watchers. It was the first time a father-and-son pair won a Nobel award for work done together, while Lawrence Bragg is still the youngest person ever to win a Nobel Prize for Physics, being just 25 at the time. Sadly, he heard he’d won just after news came through of his brother being killed serving at Gallipoli during the First World War. There’s also a whole side story about why his father didn’t fully recognise his son’s contributions at the time, which only goes to show how science is and always has been about the people as much as the prizes themselves.

Physics World‘s Nobel prize coverage is supported by Oxford Instruments Nanoscience, a leading supplier of research tools for the development of quantum technologies, advanced materials and nanoscale devices. Visit nanoscience.oxinst.com to find out more.