By Margaret Harris

Giving out science careers advice is tricky. On the one hand, you want to be encouraging – not least because if you aren’t, there is a chance that your advisee will go on to win a Nobel prize, and you will then look extremely silly. But on the other hand, you also want to prepare the person, mentally, for the possibility of failure. Otherwise, when they do fall short, they may not know how to recover and try again.

The need for balance between encouraging big dreams and preparing for failure was one of the central insights to come out of Sunday’s panel on “Feminism, sexism and bringing up girls” at the Cheltenham Science Festival. After one of the panel members, psychologist Tanya Byron, noted that in clinical practice she sees many bright, successful girls whose fear of failure is “absolutely destroying them”, her fellow panellist Gabriel Weston put her finger on the heart of the problem. How, Weston asked, do we celebrate young women’s achievements and encourage their dreams without also pushing them to be “perfect little glass statues” who shatter under pressure?

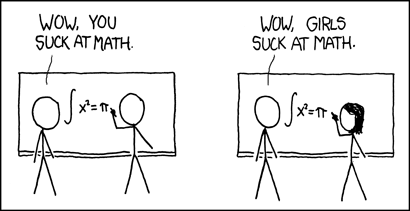

At this point, I was hoping that the panel – which also included the feminist campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez and a journalist, Tanith Carey – would go on to talk about how this fear of failure shapes the experience of girls and women in science. But while Criado-Perez briefly mentioned studies showing that women do worse on mathematics tests when they are exposed to “women are bad at maths” stereotypes, the session ended before anyone could dig into this more deeply. And that’s a pity, because there are some interesting things that can be said about failure and physics.

In physics, failure and success are pretty clear-cut. On physics exams, especially, an answer is usually either right or wrong. Most people who choose to study physics are okay with this (indeed, some find the clarity appealing), but that is partly because they are usually “high fliers”, accustomed to getting top marks. The clear-cut nature of success in physics exams has, basically, reinforced their sense of themselves as successful people.

At some point, though, no matter how much of a high flier you are, you will fail. And as a professional physicist, you will fail pretty much all the time. Your experiments won’t work. Your ideas will go nowhere. Sooner or later, your theories will be disproved by observations. To be a successful physicist, then, you need to do failure well. The playwright Samuel Beckett put it nicely: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

These things aren’t just true for girls, of course. But if high-achieving girls are less able than boys to cope with unaccustomed failure – whether because they’re pushed to be “perfect glass statues”, or because when a woman fails in a male-dominated field, it’s regarded as evidence of a wider deficiency in womankind – then that could, in part, be why the percentage of women in physics remains dismally low, even at the early stages of the pipeline.