With so many different career options out there, Margaret Harris examines what university careers offices can – and cannot – do to help physics graduates find their way in the job market

It is a quiet morning in the University of Bath’s careers advisory centre, with just a few students flicking through leaflets in the reception area or browsing the small library of resources along the far wall. “We’re much busier in October and November, because that’s when many popular employers have their closing dates for vacancies,” says Diane Hay, the university’s head of careers, as she shows me into a small office nearby. “The nature of the employers working with us definitely changes as the year goes on – more small companies with specific vacancies, fewer big graduate schemes.” I notice that the room next door is reserved for the British Army; Hay explains that it is conducting mock interviews this morning. A low cadence of voices filters through the wall, and I wonder briefly if the interview – mock or otherwise – is going well.

I am here to find out what careers offices do, and what physics students can expect to gain from visiting them. This is a novel experience for me since, for a variety of reasons, I never set foot in my university’s careers-advice centre. “That’s not atypical,” says Alan Bunch, Bath’s specialist advisor for science careers. “There are lots of students we don’t see because they’re doing it on their own. But a fair proportion of them do engage with us in some way, whether it’s through careers fairs, skills sessions or a face-to-face meeting.”

The latest figures on graduate employment suggest that today’s students may need all the help they can get. In January the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) released data showing that in the third quarter of 2010 almost one in five recent graduates were unable to find work. That is better than the 27% unemployment rate for 18–20 year olds without a degree, but it is still the highest for almost a generation: the last time that new graduates faced such a harsh employment climate was in 1995, when most current students were in primary school.

Many doors

There is some reason to believe that physics graduates will fare better than the average. The ONS survey does not distinguish between degree subjects, and both government and industry leaders have for many years lamented the shortage of skilled graduates with degrees in technical subjects. Moreover, in 2009 the Council for Industry and Higher Education (a charity that links top firms and universities in an effort to boost the UK’s knowledge-based economy) predicted that demand for such graduates would grow significantly faster than the average across all subjects.

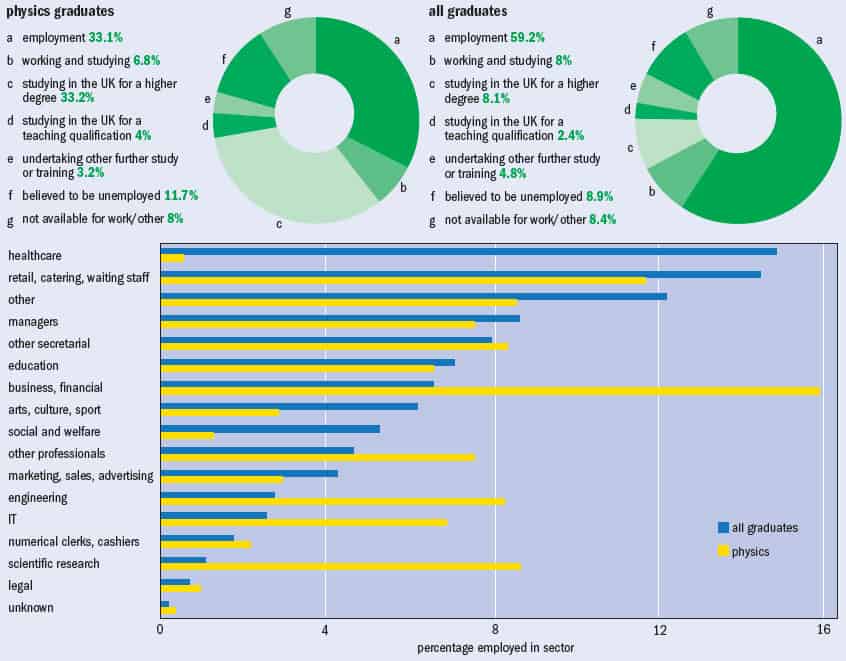

Unfortunately, that does not mean everyone with a physics degree will walk straight into a job. The most recent survey by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) found that in 2008 the unemployment rate among physics graduates six months after graduation was 11.7%, compared with an average of 8.9% across all subjects (see “What physicists do: a snapshot of graduate careers” below). That puts physics at a lowly 19th out of 27 disciplines surveyed, with physics graduates more likely to be unemployed than environmental scientists (fourth on the list, at 8.3%) and chemists (seventh, 8.7%), though slightly better off than mechanical engineers and fine-arts graduates (joint 20th at 11.8%).

