Smart speakers that can register our everyday commands have become commonplace in homes around the world. While the acoustics sensors inside these devices are far flung from the first microphone, the technology is still evolving, as Pip Knight explains

“Alexa, play some Christmas music.” “OK Google, turn on the fairy lights.” “Hey Siri, how long do you need to cook a turkey?”

This festive season, we’ll undoubtedly be chatting to our smart speakers like they’re another member of the family, and every time, the disembodied response will be almost instantaneous.

These devices – which include Amazon’s Echo, Google’s Nest and Apple’s Homepod – have already become an extra presence in more than a fifth of UK households. Indeed, in 2019 almost 147 million units were sold globally and sales for 2020 are expected to be 10% higher still. Quite simply, smart speakers have reached an astonishing level of capability for recognizing what we say. Although speculation remains as to exactly how much they are listening to and what the collected data are used for, there is no doubt that the voice-recognition technology is amazing in its accuracy. This comes down to ultrasensitive acoustic sensors and sophisticated machine-learning algorithms interpreting speech (see box “From speech to text”).

While good enough to have made it into our homes, the development of sensors for voice recognition is by no means finished. It’s not clear which technology has the most promise, and novel ideas are frequently gaining commercial attention. It also seems likely that this field, like so many others, will be altered in light of the coronavirus pandemic, with wearable sensors that can detect speech through vibrations of the throat potentially providing important diagnostic tools for diseases, such as COVID-19, that can that affect the vocal cords.

From speech to text

To generate text from live speech, two things need to happen: an acoustic sensor has to convert the incoming sound waves into an electrical signal, and then software must be used to figure out what words have been said.

For the second stage, the electrical signal is traditionally first converted from analogue to digital, before being analysed using a fast Fourier transform technique to find the variation in amplitude of different frequencies over time. Little time sections of the graphs, representing small sounds known as “phones”, are matched to the ideal short sound, or “phoneme”, that they probably represent. Then algorithms build the phonemes into full speech.

Because voices vary so much, these programmes cannot just rely on a phonetic dictionary to piece together the phonemes, which is why machine learning is so useful to improve accuracy over time. When using Alexa, for example, it will “remember” when we correct it on what we said, and so become more accurate at interpreting our individual voices. Most algorithms also use a probabilistic approach to work out which phonemes are most likely to follow each other – this is called a hidden Markov model.

A single-step approach, called “end-to-end deep learning”, is now gaining popularity and is used in current voice-recognition technology. This uses a single learning algorithm to go from the electrical signal representing audio to a text transcript without extracting the phones.

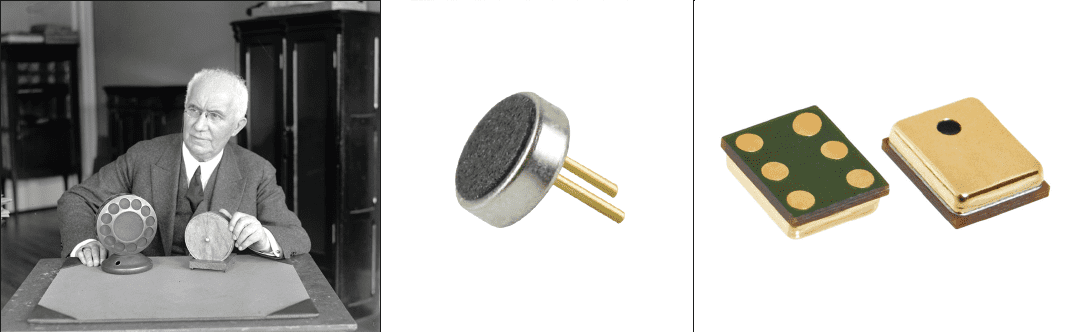

Audrey and the capacitors

The story of how acoustic sensors reached such extraordinary sensitivities begins in the late 19th century when the first acoustic sensor, the carbon or “contact” microphone, was developed independently by three inventors – Emile Berliner and Thomas Edison in the US, and David Hughes in the UK. These devices consist of carbon granules pressed between two metal contact plates with a voltage applied across the plates. Incoming sound waves cause one of the plates, the diaphragm, to vibrate. During compression, the graphite granules deform, increasing the contact area between the plates so that the resistance of the set-up drops, and current increases. These changes as the diaphragm moves mean that the sound is encoded in an electrical current.

