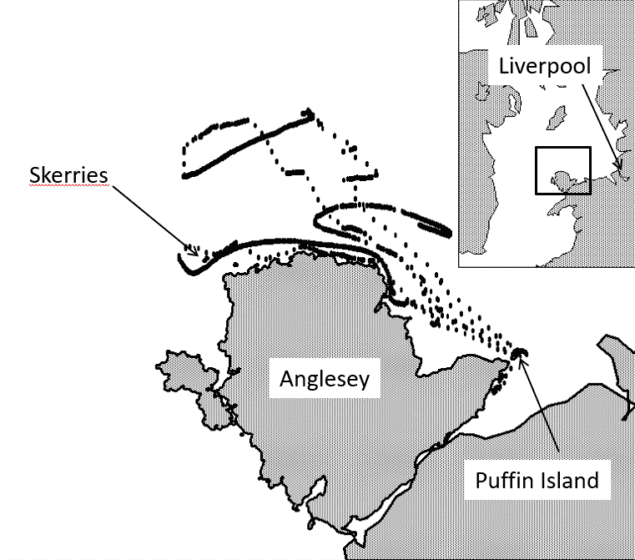

Back in 2011, the UK’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) fitted razorbills living on Puffin Island off the coast of Wales with GPS tags to study how they bred and fed. Little did the RSPB – or indeed the birds – know that the data the razorbills collected would seven years later provide details of ocean currents that could identify the best sites for generating tidal energy.

The initial study showed that at night the birds spent a lot of time resting on the sea surface. “We saw this as an opportunity to re-use the data and test if the birds might be drifting with the tidal current,” says Matt Cooper formerly of Bangor University, UK. Cooper and colleagues write in Ocean Science that “as far as we are aware, this paper is the first to describe the use of tagged seabirds for measuring currents of any kind”.

Traditionally scientists measure tides with radar or by deploying anchors and buoys fitted with scientific instruments but this is challenging and expensive. Tagged seabirds could potentially provide tidal data over a large area. The tags on the razorbills recorded their position every 100 seconds.

Razorbills come ashore only to breed; they spend most of their time at sea, foraging or resting on the ocean surface. After sunset the birds tended to float and drift. “[At these times] their changing position would reflect the movement of water at the ocean’s surface,” says Cooper.

The currents in the region of the Irish Sea that Cooper and colleagues studied have an average speed of more than 1 m/s. That’s faster than the birds can paddle but much slower than they can fly so it was easy to remove data from birds in flight. At times of low and high tide, the drifting birds changed direction as the currents moved from ebb to flow.

“We must remember that these birds are behaving naturally and we cannot determine where they go,” says Cooper. But the technique could provide tidal information over a wide area relatively cheaply, especially in remote regions. Cooper believes that the cost of generating tidal renewable energy “has been a barrier to the development of this much needed industry.”

- This article is based on a press release by the EGU