These figures pose a challenge to the rosy image that many in the physics community have of the subject. We all know that in order to do well in physics, students must be bright, numerate and good at solving problems. Depending on the nature of their course, they may also acquire skills in other areas such as data analysis and computer programming. Employers value all of these things, so it is easy to conclude that a physics degree is good preparation for pretty much any career. And to some extent, the employment data support this view: according to HESA statistics, physics graduates who choose not to pursue further study (about 60% of the total) find jobs in a wide variety of sectors, including finance, engineering, information technology and medicine.

But for those who are just beginning their search for a career, such variety can be a double-edged sword. “Physics opens a lot of doors, but no main one,” says Fran Laughton, director of teaching and resources in Bath’s department of physics. “There’s no default option as there is in, say, chemistry, where the pharmaceutical industry is a major employer.”

Richard Budd, who advises physics and engineering students at Cardiff University’s careers centre, puts it in stronger terms. “Physics is often presented as a master subject, but in reality there are so many little specialized avenues you can go down that students may not be prepared for the world of work in general,” he says. “There are a very limited number of jobs out there where an ability to do quantum mechanics is actually needed.” Because of this, Budd says, physics students often need help to articulate exactly what skills they can offer employers.

Getting ahead

When I asked careers officers what physics students should do to make themselves more attractive to employers, their answer was unanimous: find a placement, internship or some other form of work experience (see “A head start: work placements” below). With a few exceptions, though, work placements are aimed at first- and second-year students. Suppose you are already in your final year, I ask Hay, or you have missed the deadlines for a placement this summer. What can the careers office do for you then?

The answer, it seems, is “plenty”. For students who already know what they want to do, the careers centre is a good place to get help with the technical aspects of job-hunting, such as putting together a CV or writing a personal statement for a postgraduate course. Some students also request help with finding jobs in a particular geographic area, says Penny Law, a careers advisor at the University of St Andrews. This is particularly important for postgraduates, she adds, because they are more likely to have spouses and children.

Many careers offices also provide training on how to take standardized tests, which play a prominent role in the recruitment process for companies such as Deloitte, IBM and Rolls-Royce that take on large numbers of graduates each year. According to Hay, 60% of these high-profile companies use basic verbal and numerical-reasoning tests to weed out unsuitable applicants at an early stage. Some also require would-be employees to complete “in-tray” exercises that measure efficiency. Although such tests only require the ability to read graphs and charts, and to interpret paragraphs of text, physics students can still struggle with them because the time allowed for each question is very short. By taking practice tests in the careers office, students can get feedback on their performance and useful time-management tips, as well as a confidence boost from knowing what to expect in a real test.

Generating ideas

This is all well and good, I say to Bath’s information-services manager, Anna Baildon, but what about physics students whose career plans are less clear – or, in some cases, non_existent? “The people who need us most are those who don’t have a clue, yet they may be the most intimidated about visiting a careers office,” she replies. Partly for this reason, careers officers usually advise students to begin their job search by looking at online resources, either the university’s careers pages or at Prospects (prospects.ac.uk) – a sprawling site that bills itself as “the UK’s official graduate careers website”.

Intrigued, I check out the Prospects site for myself. After half an hour of browsing, my impression is that its lists of careers and job titles are a decent starting point. Unfortunately, its suggestions for physics graduates are fairly unimaginative: the first two options are “research scientist” and “lecturer”, although “patent agent” and “technical author” do crop up further down the page.

When I asked careers advisors where physics students could find alternative suggestions, a few suggested the Institute of Physics’ website. Several also recommended looking at university-specific data on where physics graduates find employment. Such data are collected every year in surveys sent out to all new graduates (they are the basis of HESA’s statistics), and they offer students very specific information on where people like them have found work.

For example, the 2009 list for the University of Bath’s physics graduates includes a smattering of engineers, a radio-frequency technician and two employees at the Sellafield nuclear plant – plus someone working behind the bar at Vodka Revolutions. (They were in good company: among UK physics graduates who sought employment that year, 11.6% ended up working as “retail, catering, waiting and bar staff” six months after graduation, according to HESA.) Although few universities have followed Bath’s lead in posting such data online, the lists are generally available in careers offices.