However, it wasn’t until 1952 that voice-recognition technology was first developed. A team at Bell Telephone Laboratories (now Nokia Bell Labs) in the US created a program called “Audrey” – the Automatic Digit Recognition machine – that could understand the digits 0–9 spoken into a standard telephone (which most likely featured a carbon microphone). Audrey could be used for hands-free dialling, but had to be trained to the user’s voice and required a room full of electronics to run.

While the computing side of voice recognition has obviously come a long way since Audrey, acoustic sensors have also gone through rigorous development. Various designs, such as ribbon, dynamic and carbon microphones, have come in and out of fashion, but the one that has prevailed for voice recognition is the capacitor, or “condenser”, sensor. Originally developed in 1916 by E C Wente of Western Electric Engineering Department in the US (later becoming Bell Telephone Laboratories), the design hinges on the fact that the voltage across a capacitor depends on the distance between the plates. To this end, the sensor features a stationary backplate and a moving diaphragm, charged up by an external voltage. As the diaphragm vibrates from the incoming sound waves, the capacitance – and hence the voltage across the capacitor – varies with diaphragm displacement, from which the amplitude variation of different frequencies in time can be calculated.

The inventors Gerhard Sessler and Jim West at Bell Telephone Laboratories further developed the capacitor sensor in 1962 by using an electret diaphragm, creating the electret condenser microphone (ECM). Electret materials, such as Teflon, have a pre-existing surface charge, which means they keep a permanent voltage across the capacitor, thereby reducing the power input needed. Roughly 3–10 mm in diameter, ECMs dominated the general microphone market for nearly 50 years, but the move towards compact devices led to drops in signal-to-noise ratio and decreased stability, particularly in variable temperature environments.

When it comes to voice recognition, ECMs have therefore been mostly replaced by micro-electro-mechanical system (MEMS) capacitive microphones. At only 20–1000 μm in diameter, these devices are typically what you find in smart speakers. MEMS sensors differ from ECMs in the internal circuitry, notably in that they convert the signal from analogue to digital while still inside the microphone. Apart from being less susceptible to electrical noise than ECMs, the design is smaller and easier to make, since the silicon wafers required can be made on semiconductor-manufacturing lines. The drawback with MEMS microphones is that they are not very durable, so do not cope well with harsh environments. This is because dust particles tend to gather under the diaphragm, limiting its vibration, and rain can also damage it. Even in ambient settings, the trapped layer of air between the diaphragm and backplate makes it harder for the diaphragm to vibrate at maximum amplitude, limiting the device’s sensitivity.

A new way?

Although capacitor sensors have dominated the industry for decades, the technology might not hold all the answers for the future. US firm Vesper Technologies is paving the way in the commercial development of piezoelectric acoustic sensors, with the endorsement of Amazon Alexa. Founded in 2014, the company’s initial designs were based on the PhD research of Bobby Littrell, the company’s chief technology officer, and the work has since won many awards.

These devices work using a diaphragm made of a piezoelectric material, such as lead zirconate titanate, that directly converts the mechanical energy from sound waves into an electrical response. When the piezoelectric diaphragm stretches as a sound wave hits, the distances between ions are increased, creating small electric dipoles in the new most energetically stable ionic arrangement. The lack of a centre of symmetry in the crystal’s unit cell means no equivalent dipoles are formed on the other side of a centre of symmetry (which would cancel out, to leave no net dipole). The cumulative effect of all of these tiny dipoles across the crystal is the generation of a voltage, which varies in time as the strain in the crystal varies.

Compared with capacitor acoustic sensors, piezoelectric devices have the distinct advantage of containing just a single layer, meaning they do not trap dirt, air or rain and so are much more durable. The devices are also self-powered, meaning the range of applications, particularly when there is limited room for a battery, is much wider.

However, thin-film devices like these – and the capacitive designs – tend to be quite difficult to make. “You need a high or ultrahigh vacuum,” explains Judy Wu, a physicist at the University of Kansas in the US, “and you need to select a good substrate because [otherwise] you will not be able to get epitaxial growth.” Epitaxial growth is what happens when a thin film grows as a single crystal with one orientation of the unit cells. This is needed so that the dipoles formed under mechanical strain all point in the same direction. “You have to really raise the temperature,” Wu continues, “to give the thermal energy and the mobility when you put the atoms on the substrate [for them] to find the minimum energy position to form a perfect lattice.”

