It’s a mugs game, predicting who will win the Nobel Prize for Physics. Indeed, in the decade or so that I have engaged in such tomfoolery I have only been right twice. And those were pretty obvious – the 2013 prize to François Englert and Peter Higgs for the theoretical discovery of the Higgs boson and the 2017 prize to Rainer Weiss, Barry Barish and Kip Thorne for decisive contributions to the observation of gravitational waves.

I believe that the beauty of the Nobel prizes is that they often come out of the blue, honouring important research done long ago or work that you simply didn’t realize was extremely important.

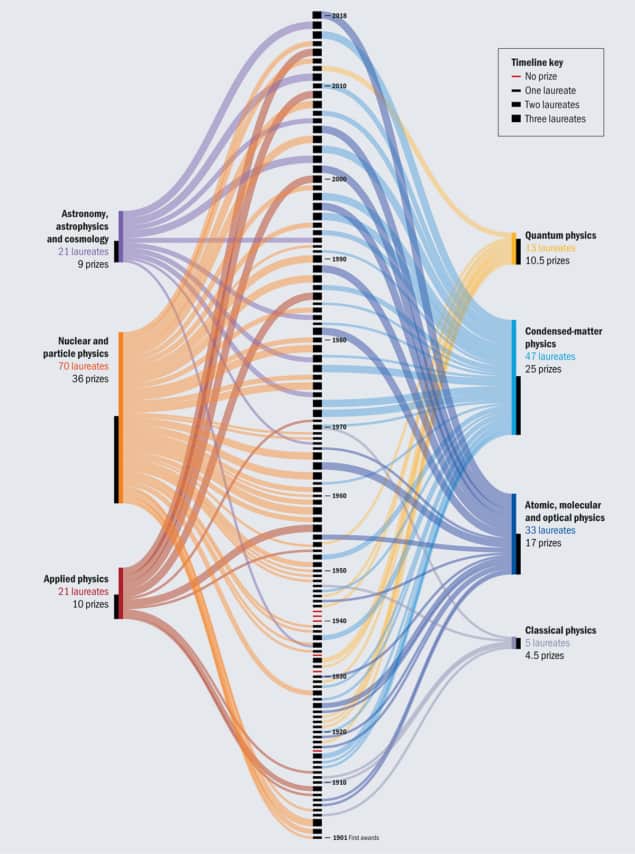

But I’m not giving up on making predictions quite yet, and I have recently updated an infographic we first published in 2014 that illustrates the subject areas of all the physics Nobel prizes since 1901. If you look at each subject area, it appears that subsequent prizes are separated by gaps of about 5-10 years.

If we had looked at the infographic this time last year, we would have been struck by the fact that there had not been a prize for atomic, molecular and optical physics in over ten years – so one should be due. Sure enough, the 2018 prize went to Arthur Ashkin, Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland for their “ground-breaking inventions in the field of laser physics”.

On that basis the official Physics World prediction is that this year’s prize will be awarded for work done in the foundations of quantum physics, a topic that has not garnered a prize since 2012. But who will be making the trip to Stockholm in December?

Our top pick is a prize shared by Alain Aspect, John Clauser and Anton Zeilinger for their work on testing Bell’s inequalities. Back in 2010 the trio bagged the Wolf Prize in Physics for this work – and this is often a harbinger of Nobel glory.

Our second pick is a quantum-information prize to Peter Shor, Gilles Brassard and Charles Bennett. Brassard and Bennett could share half the prize for developing quantum cryptography, while Shor would get the other half for creating his eponymous factoring algorithm for quantum computing. This prize would make it two prizes in a row for Canadian physicists – first Strickland and then Brassard.

Another possibility is a prize to Peter Zoller and Ignacio Cirac for their contributions to the development of schemes for processing quantum information. In particular, the duo published a ground-breaking paper in 1995 describing how a quantum computer could be implemented using cold trapped ions. This paper inspired David Wineland and colleagues to very quickly build such a device and Wineland went on to share the 2012 Nobel prize for his contributions to the control of quantum systems.

Slow light

Beyond quantum information, another longstanding prediction of mine is a prize to Lene Hau for her work on using ultracold gases to slowdown and even stop light. This is something that has already been useful for transferring quantum information from light to matter and then back again.

Finally, and going out on a limb. My final prediction is inspired by the popularity of a recent news story about the non-Abelian Aharonov-Bohm effect. I would be very pleased to see next week’s prize go to Yakir Aharonov and Michael Berry for their work on geometric phases in quantum mechanics.

Physics World‘s Nobel prize coverage is supported by Oxford Instruments Nanoscience, a leading supplier of research tools for the development of quantum technologies, advanced materials and nanoscale devices. Visit nanoscience.oxinst.com to find out more