By Matin Durrani

Here in the Physics World office our attention was caught last week by a story in the Times Higher Education. It reported on a lecture given by Simon Singh at the 2:AM conference in Amsterdam, in which the broadcaster, author and former particle physicist criticized some projects that are designed to boost the public’s interest in science, but which, he feels, are not value for money.

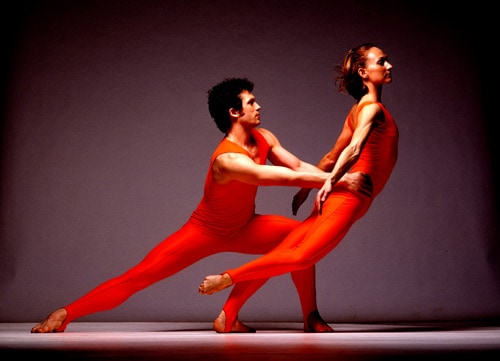

The story mentioned several projects facing Singh’s ire, one of which was the 2005 dance Constant Speed that was created to mark the centenary of Einstein’s annus mirabilis. It was commissioned by the Institute of Physics, which publishes Physics World, so naturally Singh’s comments piqued my interest.

Singh apparently told delegates in Amsterdam that “People hate physics, they hate ballet; all you’ve done is allowed people to hate things more efficiently. I just don’t understand how this gets vast amounts of money.” (Incidentally, Constant Speed is a dance, not a ballet; apparently there’s a difference.)

According to Times Higher Education, Singh feels the best engagement consists of “cheap, grass-roots” projects, praising YouTube video series such as Numberphile, Sixty Symbols and Computerphile, which have been watched millions of times over.

I agree with Singh that these kinds of short videos are a great example of conveying the excitement of science to lots of people for relatively little money. In fact, here at Physics World we have our own version called 100 Second Science.

But I’m not sure the two efforts can be compared. Science outreach (the YouTube videos) and art–science collaborations (Constant Speed) aren’t necessarily one and the same thing. Outreach sometimes involves art, but often it doesn’t. What’s more, good art–science collaborations aren’t just about teaching science concepts.

What Singh is right to raise, however, is the importance of ensuring that when money does get spent on public engagement of whatever type, those projects need to be properly organized, accounted for and planned. The sums involved are rarely enormous, but every penny counts and shouldn’t be wasted.

Evaluating the success of any project, however, is a hard thing to do. Is it better to get, say, 100 attendees who already have an interest in science or 50 attendees who previously had never been to a science-outreach event before? I guess it all depends on the purpose of the project.

There are many ways of measuring success but, on pure numbers alone, I’d say it’s more important that science outreach does more than just preach to the converted. That’s why I particularly enjoyed LightFest at the Library of Birmingham last month – an event to mark the International Year of Light that attracted ordinary library-goers who wouldn’t otherwise have gone to something billed as science outreach.

The bottom line, though, is how can you best quantify the success of outreach?