As Vesper has shown, these conditions can be produced, but they do limit the device applications. For instance, growing a thin film of a single crystal on a flexible substrate is difficult, since single crystals have to grow on an ordered structure to be ordered themselves and most flexible materials are not crystalline. “You cannot provide a perfect lattice there – it’s just amorphous material,” explains Wu.

However, Wu and her team are working on a potential solution. They have used graphene in solution to grow piezoelectric zinc oxide nanowire arrays for a strain sensor (ACS Applied Nano Materials 3 6711). As the graphene is flexible but crystalline, the nanowires grown are still piezoelectric crystals. The difficulty is that it is very delicate. The researchers overcame this by using a solution to grow the nanowires, so as not to destroy the graphene’s perfect structure with sputtering techniques, which would reduce its conductivity. Not only this, but the ambient pressure and relatively low temperature used (90 °C) mean the process is very cheap.

Their strain sensor works by detecting changes to graphene’s conductivity, which occur as a result of the extra surface charge that develops on the zinc oxide nanowire array when it is mechanically strained. Wu says they are also working on a flexible version of the sensor, encased in PET plastic. The research is still in fairly early stages, and the sensor does not have a definite application just yet, but in the hope of filling some niche function needing a sensitive, flexible sensor, they have patented the graphene process. “We want to do something the ceramic sensor cannot do,” Wu explains, “[Our sensor] might recognize your skin, or recognize your voice, because it’s very sensitive to acoustics.”

Following nature

Adding to the whirlpool of ideas in the voice-recognition field, Keon Jae Lee and his team at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) have been developing a new piezoelectric sensor design (Advanced Materials 32 1904020) that mimics human hearing. Speaking to Physics World, Lee light-heartedly explained his faith in the concept, “If nature is doing it, it’s probably the most efficient way.”

Their piezoelectric sensors have a similar shape to the basilar membrane in our ear (see box “How ears have inspired a new kind of voice-recognition device“), thereby allowing about twice as much information to be harvested than conventional capacitor sensors. This advantage comes from the fact that, rather than collecting a single signal containing all the frequencies and analysing that to figure out frequency amplitudes, many signals (in Lee’s case, seven) are analysed from various positions along the membrane. This wealth of information makes voice predictions more accurate. Lee and colleagues found their 2018 design exhibited 97.5% accuracy in speech recognition; a 75% improvement on a reference MEMS condenser microphone. “I think the two advantages are accuracy and sensitivity,” Lee concludes. “We can pick up sound from a long way away and recognize individual voices.”

The tricky part of their research is analysing the data from the channels to give the relative amplitudes of different frequencies, since amplitudes are modulated by the resonance behaviour of the channel. It’s why Lee thinks so few research groups have taken up the idea. But his group seems to have cracked it, and even founded a spin-off company manufacturing its unique sensors, Fronics, in 2016. Lee is optimistic for the future of the design commercially and believes the team has found the right number of channels for the sensor. It’s a fine balance, he explains, between improving your accuracy by collecting more data, and needing a bulky machine to process it all.

How ears have inspired a new kind of voice-recognition device

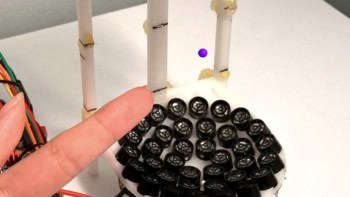

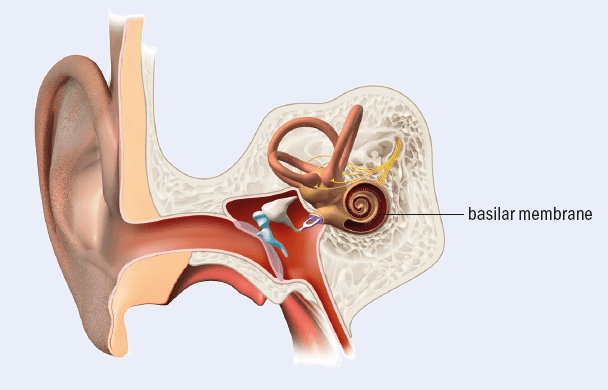

Keon Jae Lee and his team at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology are developing a new voice-recognition sensor that draws inspiration from hearing in nature. It has a piezoelectric membrane that mimics the basilar membrane found in ears, which in humans is curled into a spiral inside our cochlea. Lee’s design, however, is more similar to the straight membrane found in the ears of many birds and reptiles.

