New coating materials that could help cool buildings in the summer, and then change their optical and thermal properties in the winter to keep the same buildings warm, have been created by researchers in the US. The polymer-based materials could also allow daylight to illuminate building interiors.

The energy use of a building can be reduced by coating its exterior with a smart material that reflects sunlight and emits heat in the summer – but can then be switched in the winter to absorb sunlight and be a poor emitter of heat. The challenge for material scientists is to create practical materials that fit this bill.

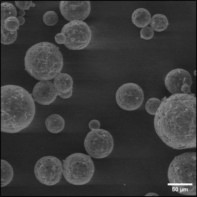

Now, Yuan Yang and colleagues at Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science in New York City have created such materials using porous polymer coatings (PPCs). These are synthetic materials that can adsorb and desorb a wide range of compounds. Their unique properties – including interconnected pore structures, large surface areas, and small pore sizes – make them suitable for many industrial applications. In particular, the variable optical and structural properties of PPCs have found wide uses in coatings for optical and thermal management.

Radiative cooling

PPCs that reflect sunlight and are good emitters of infrared radiation (heat) have proven effective for radiative cooling. On the other hand, PPCs that reflect sunlight but are thermally transparent (are poor infrared emitters) have found use as covering layers for radiative coolers.

The optical properties of PPCs can be tuned by controlling the amount of moisture present in the pores of the material. A similar effect occurs in paper – dry paper has pores filled with air that scatter and reflect light, making the surface appear white. When wet, however, paper is translucent, because the pores are filled with water. This change is a result of the close match between the refractive indices of the material and water, which reduces light scattering within paper.

The newly developed PPCs use this effect to switch between opaque and translucent states for solar radiation. Yang and colleagues have also extended the concept to long-wavelength infrared radiation (LWIR) to modulate the heat radiated by objects.

Similar refractive indices

This was done using the closeness in refractive indices of fluoropolymers (about 1.4) and typical alcohols (about 1.38). Specifically, white poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropene) PPCs become transparent upon wetting with isopropanol. This results in large transmittance changes for solar radiation (a ΔTsol of about 0.74, or more than a factor of six increase in transmittance) and visible light (ΔTvis of about 0.80). Similar changes were also observed for other PPCs, such as polytetrafluoroethene, ethyl cellulose, and polyethylene(PE).

Cool polymer paint saves on air conditioning

Furthermore, the research group showed a decrease in the transmittance of LWIR when thermally transparent PE PPCs were wetted with IR-emissive alcohols. The contrasting transmittances (ΔTLWIR of about –0.64) and (ΔTsol of about 0.33) for PE PPCs suggest potential applications for dynamic switches that could make an icehouse turn into a greenhouse. The observed optical switching was achieved in about 1 min and remain unchanged even after 100 wet-dry cycles.

The research is described in Joule.