Entropy has been a subject of debate among physicists ever since it was formulated in classical thermodynamics some 150 years ago. One such debate centres on the so-called Gibbs paradox, in which the entropy of a system seems to depend on how much an observer knows about it. Astounding and confounding the physics community when it was first put forward by the American physicist Josiah Willard Gibbs in 1875, the paradox has since found numerous resolutions, albeit mainly in the classical setting with ideal gases.

Researchers at the University of Oxford and the University of Nottingham, UK, have now shed light on what the Gibbs paradox may look like in the quantum realm. By leveraging quantum effects, they show that more work can be extracted from a system than would be possible classically. Their result lays the theoretical groundwork for an experimental demonstration in the future, and could have applications in the burgeoning effort to manipulate large quantum systems.

The classical Gibbs paradox

The classical Gibbs paradox takes the form of a thought experiment involving a box with a partition that separates two bodies of gas. When the partition is removed, the two gas bodies mix spontaneously. To an informed observer who can distinguish the two gas bodies, the system’s entropy increases. On the other hand, for an ignorant observer who cannot discern any differences between the two gas bodies, there is no visible mixing and the entropy remains unchanged.

This difference of opinion has a physical significance since work can be extracted through the mixing process when the entropy increases. That suggests that the system’s entropy should be an objective quantity – something that does not reconcile with the existence of the different outcomes for the two observers. Gibbs, however, noted that the extraction of work depends on the experimental apparatus of the observer. Hence, the informed observer can extract work, whereas the ignorant observer has to contend with their inability to do so. This makes each observer’s reality consistent with the entropy change they witness.

Quantum effects

In the new work, the Oxford-Nottingham team considered how quantum effects such as superposition would affect the thought experiment. As in the classical case, the informed observer witnesses an entropy increase. For the ignorant observer, however, there is a marked difference after transitioning to the quantum realm. Although they are still unable to distinguish the two gases, they, too, can now witness an entropy increase. At the macroscopic limit, this entropy increase can even become as large as that which the informed observer perceives, providing the maximal discrepancy to the classical case.

Though the result might seem surprising at first, the researchers behind it say that it is a stark reminder that the classical limit is not always the same as the macroscopic one. “The classical limit is not just about large particle numbers, but also about limited degrees of control,” Benjamin Yadin, Benjamin Morris and Gerardo Adesso explain in an e-mail to Physics World. By giving the ignorant observer complex control over microscopic quantum degrees of freedom, they add, that observer becomes able to derive quantum effects at the macroscopic scale.

While some consider quantum mechanics to be a resolution to the classical Gibbs paradox, Yadin, Morris and Adesso note that their result indicates otherwise. “Our work shows that quantum effects can add an additional layer of seemingly paradoxical behaviour,” they say. They emphasise that their result is impossible in classical physics, as it relies on the symmetry requirements of bosons and fermions – a property not found in classical mechanics.

Quantum coherence turns up the heat on Maxwell’s demon

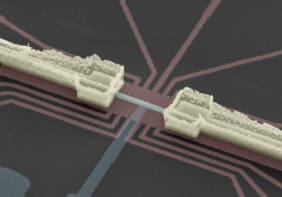

The researchers are now working on a proposal for demonstrating this effect experimentally. They explain that doing so requires a degree of quantum control, which may be possible in optical lattices and Bose-Einstein condensates. In the long term, they believe it could be possible to use this theory to build an effective quantum heat engine, one that could operate in regimes where a classical heat engine would fail.

“The question of how quantum features of identical particles may be harnessed for thermodynamical advantages is currently gaining a lot of interest – and we would like to see our work inspire other novel ideas in this area,” Yadin, Morris and Adesso conclude.

The research is reported in Nature Communications.