Shaped like a trapezium when viewed from above, a basilar membrane is tapered: it is narrow and thick at the base (located in the centre of the spiral in our ears) and becomes wide and thin. The membrane can be thought of as a series of oscillating strings lying perpendicular to the axis of symmetry of the trapezium, except that the strings really form a continuous spectrum that waves can pass between.

An incoming sound creates a travelling wave that passes down the membrane, beginning at the wide, thin end. Essentially a superposition of individual waves of different frequencies, as each wave travels down the membrane, it will reach one of the oscillating strings that has a resonant frequency equal to the wave’s own frequency and will vibrate most strongly here. The membrane is covered by more than 10,000 hair cells, which transmit information to the brain about the amplitude of the frequency at their position along the membrane.

Ears are more complex than this membrane alone: for example the hair cells also amplify the “correct” frequency for that position on the basilar membrane. But the concept of a collection of resonating sections of a membrane is the key to Lee’s design.

Neck sensors and COVID-19

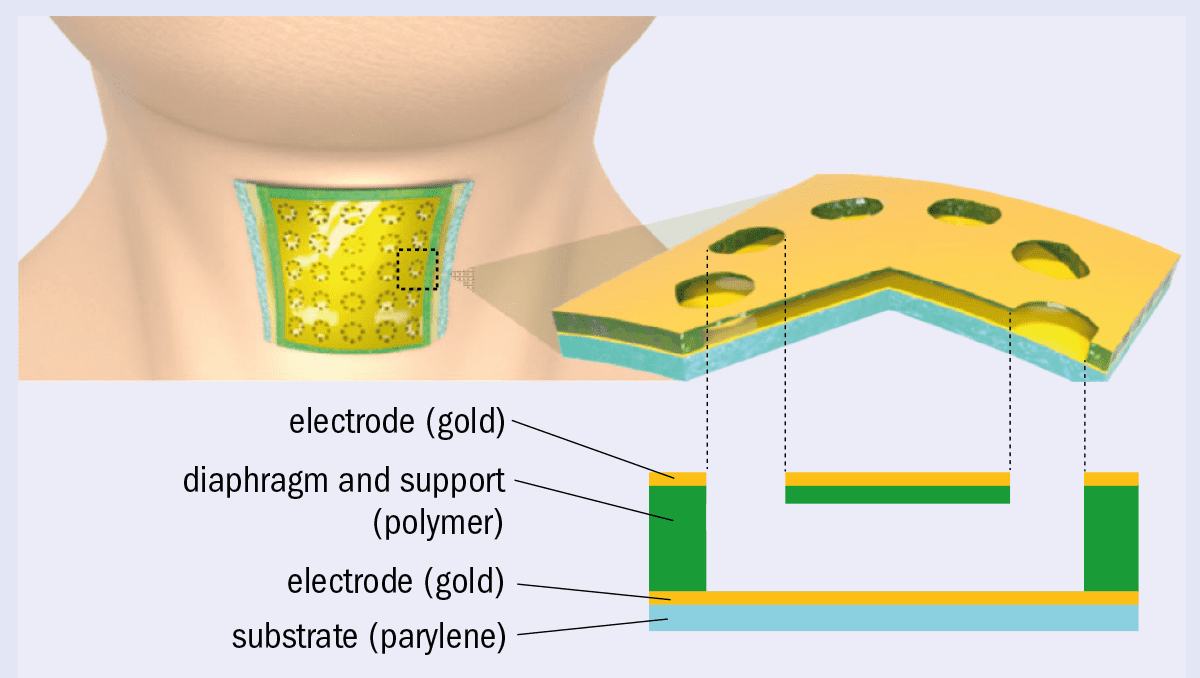

Voice-recognition technology is not limited to a device sitting in the corner of your room or in your pocket. Sensors that work using neck vibrations, instead of sound waves travelling though air, would be very useful where sound propagation is almost entirely prohibited, such as noisy industrial environments or when people have to wear bulky equipment like gas masks. A breakthrough occurred late last year when Yoonyoung Chung and his team from Pohang University of Science and Technology, South Korea, reported creating the first flexible and skin-attachable capacitor sensor, which can solve this problem by perceiving human voices through neck-skin vibrations on the cricoid cartilage (part of the larynx). Demonstrating that skin acceleration on the neck is linearly correlated with voice pressure, they realized that they could measure the variation of voice pressure in time by designing a device that detects skin acceleration through changes in capacitance (Nature Communications 10 2468).

