Tiny traces of food left in ancient clay pots can now be used to date archaeological objects thanks to a novel combination of NMR spectroscopy and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS). The new technique, developed by researchers at the University of Bristol, UK, overcomes previous challenges associated with dating pottery from the prehistoric era.

All living organisms absorb radioactive 14C from the atmosphere. Once an organism dies, radioactive decay causes the amount of this isotope present in its body to decrease at a known rate. Measuring the residual levels of 14C in an object made from formerly-living materials therefore enables scientists to determine how old it is.

AMS radiocarbon dating is one of the most widely-employed methods for estimating the age of archaeological objects up to 50 000 years old. It is mainly applied to samples of charred plant remains and bone collagen, and its adoption has transformed not only archaeology but also many other research disciplines, including climate science. However, objects primarily made from non-living materials, such as clay pots, are far harder to date using AMS – a distinct disadvantage, since pieces of pottery, or sherds, are among the artefacts most commonly recovered from archaeological sites.

Analysing individual fatty acids in food residues

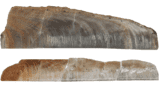

A team led by Richard Evershed has now overcome this problem by analysing food residues that have been absorbed into (and are thus protected by) the clay matrix in pottery. These residues are typically left behind by cooking meat or milk, and they contain high amounts of palmitic (C16:0) and stearitic (C18:0) fatty acids. Indeed, these carbon-bearing compounds are often present in concentrations as high as milligrams per gram of clay.

The researchers isolated the fatty acids by cleaning sherds of cooking pots and then grinding them to a powder, which opens up the surface where the fatty materials (lipids) are preserved. Next, they extracted the lipids with organic solvents and separated the individual compounds in them using preparative capillary gas chromatography.

Evershed and his team checked the purity of their compounds using high-field NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry techniques before placing them in a tin capsule and burning them to make a graphite target. They then transferred this target to an accelerator mass spectrometer and used the instrument (which the lab acquired in 2016) to count the number of 14C atoms within the target. “Bringing together the state-of-the-art NMR to check the purity of the isolated compound and the latest AMS instrument was the major step forward that made these measurements possible,” Evershed says.

Neolithic vessels

The first samples Evershed’s team studied came from Neolithic vessels unearthed at archaeological sites in Somerset, UK; the World Heritage site of Çatalhöyük in Anatolia, Turkey; Lower Alsace in France; and Takarkori in the Sahara region of southwest Libya. Previous dating efforts based on pottery styles suggested that these vessels range in age from around 5500 to over 8000 years old, and the team found that their measurements agreed with these earlier estimates – at least to within a few decades.

Spurred on by this result, the team then analysed a collection of pottery recently excavated by workers from the Museum of London Archaeology in advance of building works there. These samples, which include 436 fragments from at least 24 different bowls, cups and pots, were thought to come from the Early Neolithic period, but their exact age was unknown.

Radiocarbon measurements on milk fats in these vessel fragments revealed that the pottery was 5500 years old. “The results indicate that the area around what is now Shoreditch High Street was already being used at this time by established farmers who ate cow, sheep or goat dairy products as a central part of their diet,” Evershed explains. “These people were likely to have been linked to the migrant groups who were the first to introduce farming to Britain from Continental Europe around 4000 BCE – just 400 years earlier.”

First technique to directly date pottery

Pottery was invented in the late Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million years BCE – 9700 BCE) and was an important factor in the development of food processing, Evershed says. Current techniques for dating it often depend on a careful examination of the object’s style and decorative features. However, this “typology” method provides only a crude estimate of a pot’s age – especially for earlier samples, which tend to be rather plain. Another method, known as association, relies on carbon-dating organic materials (such as charcoal, bone or seed) found lying next to the pottery and using the results to estimate the age of the pot itself. Again, this method is not very accurate, and is prone to errors.

The best method, Evershed says, is to date something from the pots themselves. Other researchers have previously done just that, by dating carbonized materials on the artefacts’ surfaces. However, Evershed notes that these residues are more easily contaminated by their environment than residues embedded within the clay.

Stalagmites boost precision of carbon dating over 54,000 years

“Our new technique is the first to date pottery directly,” he tells Physics World. “And since we are looking at fat residues, we can connect the date of these to food procurement practices. For example, dating milk residues form prehistoric sites gives us an insight into early animal management practices.”

Anchoring “floating chronologies”

Members of the Bristol team, who report their work in Nature, now plan to investigate whether they can apply the technique to other fatty residues such as plant oils or beeswax. Another possibility would be to use it to date mummies, which contain lipids in their soft tissues and bandaging. A third application might involve dating archaeological bones, as these also contain lipids.

“The importance of this advance to the archaeological community cannot be overstated,” Evershed says. While pottery typology makes it possible to arrange objects in chronological order according to their decorative characteristics, he points out that these chronologies are hard to pin down to specific calendar dates. “Our technique allows us to anchor these ‘floating chronologies’ in real calendric time and assign a proper date to them,” he says.