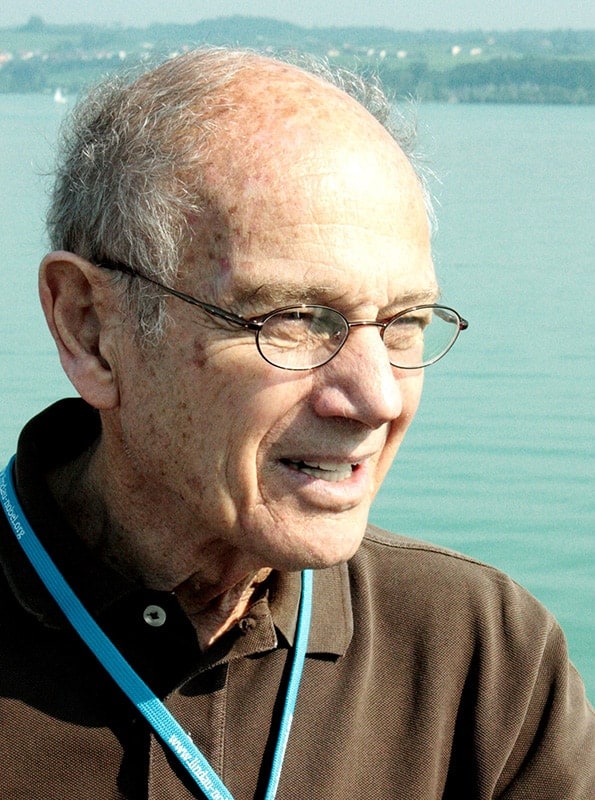

American nuclear-physicist James Cronin, who shared the 1980 Nobel Prize for Physics with Val Fitch, died on 25 August, at the age of 84. Cronin and Fitch – who died in February last year – were awarded the prize for their 1964 discovery that decaying subatomic particles called K mesons violate a fundamental principle in physics known as “CP symmetry.” The research pointed towards a clear distinction between matter and antimatter, helping to explain the dominance of the former over the latter in our universe today.

Born in Chicago, Illinois, on 29 September 1931, Cronin completed his BSc in 1951 at the Southern Methodist University in Dallas, where his father taught Latin and Greek. Cronin moved to the University of Chicago, where he graduated with a PhD in physics in 1955. While there, Cronin benefited from being taught by stalwarts of the field, including Enrico Fermi, Maria Mayer and Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar.

After his doctorate, Cronin worked as an assistant physicist at the Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) until 1958, when he joined the faculty at Princeton University, where he remained until 1971. He then returned to the University of Chicago to become professor of physics. Cronin met Fitch during his time at BNL and it was Fitch who brought him to Princeton. While there, the duo aimed to verify CP symmetry using BNL’s Alternating Gradient Synchrotron (AGS) by showing that two different particles did not decay into the same products.

Verified violation

They planned on doing this by colliding proton beams into a metal target to produce many millions of short-lived and long-lived K mesons. The former would always decay into two pi mesons, while the latter would not. Instead, to their surprise, they spotted a “suspicious-looking hump” in the data, which showed that, on occasion (in 0.2% of the cases), the long-lived variety also decays into two pi mesons, thereby violating CP symmetry.

In recent years, Cronin was instrumental in the development of the Pierre Auger Project, which he conceptualized in 1992 with fellow physicist Alan Watson. The $50m cosmic-ray observatory is based in Argentina, and is designed to pick up ultra-high-energy cosmic rays as they travel at near-light speeds through the Earth’s atmosphere, producing “air showers” of other particles as they interact with atmospheric nuclei. It is currently the world’s largest cosmic-ray detector, with a 3000 km2 collecting area. Despite the fact, the observatory announced in December last year that it is set for a $14m upgrade, which will allow for more precise measurements of the mass of particles that make up cosmic rays, as well as trying to pinpoint their original source.