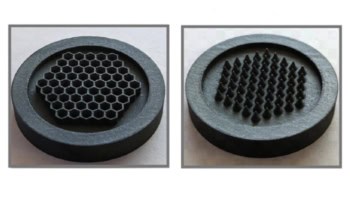

The sensor Chung’s team has created is less than 5 μm thick and the diaphragm is made from epoxy resin (figure 1). “We wanted to develop a flexible microphone sensor, so it was natural for us to use a polymeric material, which is intrinsically flexible,” explains Chung. The individual sensor panels are small enough that any neck curvature is negligible in them and will not affect vibrations – a bit like how the Earth’s curvature seems small enough to ignore from our perspective, since we occupy such a small proportion of its surface.

What’s also vital for capacitive sensors is that they have a “flat frequency” response. This means that no frequencies appear falsely high in amplitude because of a resonance in the device, and it makes electrical signals much easier to analyse. In order to achieve this, the diaphragm must have a narrow resonance peak that lies well above the frequency range of the human voice. Chung achieved the narrow width by making the diaphragm from a fully cross-linked epoxy resin with a low damping ratio. Cross-linking prevents the movement of molecules past each other and the oscillation and conformational flip of the phenyl rings, which would all lead to friction between molecules. The second condition, a high resonant frequency, could be achieved by either a high stiffness or a low mass. The snag is that a device that’s less stiff is actually more sensitive because the diaphragm’s vibrations are bigger. Chung has found a solution to this stiffness dilemma: instead of reducing the stiffness of the bulk material, he added holes to the diaphragm. The holes reduce the diaphragm’s mass to satisfy the high resonant frequency, while keeping stiffness low to increase sensitivity. “This solution has also been commonly used in the silicon MEMS area in order to reduce the air resistance,” adds Chung.

The group has submitted patent applications for the design and is collaborating with several industry partners, though Chung is careful to note that commercialization is still in the early stages, since there is more research to be done in the lab. “We are now trying to make a sensor interface circuit on a flexible substrate so the entire sensory system can be attached on the neck skin without any difficulties,” he explains. The current design has a rigid circuit board, which can cause occasional problems by suppressing neck vibrations.

Throat sensors like these could also be used to diagnose illnesses like COVID-19, which have symptoms that manifest themselves in the vocal cords. Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US have found that COVID-19 changes our voice signals by affecting the complexity of movement of the muscles in the throat (IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology 1 203). They hypothesized this to be due to an increased coupling between muscles, preventing them from moving independently. Sensor devices paired with an app could provide early-stage screening to alert people to seek further testing for COVID-19. “It can also be used as a cough detector to diagnose people,” speculates Chung, while considering clinical uses for sensors like his. Even Vesper, though its current designs are not flexible, has shown interest in this potential outlet for innovation. “Our team is already brainstorming new ideas such as acoustic respiratory health monitors,” wrote its chief executive Matt Crowley in a blog post in March about the pandemic.

An advantage of sensors being repurposed from a voice-recognition context is that there is money available for developing the technology. Well-resourced tech companies are always on the lookout for technology that has exciting prospects for smart devices – such as sensors like Lee’s and Chung’s, which are sensitive enough to recognize individual voices in lieu of a password or fingerprint. And given the human need, as a result of the pandemic, to quickly detect respiratory illnesses on a mass scale, throat-monitoring devices will likely be on a fast-track to becoming a viable diagnostic technology. It will be interesting to see how both of these areas of innovation evolve over the next few years following the pandemic. Likewise, the debate between capacitive and piezoelectric sensors will continue to change, possibly as a result of manufacturing improvements, or the changing demand for certain features, like flexibility and resistance to harsh environments. Perhaps, one crisp December morning as you wait for the Brussels sprouts to boil, you might ask your smart speaker for an update.