What happens if none of these jobs sound appealing, or if students are not sure what would suit them best? At this point, the approaches of different careers centres begin to diverge. A few, like the one at Bath, seem prepared to offer fairly in-depth counselling aimed at finding out where a student’s strengths lie, what their work style is, and how their values may influence their career choices. Some students, for example, decide not to work for defence companies, Hay explains, or to focus on careers in the public sector. Other centres, such as the one at St Andrews, have compiled extensive lists of computer-based psychometric or “career match” tests. Both approaches are meant to get students thinking about broader work-related issues, in the hope that this will help them refine their choice of career.

What not to expect

One thing that all centres seem have in common, though, is a reluctance to tell students what they should do. “We aim to help students learn how to decide, not to make the decision for them,” Hay says. For some students, this “hands-off” approach can be frustrating. “I came away loaded with magazines, leaflets, help guides – they were very generous in that way,” says Nicky Guttridge, a third-year astrophysics student at University College London who agreed to visit her careers centre and send her impressions to Physics World. “But the advisor I spoke to mainly tried to steer me towards describing my perfect job, then visualizing how to get there. It seemed a bit vague…It was very much a ‘how to choose’ session, which may be helpful for many people but not for me.”

A few decades ago it was common for advisors to sit a student down, talk briefly about their interests, and then tell them what career to pursue. That is now extremely rare at university level, Hay says, largely because “people hated it, and it wasn’t very useful”. After trying out one online “career profiling” test that suggested I would make a great funeral director or security guard, I am inclined to agree. Yet if a student really wants advice, why not provide it?

“Some students think that we have a crystal ball and we can tell them what to do,” replies Julie Callaghan, an advisor at the University of Nottingham. “But the fact is that we don’t really know them. We see them only for a brief period, and it’s not possible for us to say what’s best for them.” There are also limitations on how detailed the advice can be if students are interested in specialized, technical roles. Few careers advisors have a physics background, Law observes, so they may refer such queries either to someone in the physics department or to alumni who have agreed to act as contacts in particular sectors.

The bottom line is that careers offices do not have all the answers, and anyone who visits one expecting a “quick fix” will be disappointed. Ultimately, students have to take it upon themselves to engage with the information, and to put in the hard work necessary to find a career that suits them. Still, says Baildon, there is no limit to the assistance on offer, and it is never too late to get started. “We sometimes get people turning up in their caps and gowns, fresh from graduation ceremonies,” she says. “We always do what we can to help them.”

A head start: work placements

It is perennial problem: to get a job, you need experience; but in order to get experience, you need to get a job. Or do you? In recent years, work placements have become an increasingly common way for students to pick up valuable, CV-boosting experience before they leave university, while also learning more about a career that interests them (and, often, getting paid for it). Unsurprisingly, the careers officers I spoke to were big fans. “At the moment, getting a placement is definitely the best way to make yourself more employable,” says Julie Callaghan, an advisor at the University of Nottingham. Fran Laughton, from the University of Bath, agrees. “No placement student at Bath has ever come back saying they’ve regretted the experience,” she says, adding that those who do them frequently feel more motivated about their coursework after they return. Cardiff University’s Richard Budd was also unreservedly enthusiastic about placements. “It’s all about opening up people’s eyes to new possibilities,” he says.

Placements vary in length from summer internships lasting a few weeks to year-long stints that allow students to become fully integrated into a company. The most common time to do them is between the second and third year of a university course, although some firms do accept first-year students. As with the search for permanent jobs, it definitely pays to apply early; closing dates for placements vary widely, but late-autumn deadlines are common.

Most careers offices keep information about placements to hand, but the Institute of Physics (which publishes Physics World) has recently produced a guide (Work Placements) that is aimed specifically at students who are interested in physics-based placements. Companies listed in the guide include the nuclear-services firm Babcock International, energy firms such as BP, Centrica, EDF and E.ON, and technology companies such as Thermo Fisher Scientific and IBM. Members of the Institute can access the guide via http://bit.ly/dJp4jU.